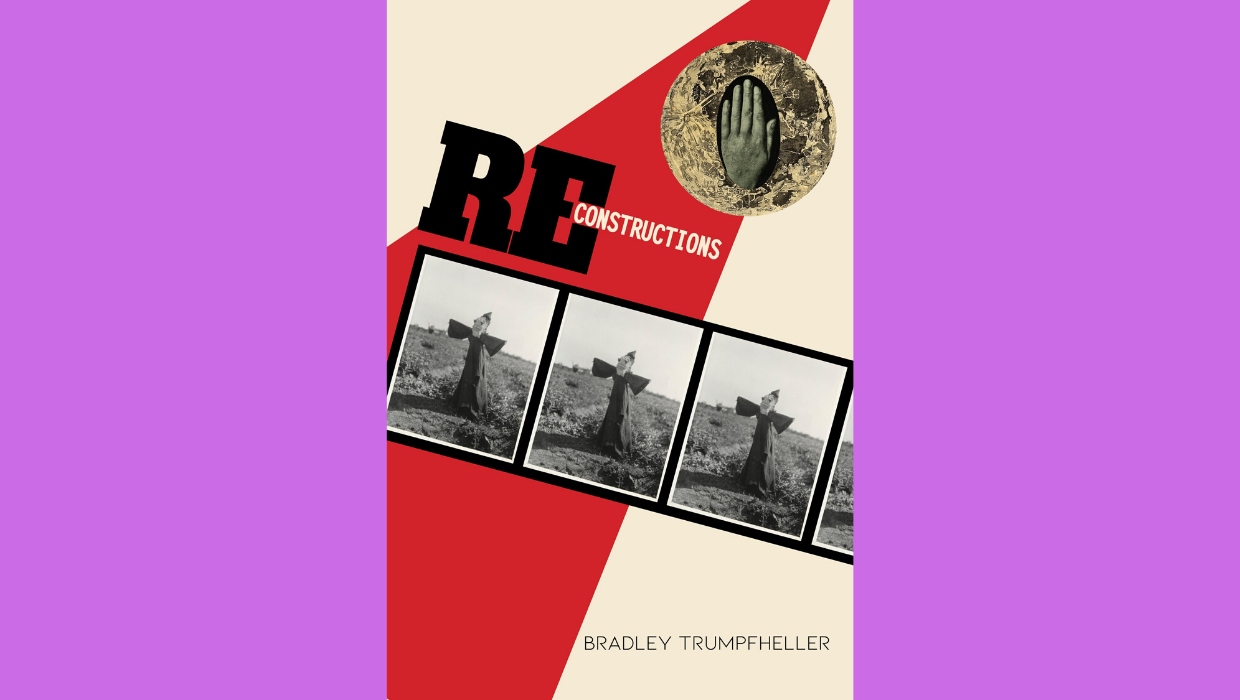

Bradley Trumpfheller’s poetry chapbook “Reconstructions” explores beauty, grief, disorder and more, redefining these concepts through fresh feats of language.

Released in late January, Bradley Trumpfheller’s poetry chapbook “Reconstructions” from Sibling Rivalry Press is, among other things, completely and utterly glamorous. With poetry, I’m the type of person susceptible to falling into the habit of considering only what seems beautiful, and what isn’t. Maybe it’s not enough for a poem to simply be beautiful, or at least beautiful in a way that remains unaware of the language that it is built upon. Trumpfheller’s chapbook is certainly beautiful — there are nightclubs in this collection, as well as birds, lip gloss, vanity mirrors, the moon — but Trumpfheller’s poetic beauty is constantly reinvented, re-examined. And, of course, reconstructed. If everything touched by Trumpfheller’s poetry is a thing of beauty, it is beautiful only in the briefest of moments: In their poem “Hearing Loss,” a cardinal is seen as only “its red instant of form.” Here, then gone.

They begin the collection with the poem “Do You Kiss Your Boyfriend With Those Verbs,” which elicits a series of redefinitions. Trumpfheller writes:

“instead of loss, say every day we are moving / closer to when getting out of bed seems possible.”

And:

“never say heaven unless you mean the past / tense of to heave. as in I am heaven towards what… / we might have called / each other.”

