Santa Clara County has launched a historic survey and development standards study of the San Juan Residential District — a group of neighborhoods housing Stanford faculty — after advocacy from resident faculty members and their families.

The survey will document the district in order to catalogue and protect any historically significant features. The Stanford Homeowners, a group of district residents, hope the inventory created by the survey will inform Stanford’s plans for future developments and demolitions. Group members say the survey’s results will preserve what they see as the historic character of the neighborhood, even if it is not officially designated a historic district.

But the inquiry has prompted concerns from other faculty that a historical designation would interfere with the University’s ability to build more sustainable, high-volume faculty and staff housing.

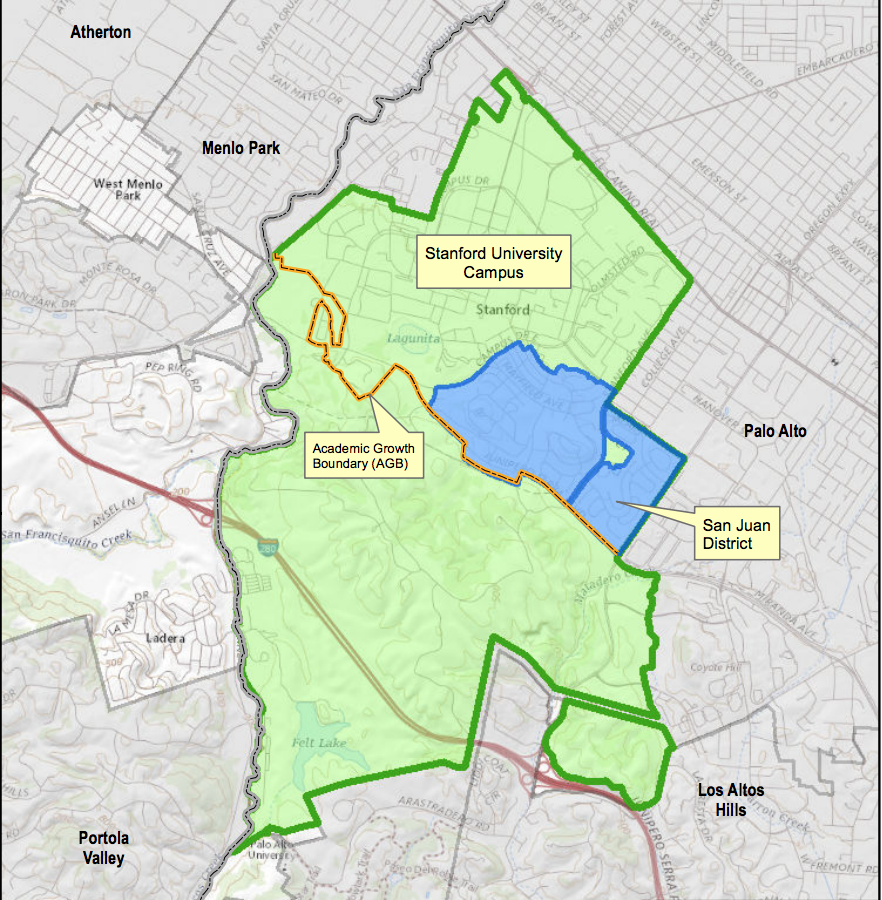

On campus, the San Juan Residential District comprises eight neighborhoods and houses 860 faculty and their families. At least nine of those residents have identified themselves as members of the Stanford Homeowners; Sandra Pearson and Sunny Scott, who are spearheading the historic survey initiative as spokespeople for the group, say there are more than 200 other members who wish to remain anonymous due to fears of backlash from the University.

Both women have lived on campus for more than 30 years. Sandra’s husband, Scott Pearson, is a former agricultural economics professor; and Sunny’s husband, Kenneth Scott J.D. ’56, was a professor at Stanford Law School before passing away in 2006.

Sunny and Sandra oppose Stanford’s housing plans for their neighborhood, which include tearing down two existing houses and building seven new houses in their place.

Though Sunny and Sandra say they recognize the pressures of the housing crisis and have nothing against high-density housing, they want to preserve the district’s architectural style, which Sandra said attracts new faculty and “adds intrinsic value to its occupants.”

The new buildings, Sunny and Sandra say, are architecturally inconsistent with their surroundings and will degrade the character of their district.

“We see our residential areas evolving to meet future housing needs,” Sunny said. “Our goal is to define development standards and zoning to preserve our neighborhoods as they evolve.”

Ultimately, the two women want preservation of the neighborhood’s character, consistent enforcement of regulations, clear building codes and transparency regarding Stanford’s plans for residential development.

Many of their neighbors, however, think the survey is the wrong way to achieve that goal.

County meeting draws opposition

The county held its first public meeting about the survey on Feb. 27, drawing dozens of district residents in vocal opposition to the initiative.

During the meeting, Santa Clara County Principal Planner Bharat Singh outlined the project timeline, including a survey of the Residential District from April to August, two more public meetings and a final Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors’ hearing in spring 2021. The county has allocated $50,000 for the survey, according to Singh.

But some meeting attendees called for denser housing to solve the housing crisis in the area, telling The Daily that the supporters of the survey are a small, unrepresentative group within the community. When they asked Singh whether the purpose of the survey was to stop Stanford from turning existing housing units into denser and more affordable ones, he said the answer depended on the results of the survey.

“For junior faculty who are trying to teach at Stanford, the question of whether or not we can come take this amazing job and stay to have a career depends, more than anything else, on whether we can get housing,” geophysics assistant professor Dustin Schroeder told The Daily.

But Schroeder also said the situation is difficult, noting that many senior faculty members have strong emotional and financial ties to their homes and the neighborhood.

Residents also expressed concerns that they would lose some control over their homes if the neighborhood were to be designated as historic. Some questioned the need to bring the county into Stanford’s housing decisions, wishing instead to work internally with Stanford Campus Residential Leaseholders (SCRL).

“We need to be as flexible and thoughtful as we can, and adding an external body and additional bureaucratic restraints limits our ability to do that,” Schroeder said. “I’m more hopeful that we can come up with creative and thoughtful solutions within the Stanford community.”

Stanford Community Relations & Land Use Communications Officer Joel Berman wrote in a statement to The Daily that “Stanford will continue to work collaboratively with homeowners and Santa Clara County to identify strategies for on-campus development that allow the building of much-needed additional housing while maintaining the character of the neighborhoods.”

“We feel this constructive approach is the best avenue for addressing the interests of residents and the university,” he added.

Contact Marianne Lu at mlu23 ‘at’ stanford.edu.