NOTE: This is the first in a two-part series discussing the United States’ actions toward China in the current COVID-19 pandemic. Read Part II here.

In the moments leading up to his 1960 presidential campaign, President John F. Kennedy famously remarked: “When written in Chinese, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters — one represents danger and one represents opportunity.” While this oft-quoted statement is really a misinterpretation of the Chinese word for crisis (危机 wēijī), it is nonetheless an important idea.

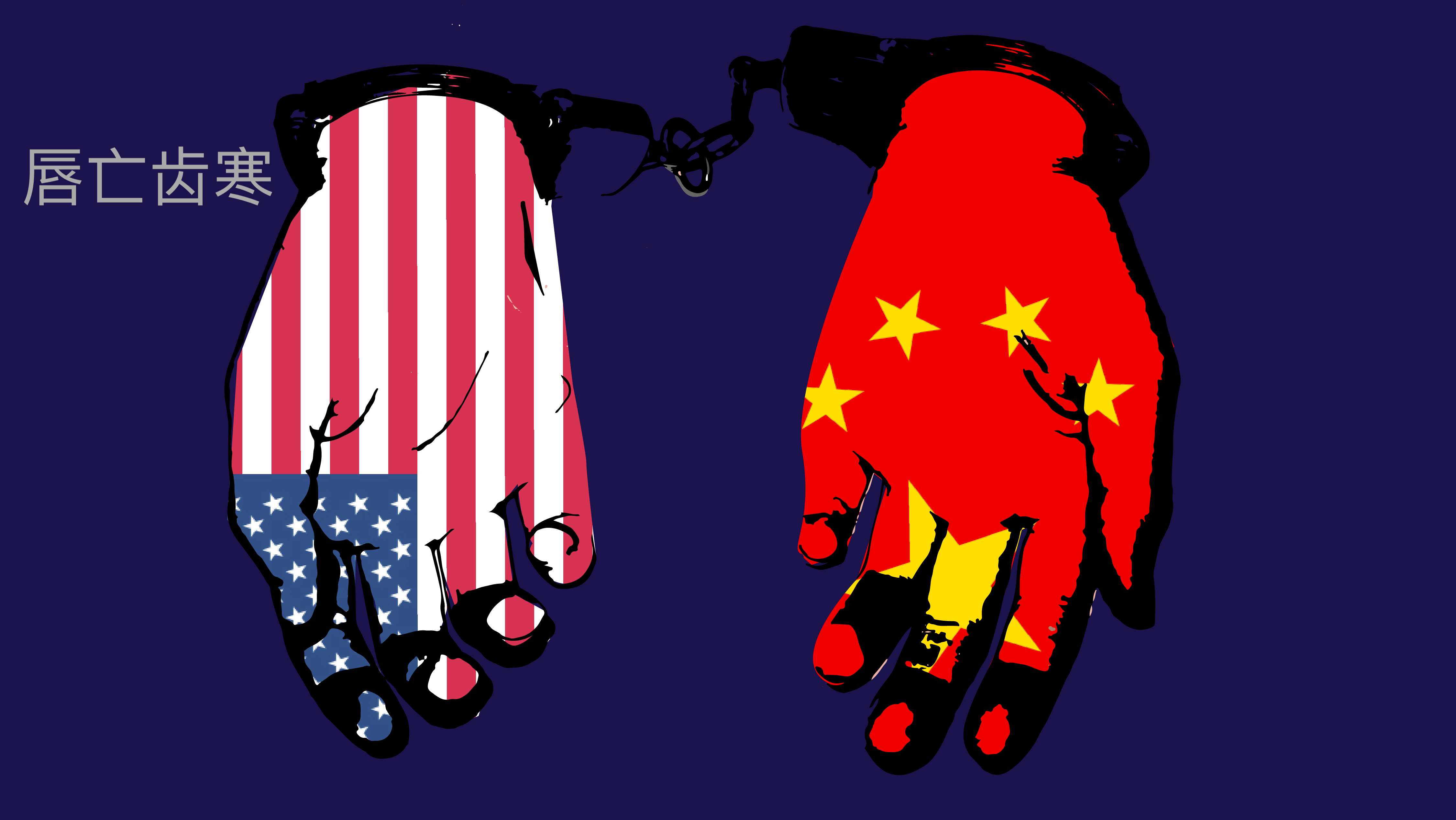

As the COVID-19 pandemic shows no immediate sign of waning, and as the global death toll has now surpassed a quarter of a million, the need for a unified, international push grows increasingly evident. The U.S. is faced with two paths: one of danger, and one of opportunity. In light of the sheer magnitude of this crisis, it is obvious what the choice must be.

Unfortunately, American leadership has instead decided to deflect blame and hurl insults, prioritizing a vague desire for hegemonic leadership over any real commitment to solidarity and cooperation. The danger is thus twofold: the virus itself, and the world’s inability to put aside its differences to optimize a response against it.

The U.S. must recognize the pernicious effects of its rhetoric. Its continued and vociferous criticisms against China create sentiments that directly endanger the lives of Asian American citizens. The incessant scapegoating plays into the hands of Xi Jinping’s government and makes the prospect of containing COVID-19 an increasingly fleeting one. This pandemic is a challenge unlike any seen before. To preserve the safety of humanity, the U.S. must start by ending its policy of antagonism toward China.

What does U.S. antagonism look like?

American leadership have espoused racist messaging, from dog-whistling to blatantly false and inflammatory statements. For instance, on April 30, President Donald Trump claimed to have seen evidence that the virus originated in a Chinese lab, but refused to provide substantiation (U.S. national intelligence have rejected this notion).

Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt recently filed a lawsuit against China for its mishandling of the virus outbreak. China is protected by sovereign immunity and cannot be sued — so the suit is frivolous. In Congress, Senator Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) introduced a bill “to hold the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) responsible for causing the COVID-19 global pandemic.” This comes on the heels of another bill introduced to the House of Representatives by Reps. Jim Banks (R-Ind.) and Seth Moulton (D-Mass.), also blaming China for the outbreak.

