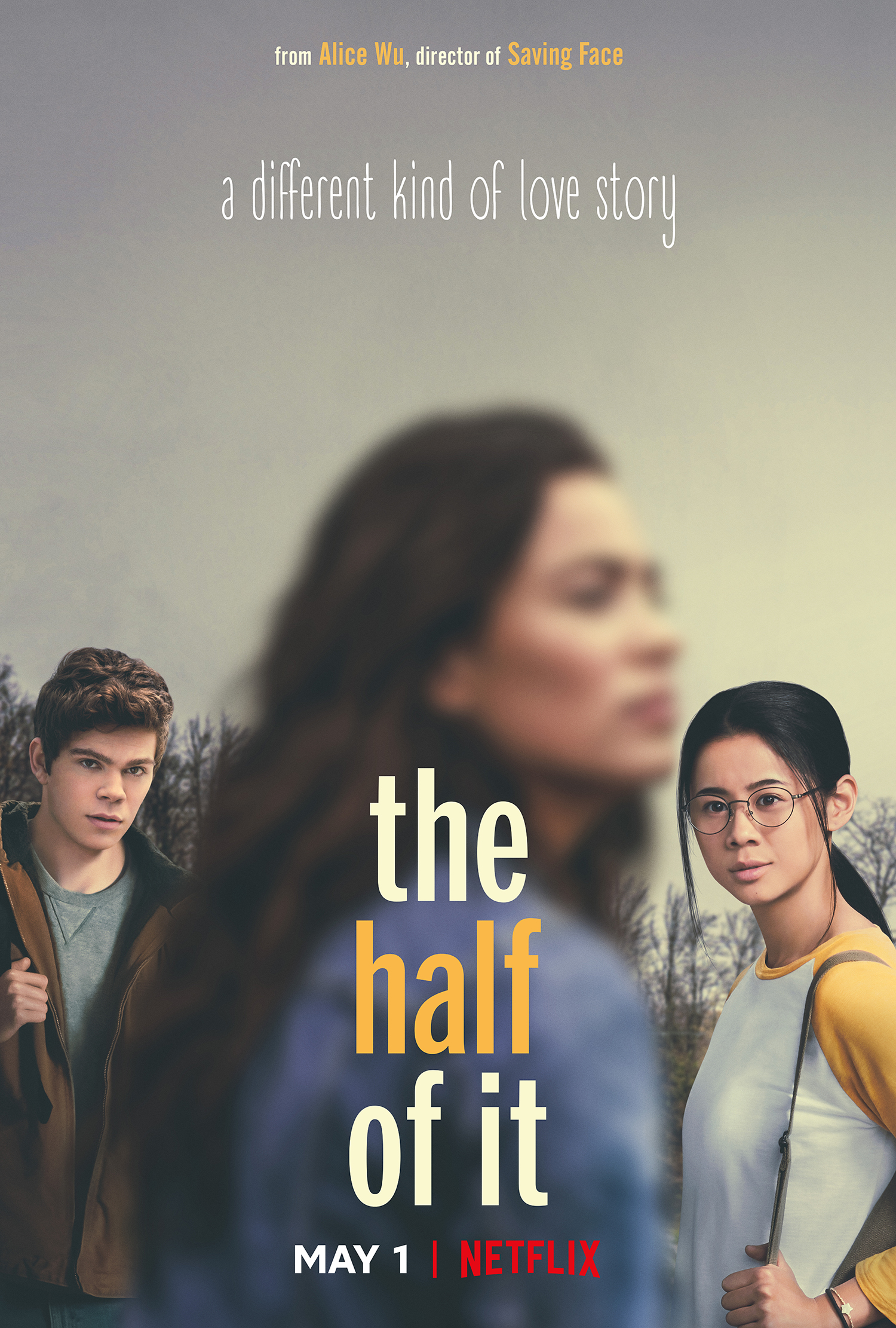

Stanford Arts has brought in a number of notable alumni to chat about their work in the arts through the “Live From Their Living Room” series. Aptly co-presented by the Asian American Activities Center this Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month, one alum stood out in particular. In mid-May, the same month that her film “The Half of It” premiered on Netflix, Stanford Arts spoke with Alice Wu (BS ‘90, MS ‘92).

