Stanford released a draft Title IX policy on Tuesday morning, giving the campus community six days to provide comment and feedback on its new procedures — which also have to comply with controversial federal rules — for adjudicating cases involving sexual violence on campus.

Ahead of the 5 p.m. deadline on Sunday for submitting a comment, members of the ASSU Committee on Sexual Violence Prevention, who had been meeting with the University drafting committee regularly since spring quarter, worked quickly to organize outreach on their major criticisms of the Title IX policy implementation. They believe Stanford’s draft policy contributes to creating a dangerous and hostile environment for survivors of sexual assault on campus.

“Last week [the administration] sprung on us that of our 25 recommendations, they were only taking two of them — one of which is mandated by California law,” said Maia Brockbank ’21, ASSU co-director of sexual violence & relationship abuse prevention, in a teach-in the night after the draft policy was released. “So basically out of all of this time we’ve devoted to meeting with them, it was all just lip service.”

The University did not immediately respond to a request for comment about why it did not implement a majority of the recommendations, but Provost Persis Drell wrote in a press release that “Stanford’s draft Title IX Process is the result of a collective effort of many individuals at the university,” after taking in input from the Faculty and ASSU advisory boards. Drell also said that the University wished it could have offered a longer comment period, but was limited by a federal deadline of Aug. 14 to draft new Title IX policies.

Despite timeline restrictions, in less than five days, a Sexual Violence Free Stanford petition calling for the drafting committee to implement the rest of the ASSU recommendations has amassed over 1,000 signatures. In that same amount of time, the Sexual Violence Free Stanford Instagram page has garnered nearly 650 followers.

The University has said that while they “expect that many thoughtful individuals within the Stanford community will not agree with some of the requirements of the federal regulations, they are set by law and cannot be altered.”

But ASSU committee members believe that the University has “complete power” to follow these recommendations, since they do not contradict federal rules. Brockbank said in the teach-in that education department secretary Betsy DeVos’s proposed regulations were already “horrible” — the ASSU’s goal in compiling recommendations for the drafting committee was to present ways to implement those rules “in a way that is as least harmful as possible to the Stanford community, specifically with an eye towards survivors.”

With the last-minute communication that a majority of the recommendations wouldn’t be taken, Brockbank said, “We’re feeling betrayed by the way that this process has been done.”

Providing more legal aid

The new federal rules that Stanford must adhere to will make the hearing process even more grueling and traumatizing for survivors, Brockbank said in the teach-in. She expects fewer people to want to go through the hearing process. Few people already do; only five hearings took place out of 300 reported cases in the 2018-2019 year.

Stanford’s new policy provides only two hours of pro-bono legal aid before a hearing (after which they will pay a flat fee to attorneys). Only offering two hours pre-hearing — when most cases don’t ever go to a hearing —means that for most people, the only pro-bono legal aid they will have access to throughout their Title IX process is those two hours, Brockbank said.

“Wealth should not be the determining factor in whether or not you can get justice after being assaulted,” Brockbank said.

The draft policy does include the addition of a new “process navigator,” who will be available to both complainants and respondents free-of-charge to help advise them through the convoluted Title IX process. Process navigators are not complete replacement for attorneys: They cannot advise or advocate on behalf of individuals in a legal capacity, they are employees of the University and they are not bound to confidentiality laws and may be asked to disclose information in legal proceedings.

The lack of legal aid is only complicated by the fact that parties must choose from a list of lawyers that Stanford has compiled, which puts into question their position as objective, third-party advocates for the students, Brockbank said.

Most notably, Stanford cut its ties with lawyer Crystal Riggins after she spoke out against the Title IX process in a 2016 New York Times article. Riggins was the only lawyer at the time on the University-identified attorneys list who specialized in representing student complainants (as opposed to respondents). The reason senior associate vice provost Lauren Schoenthaler gave then for dropping the lawyer was that Riggins showed “a lack of faith” that was “disappointing,” and it “does not make sense for the University to continue to refer our students to you.”

Student cases were previously heard by a trained in-house panel (selected from a pool consisting of faculty, staff and graduate students appointed by the Provost). The new draft policy, however, indicates that external judges without any “current” Stanford affiliation will serve as hearing and appeals officers. But it’s not clear who exactly this includes; Julia Paris ’21, who along with Brockbank and Krithika Iyer ’21 serves as ASSU co-director of sexual violence & relationship abuse prevention, said in the teach-in that the ASSU committee explicitly proposed excluding Stanford alumni, donors and parents from serving as hearing and appeals officers.

“So it’s not that they didn’t think of these; it’s a clear omission,” Brockbank added.

Timeline

The federal standard for the length of Title IX investigations has been 60 days, per the Office for Civil Rights’ Obama-era “Dear Colleague” letter — though that expectation was not binding and allowed for some cases to take longer to investigate depending on their complexity. There is “no fixed time frame under which a school must complete a Title IX investigation” under new federal guidance, allowing schools to decide the time frame.