Following this legislation, the National Republican Senatorial Committee published a 57-page memo that characterizes COVID-19 as a “Chinese hit-and-run” and encourages candidates to simply “attack China.” It contains a detailed timeline revealing China’s supposed complicity in the outbreak and is chock full of talking points. Effectively, the administration has signaled that it intends to make xenophobia against China a central aspect of President Trump’s reelection strategy.

To be sure, the Chinese response is not without fault. The Chinese government has been criticized for its campaign of censorship toward doctors and for shutting down important laboratories. Doctors like Ai Fen, one of the earliest people to express concerns about COVID-19, have disappeared and are believed to be detained. Li Wenliang, the doctor who sounded the alarm on a potential new disease, died from COVID-19 after the government pressured him to stop “spreading rumours.” These are genuine problems that clearly demonstrate a far-from-perfect Chinese response that has cost the world greatly. We must also remember the unimaginable courage these doctors displayed in their acts of defiance.

What none of these acts of censorship suggest, however, is any intentional effort to exacerbate the pandemic. Though China may have mishandled the outbreak, a proper investigation should still only happen once the pandemic no longer constitutes a crisis.

The broad and gauche words that American leadership have employed are devoid of nuance, instead degenerating into the simple claim that China is responsible. Moreover, to a certain extent, these instances of Chinese cover-up can probably be understood as a response to American antagonism in the first place.

The social consequences of these political jabs lie in the fact that they conflate Chinese government with citizen. For instance, presumptive Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden’s recent ad claims that President Trump “rolled over for the Chinese.” In decrying “the Chinese,” Biden and other American politicians clumsily suggest that not only is the Chinese Communist Party the issue, but also the Chinese people.

Some politicians are less subtle: Sen. John Cornyn’s (R-Tex.) recent comments — that “China is to blame because the culture where people eat bats and snakes and dogs and things like that” — are especially saddening.