Interestingly, the woman behind what many hail as the “queer Asian Lady Bird” (that is, her recent Tribeca Film Festival winner “The Half of It”) did not begin a filmmaker. In fact, she didn’t even know she wanted to work on films until she was 28, well into her software engineering career. A Bay Area native, Wu earned her bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in computer science at Stanford. Her first film, “Saving Face,” was a spontaneous product of a night class in screenwriting she took at the University of Washington while working in the area. After “Saving Face”’s notable success, however, Wu took a break from the industry to care for her ill mother, moving back to the Bay to resume her engineering career and cueing her fifteen-year industry gap between her first film and her only other — “The Half of It.” While working in tech did not lend itself to much time in the film world, she said having a career in CS before filmmaking provided her a safety net that enabled her to keep writing. She always considered herself to be a practical person, and though this set her up for a later start in the industry, she didn’t mind. Much like her queer experience when she came out at nineteen, she sought to understand herself to fully present herself.

One of Wu’s most inspiring comments in the Q&A session was how she persevered as a queer Asian woman in Hollywood: “sheer stubbornness,” she exclaimed ecstatically. Although it was hard to break into the industry, as she was limited in resources and opportunities, she never compromised her artistic integrity. This is reminiscent of the writer-director model that is growing increasingly attractive in Hollywood. Further inspired by the success of “Crazy Rich Asians” bringing a cast of Asian faces to the screen, she experienced a renewed faith in the changing scheme of Hollywood and its portrayal of the American identity.

Wu’s personal experience as a queer Asian woman has informed much of her screenwriting and directing. When asked about how her films may set the stage for media representation, especially for queer Asian women, Wu emphasized that she does not write with an agenda to rectify a societal wrong; rather, she writes about what’s personal to her: “I’m an Asian lesbian. I like to tell stories of people who don’t think of themselves typically as main characters, because usually the main character is just a straight white guy.” In many ways, this is why as a director she prefers to cast fresh, new faces, as this makes the characters feel more relatable and thus more empathetic. Perhaps this is what makes her films feel so emotional for her audience, she said, because there is an element of deep relatedness in her characters.

All of these experiences and tidbits of wisdom culminated in the production of her new movie “The Half of It.” It has been a commercial success for Netflix while also making strides in Asian and LGBTQ+ representation, with Wu’s focus on stories that reflect her personal life while being entertaining and giving a voice to different kinds of characters. The film follows Ellie, a high school student who lives with her single father in the fictional town of Squahamish. She quickly finds herself in a “Cyrano de Bergerac”-esque situation as another student at the school, Paul, asks Ellie to write letters on his behalf in order to win over a girl he’s crushing on. What Paul doesn’t know is that Ellie is slowly falling for the same girl.

The movie has such a wide appeal because it touches upon various themes like the experience of people of color in predominantly white communities. Wu draws from some of her own life experiences to portray Ellie’s life in small-town America. She has no real roots in Squahamish; she’s just trying to “make life OK,” as Wu puts it, by taking care of her father, a first-generation Chinese immigrant whose dialogue in the film is in Mandarin. As Ellie develops her sense of self, she also hopes to avoid the tragedy of just “getting by” the way her dad does.

Wu explores another important theme by focusing on the power of language and the role of words and silence. The writer-director talks about one of her favorite scenes in the film that illuminates this beautifully. Near the end of the film, Paul interacts with Ellie’s father, Edwin. Paul is notorious for his lack of skill with words, but he manages to form a substantive nonverbal bond with Edwin. While Ellie may have the most in common with Wu, she mentions seeing a bit of herself in Paul, also mentioning that Paul is “probably the most emotionally intelligent character in the movie.”

When talking about her goals as a screenwriter and as a filmmaker, Wu insists that she simply wants to shed light on the common ground shared between people that might initially seem quite different. “It’s hard to be American and not homophobic and sexist and racist, hard to be in this country and not be imbued with those attitudes,” she says, “but what is important is working on reforming those attitudes.”

This is particularly why she doesn’t tend to write specific dates into her films, as writing period pieces localizes the micro-aggressive attitudes of the story to that specific time (e.g. when she was in high school). The unfortunate reality is that these issues persist today more than ever, but that means that high school students today can relate to her experience years ago. Wu mentions drawing inspiration from movies like “Annie Hall” and “Tootsie” that portrayed characters who were “misfits.” She hopes that young filmgoers today can draw similar inspiration from stories like hers in order to — as she vocalized it so potently — become main characters in their own lives.

This article has been corrected to reflect that Alice Wu came out when she was nineteen, not in her early twenties. The Daily regrets this error.

Contact Angelina Hue at ahue ‘at’ stanford.edu and Jonathan Arnold at jarnold1 ‘at’ stanford.edu.