Stanford has utilized that flexibility to define a time frame of 120 days, from receipt of the complaint to completion of a Title IX investigation. They also add that while they will “strive to complete this … procedure in a prompt manner,” they will “not compromise a thorough and fair process” in order to meet that deadline, either.

The ASSU committee is pushing for Stanford to restore the 60-day timeline so that complainants can “know … that there is some kind of restriction in terms of how long the burden of the re-traumatization will last,” Brockbank said.

Clery definitions

Advocates for survivors of sexual assault have also pointed to subtleties in definitions delineated in the draft Title IX policy that the ASSU committee says place undue burden on complainants.

Particularly for the definitions of sodomy, sexual assault with an object and fondling, Stanford’s draft policy not only denotes different requirements of consent than does the Clery Act (a federal statute that requires colleges to disclose information about crime on campuses), but also separates those instances from the rape definition.

The Clery Act only requires victims of sodomy, sexual assault with an object and/or fondling to prove a lack of affirmative consent, meaning that silence — since it is not affirmative — does not indicate consent: Under Clery, the acts are considered misconduct when they are perpetrated “without the consent of the victim,” including when the victim is incapable of giving consent because of age or mental incapacity.

Stanford’s description of the acts are similar to Clery descriptions, but differs in that it requires that the conduct was perpetrated “forcibly” or “against that person’s will.” The ASSU committee interprets this to mean that silence may equal consent for these cases.

The ASSU committee believes that, under these requirements, victims of sodomy, fondling and sexual assault will be subjected to an “unnecessarily and arbitrarily high bar” (compared to having to prove rape under Title IX), despite the fact that both the Clery Act and California law mandate affirmative consent standards.

“In other words … silence is enough to [constitute] rape, but is not enough to prove fondling, sodomy or sexual assault with an object,” said fourth-year sociology Ph.D. student and ASSU advisory board member Emma Tsurkov during the teach-in. She added that the inconsistency “makes no sense,” particularly because there is overlap between the legal definitions of rape and sodomy.

The Clery Act has explicitly revised the definition of rape to include sodomy and sexual assault with an object. Sodomy, though now a gender-neutral offense, has been historically used to target “unnatural” acts including anal and oral sex (which are already covered under rape) between homosexual couples. Charges were rarely levied against couples of the same sex.

In cases where the definitions of rape and sodomy overlap, the Title IX investigator decides which charge to use. Activists’ concern is whether those charging decisions could be made in a way that ends up having a disparate outcome on the queer community.

“By first of all labeling their experiences not as rape, and also holding them to a higher bar,” Tsurkov worries about disproportionately hurting a group that is already marginalized in general on campus, but also specifically in the space of sexual violence.

“These are the types of tiny changes in language that seem like it wouldn’t matter,” said Annabel Conger ’21, and yet they do, “especially when it comes down to legal applications.”

“It just seems like something that will likely end up disproportionately affecting the queer community,” they added.

Cross-examination

Obama-era “Dear Colleague” guidelines discouraged colleges from allowing parties to cross-examine each other personally, citing concerns that “allowing an alleged perpetrator to question an alleged victim directly may be traumatic or intimidating.” Studies, personal anecdotes and experts agree that survivors often find the idea of cross-examination to be invasive and traumatizing, which may deter reporting even further.

New regulations also do not allow in-person cross examination; however, they do require cross-examination through a “support person,” such a relative, friend or an attorney, with federal rules arguing that cross-examination is pertinent in fact-finding and in allowing the accused to identify inconsistencies in the complaint.

Per federal rules, Stanford must institute cross-examination. However, like others have suggested, the ASSU recommends that Stanford establish a system requiring parties to submit questions to the hearing officer for approval before cross-examination begins, so that victims do not have to be subject to questions that are, as Tsurkov described in the teach-in, “harassing, belittling, undermining, humiliating and so on.”

Even if the hearing officer decides during the cross-examination that a victim does not have to respond to a question because it is inadmissible, the question has still been asked, which can itself be distressing and traumatizing.

“It’s like saying, ‘Don’t think of an elephant,’” Tsurkov said. “Well, now you’re already thinking about it.”

Conferences

New federal rules mandate that Stanford narrow its Title IX jurisdiction to conduct that occurs on-campus or off-campus at a school-sanctioned program or activity. The ASSU committee recommends that Stanford explicitly declare academic and professional conferences under their

“programs and activities” for the purposes of Title IX.

“A lot of the sexual harassment and assault that graduate students experience … happens specifically at conferences,” because it’s a place where students are “isolated with members of faculty,” Tsurkov said.