All these actions represent official attempts to disparage Chinese leadership. President Trump’s comments in particular ought to be viewed in a somewhat apprehensive light, given that he has previously praised China’s handling of the pandemic. Regardless, American attacks on China’s handling of the COVID-19 outbreak are increasingly ubiquitous and clearly aim to engender a sense of Chinese culpability and untrustworthiness. These efforts to scapegoat China will not save American lives.

What is the effect for Asians in America?

This finger-pointing rhetoric generates fear and anxiety which itself morphs into social stigma. As a result, more Americans now hold unfavorable views toward China than at any point in the last 15 years.

Monikers such as “China Virus,” “Wuhan Virus,” or “Kung Flu” have worsened this situation. To be sure, the first human cases of COVID-19 were reported in Wuhan, China. But these terms carry a momentous weight and a significant social stigma, far more potent than any superficial reference to the outbreak’s point of origin.

Throughout American history, Asian Americans have always been seen as an outsider, as an “other.” Coining the aforementioned terms reminds members of the Asian American community that they are seen as foreign, exotic and sometimes uncultured.

Anti-China assertions, brought up by politicians including Sen. Cornyn and reporters such as Jesse Watters (who implied that Chinese people are so desperately hungry they’d resort to eating raw bats and snakes), reveal an implicit bias against Asians as having undesirable and un-American traits, whether that be eating “exotic” types of meat or being carriers of disease.

Just like during the SARS epidemic, anti-Asian sentiments have fomented horrific violence against Asian Americans. On March 14, a young man in Midland, Texas, attacked an Asian American family, including a 2-year-old and 6-year-old, with a knife while they were shopping. The FBI has labeled this assault a hate crime.

Last week, a man tried to forcibly remove an Asian nurse from the New York subway, telling him, “Hey Chinaman, you’re infected.”

On May 8, a group of Minnesota teenagers taunted an Asian woman before kicking her in the face, posting the entire incident on social media. The rise of anti-Asian violence is not a series of independent incidents. It is a nationwide epidemic that stems from the irresponsible rhetoric of our leaders.

The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council has received thousands of reports of anti-Asian hate incidents since mid-March (future incidents can be reported here). The federal response has been deeply insufficient.

But stigma and racism do not only take the form of physical attacks. Just as Asian-owned businesses suffered in post-9/11 America, Chinese restaurants have been hit particularly hard. Public transit riders have reported hostile interactions and ignorant confrontations. Thinly-veiled microaggressions are on the rise.

Even though President Trump has stopped saying “China virus,” the damage it caused will continue to alienate the Asian American community. This rhetoric painfully reminds Asians of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, or Executive Order 9066 calling for Japanese internment, policies made in response to the same idea that Asians are a nonnative threat to America.

The fact that our leaders immediately attempt to blame the coronavirus outbreak on the Asian lifestyle is perhaps indicative of a latent danger hidden in the American psyche. When feeling threatened, we often seek comfort in alienating others, especially those of other races. We disturbingly envision racial minorities as the root cause of our troubles. In light of this pandemic, Asians eating raw bats are the reason America is under lockdown. What does this say about us? Why is it that when we hear the virus initially broke in China we instinctively avoid even sitting next to an Asian person on the subway?

By succumbing to and spreading such a simple, ignorant narrative, American politicians risk dangerously skirting past the complexities and nuances of reality. This language evokes terrible violence and only pushes our collective conscience toward alienation. Our leaders must be especially aware of the downstream effects that come from the rhetoric they employ.

In this article, we’ve discussed the damage American rhetoric against China has on the Asian community in the U.S. In the next article, we will address the political implications, arguing that antagonization dangerously impedes the global effort to stop the pandemic.

Contact Michael Alisky at malisky ‘at’ stanford.edu and Daniel Gao at dgao ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to [email protected] and op-ed submissions to [email protected].