Maybe this is true too: Maybe every loss is meant to be resurrected, and every heaven a way for us to reach our past and future names. Trumpfheller writes with a deft control of language, but with an awareness of its limits: Maybe the best way we can talk about the sky is to say simply that “moons moon” and “stars starry that way.”

Interspersed throughout the collection is a series of poems denoted only as“from Reconstructions.” True to their titles, these poems cycle through previously touched upon images. For instance, in “Asphyxia,” the speaker is cynical:

“show me / the place no one wants me dead & I’ll show you a girl dragging / a door from the water.”

In the “Reconstructions” poem immediately following, Trumpfheller reinvents this possibility:

“But say we’re not being hunted. Say instead / of shotguns, the men / hide rhinestones under their pillows.”

In this way, Trumpfheller pushes images that sing with wonder and awe without releasing the tension — the violence — inherent throughout their poems. It is still possible, without any contradiction at all, for “rhinestones” and “shotguns” to exist in the same train of thought. If everything touched by Trumpfheller’s poetry is beautiful, it’s a type of beauty that doesn’t obscure anti-trans violence, but rather lives with it.

In one of the final lines of the poem, they write:

“Pistons Lipstick (my god) Little dimples of wind.”

Even after finishing the collection, I always find myself drawn back to this poem and, specifically, this line, which continues to devastate me every time I arrive at it. The speaker’s awe — “(my god)” — if it could be called that, lives in brief snapshots of the spectacular and horrific. The beauty in this image is a beauty that stands in awe of itself, but also a beauty that refuses to be deluded by its own brilliance. In a later “Reconstructions” piece, Trumpfheller crafts the image of “the country / …stitched w/ a parataxis gold.” They then write:

“Do not mistake me – / There are worlds where all of this is true / & we still do not survive.”

Even in their most picturesque images, Trumpfheller never lets the reader get too caught up in the fantasy of a world where men hide “rhinestones” instead of “shotguns … under their pillows”; there is almost always a point at which Trumpfheller consciously pulls the reader out of these beautiful, but unsustainable, images.

Trumpfheller’s collection is enraptured with godliness: in the poem “Catalog of Divine Encounters in Mobile County, AL,” Trumpfheller begins with a list of divine anecdotes: a photograph of a “cross-shaped water stain” or a sighting of “a girl / …who claimed she could heal the sick.” Although these encounters are presented mostly as anecdotes from third-person accounts, there’s something wondrous about these brief, miraculous moments. It’s another way of being awestruck.

Godliness, in Trumpfheller’s mythology of disco and desire, is a kind of rapture, wonderment and, inevitably, loss. In “Tomorrow, No, Tomorrower,” Trumpfheller writes:

“I said my lord. I thought / My god. O moonstruck. O gladracket.”

As “Catalog of Divine Encounters in Mobile County, AL,” moves toward its final lines, the poem collapses into itself. As the list of divine encounters ebbs off, Trumpfheller writes:

“Nobody heard my uncle / cadaver himself. Even the birds no longer sound / useful. When I pray for rain I pray / the trees die before it comes.”

I don’t know what to make of a poem that begins with a divine sighting and ends with a prayer for death; Trumpfheller creates a beautiful mess, and such a controlled one at that. Nothing godly in Trumpfheller’s poetic landscape is wholly wondrous or permanent, and violence lurks at the edges of what we know as miracles.

Trumpfheller’s “Reconstructions” reinvents awe and beauty, violence and grief. Trumpfheller’s collection is not a collection about desire, but it is a book so full of it: for a world where “none of us began with names,” for tenderness, for vanity mirrors and good lipstick, for “glitter on [the] skyline.” “Reconstructions” is not a book about fantastical reimaginings, but I am in love with the worlds within Trumpfheller’s reconstructions: the worlds without pronouns, as well as the worlds in which we are still astonished by simple but beautiful things — the moon and her stars, the mountains that “[flinch] apart like doors.” In “Reconstructions,” beauty —trans beauty, the beauty of the body and of the natural world — is haunting, devastating, glorious — yes, always, always glorious.

“South star and the ocean at our backs,” Trumpfheller writes in their penultimate poem of the chapbook.

“South star and the ocean at our backs. / At our backs. / Makes us a paradise. / Paradise at our backs makes us a paradise. / And the branches of the linden rosing to touch the branches. / Yes. / It’s supposed to be this bright.”

Contact Lily Zhou at lilyzhou ‘at’ stanford.edu.