A Stanford campus climate survey showed that graduate students were more likely than undergraduates or co-terms to experience faculty harassment in particular. Many female academics responded in a a Twitter thread last year with their experiences of sexual harassment and assault at academic conferences they’d attended.

“I’m looking to apply to graduate school, and Stanford is a place I’m considering,” Conger said. But they added that decisions like that could change their calculus for wanting to go to Stanford for graduate school.

Expulsion for egregious offenses

The ASSU recommendation and petition calls for Stanford to make expulsion the mandatory sanction for the most serious offenses of sexual assault (penetration through force or unconsciousness); while this is the “expected” outcome, the ASSU committee notes that this rarely happens in practice.

Only two students have been expelled for sexual assault in the last two decades, despite investigations finding more than that number responsible for offenses that meet the threshold for the sanction of expulsion.

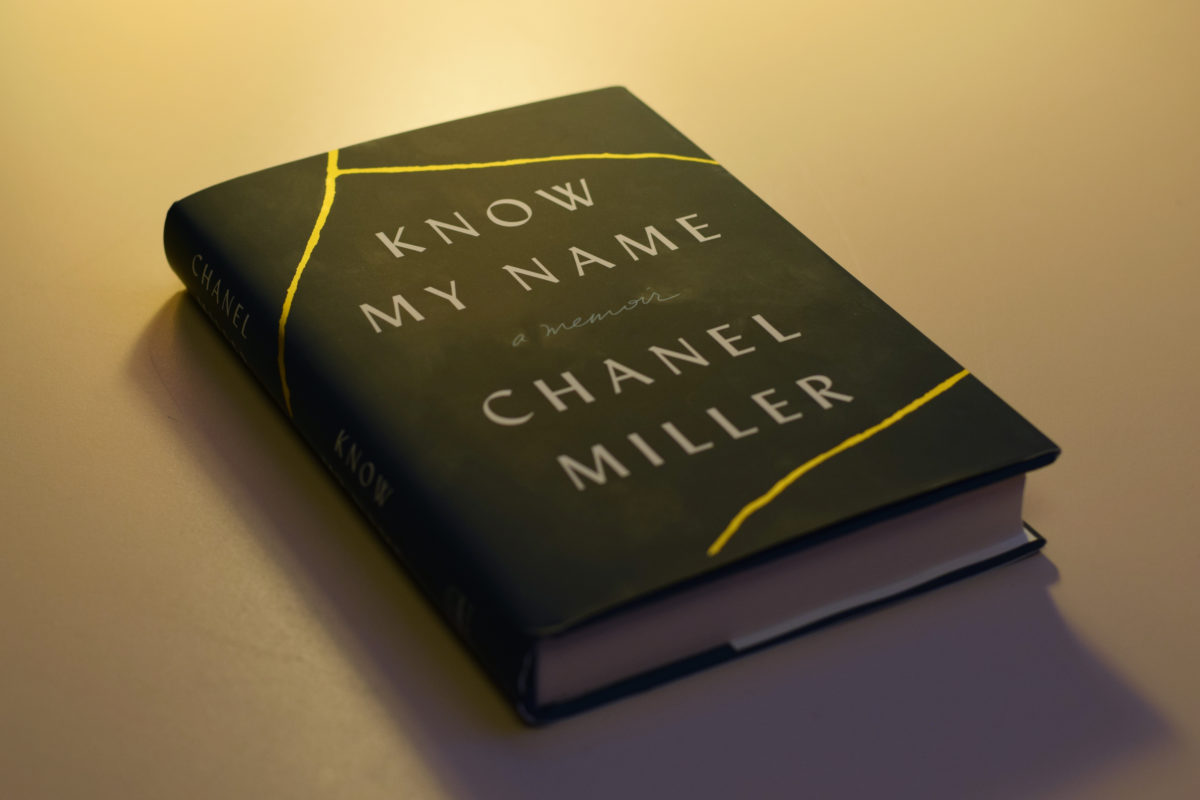

One student who was expelled was allowed to receive his degree for prior units earned. Another was granted a three-quarter suspension, even though his offense met the threshold for expulsion. Three others, including Brock Turner, were allowed to decide to leave the University without the ability to re-enroll.

Former Provost John W. Etchemendy Ph.D. ’82 explained to The New York Times in 2016 why Stanford’s Title IX process at the time included significant protections against expulsions: “Imagine a senior, who has paid four years of Stanford tuition,” he said. “Being expelled is really a life-changing punishment … I think we as an institution have a duty to take that very seriously.”

“I don’t think people walk around on campus contemplating rape,” Sinéad Talley ’18, who was sexually assaulted on campus, told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2018. Her assaulter was granted a two-quarter suspension. “But in the moment, if they thought they could lose their place at Stanford — that they could get expelled — I think that could have a deterring effect.”

Lexi Kupor contributed to reporting.

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.