Before the departmentalization of Princeton University’s Center for African American Studies in 2015, a colleague asked Eddie S. Glaude Jr. — the current chair of Princeton’s Department of African American Studies (AAS) — a question.

“What’s the big idea in African American Studies?”

Glaude responded, reflecting his belief in the deep-rooted value of African American Studies, “What’s the big idea in English?”

In an event hosted Wednesday by the Clayman Institute for Gender Research, Glaude, along with fellow panelists and experts in the field of African and African American Studies (AAAS), discussed what they consider the urgent need to departmentalize AAAS at Stanford.

In the past months, more than 5,000 people have signed a petition organized by the Black Student Union (BSU) and Black Graduate Student Association (BGSA) to departmentalize Stanford’s AAAS program. Numerous Daily op-eds and The Daily’s editorial board have called for departmentalization. University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne wrote in a June 30 open letter that along with introducing new initiatives aimed at addressing racial injustice, Stanford will consider the departmentalization of AAAS.

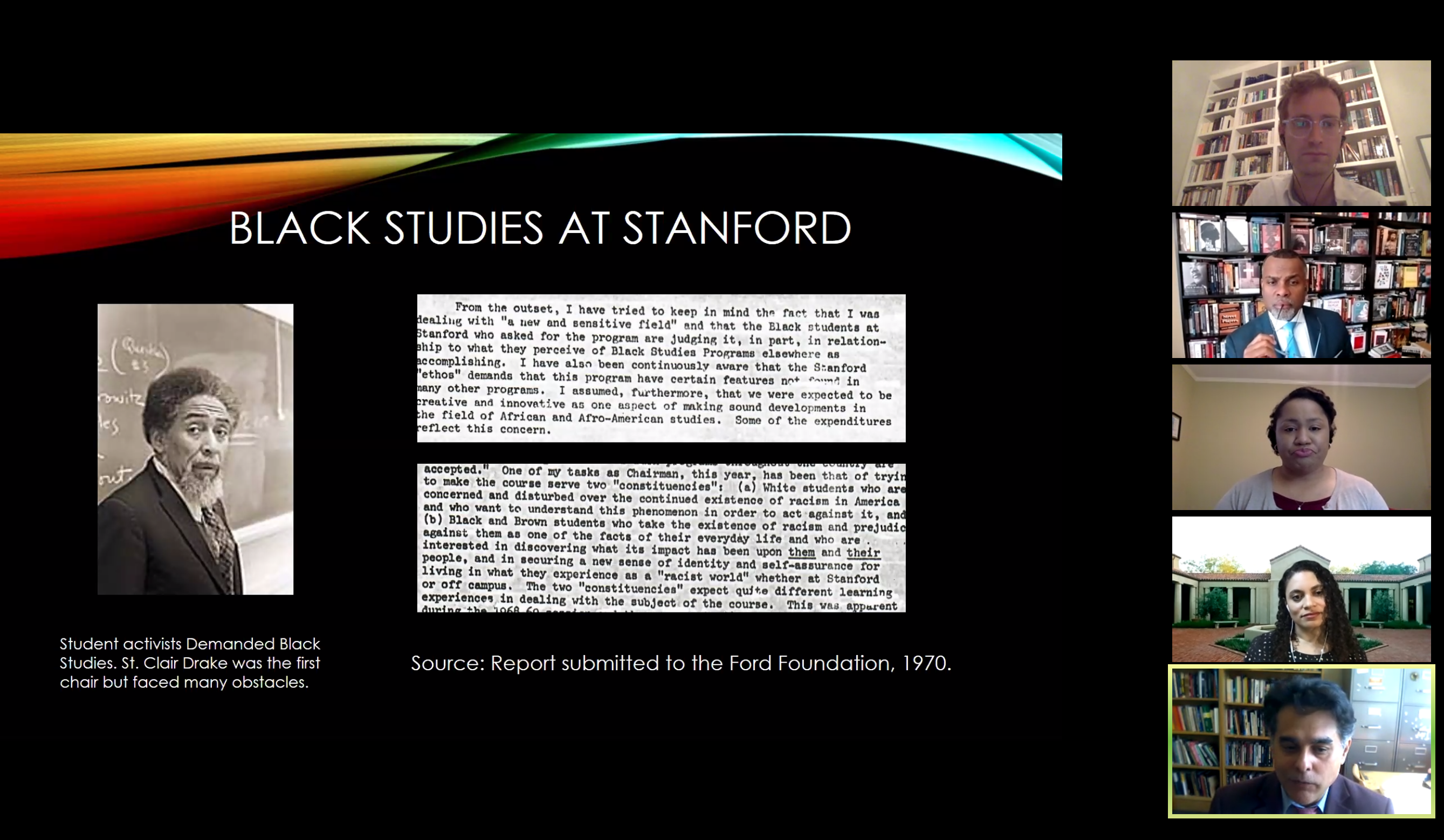

Fabio Rojas, a sociology professor at Indiana University, Bloomington, kicked off the panelists’ discussion, talking about the birth of AAAS in 1966 at San Francisco State University (SFSU).

Jimmy Garrett, an SFSU student and Black Panther Party member, “generated the idea of Black Studies as a coherent set of courses,” developing his own curriculum through SFSU’s experimental college, according to Rojas.

Rojas pointed to Harvard’s AAAS program as a model for Stanford — to successfully departmentalize, Rojas found the importance of “recruiting people with strong bureaucratic skills, finding internal allies, finding external sources of funding and preparing for the ups and downs of enrollment.”

Glaude discussed Princeton’s trajectory toward departmentalization, citing the volatile nature of Princeton’s AAS program over time.

Princeton went from having “one of the best programs in AAS” to being left with only one professor, Glaude said. He explained that, because the AAS program was not a department — and therefore did not have hiring abilities — it could not rebuild.

“Departmentalization would allow AAAS to react to market changes and recreate itself,” no longer reliant on other programs or departments to maintain its scholarship, according to Glaude.

Stanford AAAS Fellow Aileen K. Robinson added that, because programs have no hiring power and lack the ability to tenure, joint-hiring leaves faculty members “indebted to colleagues in different programs,” and thus “stunts our growth in scholarship.”

Beyond the benefits gained from departmentalization, including the ability to hire and grant tenure, the panelists also describe departmentalization as being a tool for granting institutional legitimacy.

