Though artificial intelligence (AI) will undoubtedly impact the economy, it will improve jobs, not replace them, said former provost and current co-director of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) John Etchemendy.

“We as an institute focus on ways in which the current technology, and hopefully future technology as well, can be used not to replace humans but rather to enhance humans, to extend what humans can do, to enrich human lives,” said Etchemendy, who is also a professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

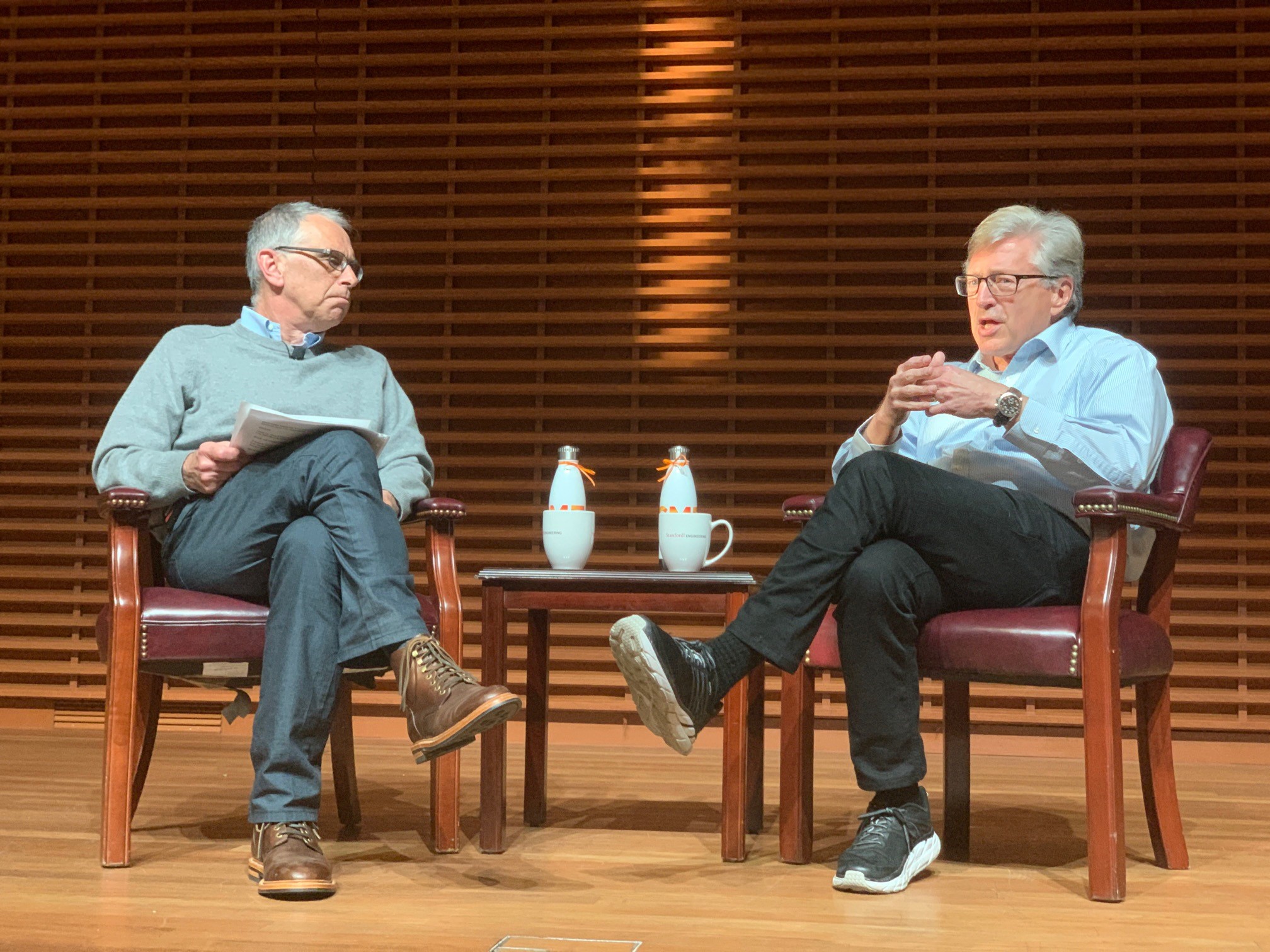

Etchemendy spoke Thursday at a live taping of the radio show “The Future of Everything.” The show, hosted on SiriusXM by bioengineering professor Russ Altman, explores how technology, medicine and science shape the world.

Etchemendy told Altman that contemporary AI is limited.

“It is simply a way of programming computers to get them to perform functions that were infeasible using traditional programming techniques,” he said. “But it’s nothing more than that currently.”

Even in its current form, however, Etchemendy said AI is going to affect everything that people do.

“It’s going to have impacts on every piece of our lives,” he said. “It already has, whether you know it or not. … We need to understand what the impact is going to be. We need to look at its impact on humans, on society, on cities, on the workforce, the economy, international security.”

In response to fears that AI will lead to a loss of jobs, Etchemendy told Altman that “it will be slower than people are currently anticipating.” While he said “there will be disruptions” in the workforce, he pointed out that in every technological revolution, the number of jobs has increased.

“I do not for a minute believe that we will end up with no jobs and lots of robots,” he said.

Instead, he believes AI will improve jobs, removing the tedium. Utilizing the example of the long-haul truck driver, Etchemendy suspects there will no longer be cross-country driving in five to 10 years, though he predicts drivers will still be needed for carrying products shorter distances.

“That actually makes the truck driver’s job better,” he said. “You won’t have to leave home for five days at a time; you can sleep in your own bed at night.”

When asked about careers that require a human element, such as elder care, Etchemendy told Altman that they present a “difficult problem.”

He said, though, that AI can enhance what human caregivers do without replacing them, such as “providing devices that can observe when the elder has fallen out of bed, or fallen and hurt him or herself.” He added that AI might allow fewer caregivers to provide care to larger numbers of people.

“There are ways to use this technology that are going to allow us to provide things like elder care much more broadly,” he said.

Both Etchemendy and Altman emphasized the broad scope of AI technologies.

“Everybody who has a smartphone has access to certain AI tools,” Etchemendy said.

Altman said that “every Google search that you ever do is assisted by AI, and every purchase decision, whether you like it or not, is nudged by AI.”

As for the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI), AI that would be capable of doing most of what a human can do, Etchemendy is skeptical.

“There are companies that are currently working on AGI,” he said. “You heard it first here: They’re going to fail. We do not yet understand human intelligence well enough to make that a feasible goal.”

Contact Emma Talley at emmat332 ‘at’ stanford.edu.