“Departments are a way a university institutionalizes knowledge,” Rojas said. “It’s how they show what is useful and what is not.” In keeping AAAS relegated to program status, Rojas said, Stanford reveals its belief that the “knowledge is not worth the investment.”

Glaude compared AAAS to neuroscience, which also emerged from interdisciplinary studies.

“A problem, like the brain, can drive interdisciplinary work. From there, a new field emerges. A university must respond to that,” Glaude said. “Although neuroscience looks like a department now, it still functions in an interdisciplinary manner.”

Glaude said that AAAS should be looked at equivalently. Although its roots are interdisciplinary, its core is connected to the African and African American struggle. Africana philosophy, Black literature and African American religions are all rooted in this struggle. Departmentalization facilitates analysis of these nuances, and allows for academics to “track these changing conversations over time and space.”

Robinson described the longevity created by departmentalization as essential for scholars looking to do research and become more involved in the discipline.

Despite the value of departmentalization, Kimberly Thomas McNair, postdoctoral fellow of AAAS at Stanford, acknowledged obstacles that Stanford might face if it chose to pursue departmentalization.

“Historically, African American Studies comes from community demands, not from bureaucracies and institutions deciding its value,” McNair said. “The push toward professionalization can leave certain experts out, as they don’t have credentials traditionally recognized by institutions.”

Further, McNair posed, “Do we seek validation from our community or academia?”

Ultimately, McNair and her fellow panelists acknowledged that departmentalization should not be an act of charity on the part of the University.

Glaude said he sees no reason why Stanford cannot departmentalize its AAAS program, especially after watching Princeton, a university he described as being traditionally conservative, do the same.

The event was hosted and moderated by Adrian Daub, director of the Clayman Institute for Gender Research. Daub acknowledged the Clayman Institute’s support of departmentalization, stating that Black lives are a “central feminist issue” and that Stanford’s administration cannot claim to value Black lives without departmentalizing AAAS.

The event was concluded by Jameelah Morris and Casey Patterson, Stanford graduate students advocating for the departmentalization of AAAS. Morris and Patterson promoted their petition for the departmentalization of AAAS, as well as a Google form for students and faculty interested in getting involved.

Contact Nina Iskandarsjach at ninaisk ‘at’ stanford.edu.