Recently I’ve found myself in settings where earnest, serious-minded people discussed topics that I had difficulty not finding pointless, and the story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes” returned to my mind rather suddenly.

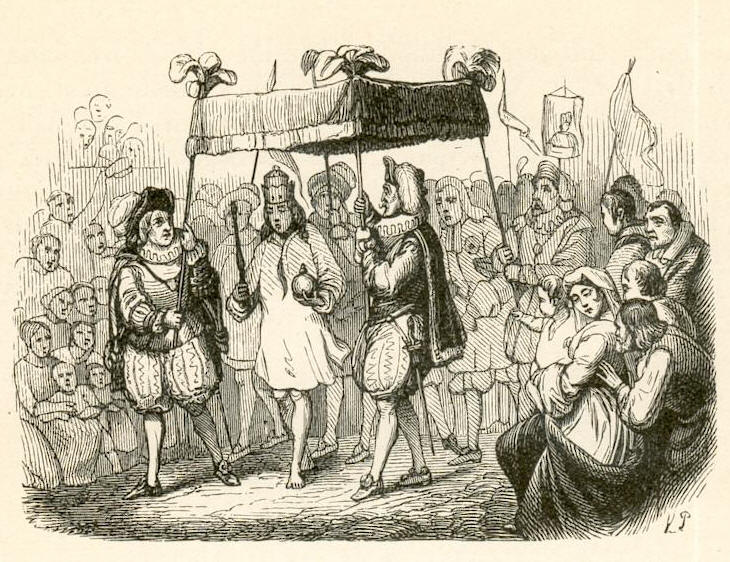

The clothes, the weavers tell the Emperor, are invisible to any who are unfit for their positions or incompetent. This powerful lie sets in motion the ridiculous conclusion of Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes” (1837): the Emperor parades through the town in his undergarments after the weavers dress him in the “invisible” clothes, which in fact do not exist. The courtiers, the townspeople and the Emperor himself all keep up the pretense that the magnificent clothing exists, out of fear, Anderson writes, of appearing unfit for their positions or incompetent. Only when a child blurts out the truth — “he isn’t wearing anything at all!”— is the spell of collective pretense broken.

This tale appears to have a number of rather trite morals: the dangerous vanity of not wanting to appear incompetent, the perils of going along with the majority opinion, the power of the childlike mind to pierce through lies. But we also leave the story, I suspect, both laughing at the Emperor and the courtiers and the townspeople and thinking that we would not be so stupid as to fall for the trick. The second thought is what I want to challenge in this article. It’s not obvious to me that we serious, reflective people would see through the charade. And it’s not obvious to me that we should.

We the readers know that the Emperor wears no clothes, but we know this not because we observe it. Rather, our omniscient narrator kindly informs us of this point. In a dramatic irony, we know from the start that the weavers are con men, while nobody in the story does — besides, of course, the con men.

Suppose we engage in a thought experiment and pretend that we are townspeople. A horn is sounded, and the announcement made that the Emperor will be passing through, wearing clothes of such great splendor that only the worthy can see them. In due time, the Emperor arrives, flanked by his courtiers, and you hear the murmur of amazement and whispers of the clothes’ beauty. When he passes into view, however, you see nothing but the Emperor in his undergarments.

What should you think? All around you people are apparently admiring the garment, and the Emperor seems immensely pleased. Is it more likely that everyone is playing a big trick on you, or that indeed the clothes are visible to almost everyone, but not to you?

If invisible clothing is too much a stretch, imagine instead that you see the Emperor wearing clothes that appear incredibly gaudy, but that everyone else seems to think are the picture of refinement. Is it more likely that everyone else is wrong, or that you are somehow missing something?

Or imagine you are attending an academic workshop where a scholar presents their work, and it is received earnestly. The participants are engaged and ask considered questions, but you cannot figure out why the topic being discussed should matter at all. Should you think that everyone else is talking about nothing of importance, or that they understand the stakes and you don’t?

In this last example, it’s far from clear that we should be confident that the discussion has no clothing, so to speak. And this suggests that the condition of the townsperson is more difficult than we at first thought. Just as I might reasonably think the scholars are respected figures in their field, and so are unlikely to be talking about nothing, the townsperson has at least some reason to trust their fellow townspeople, if not the Emperor and courtiers.

The story of the Emperor’s new clothes returned to my mind because the example of the academic workshop was becoming an increasingly real conundrum for me. I found myself in settings where earnest people discussed topics that I had suspected were pointless. At the same time, the fact that such topics seemed to me pointless did not seem sufficient evidence to suggest they were actually pointless. When in a room of earnest, serious-minded people at Stanford, I thought, one should assume that what’s going will make some measure of sense and not be pointless. Yes, it was possible that some conversations were pointless, but it was also possible, and perhaps more likely, that I was simply missing the point.

It looks the same to you, the villager, whether the Emperor is wearing no clothes or whether he is wearing clothes you cannot see because you are incompetent. How are you to know? And in the same way, in the room of earnest, serious-minded Stanford people, I am not sure I can think my way out of the quandary and figure out whether there is some point or whether there is no point.

If a person thinks he is just, the philosopher Bernard Williams observed, but everyone else treats him like he is unjust, “there is nothing to show whether he is a solitary bearer of true justice or a deluded crank.” I see myself in a similar situation when I can’t find the point. Is there anything to show whether I am a solitary bearer of points or simply deluded and incompetent?

In the story of the Emperor’s new clothes, there is an empirical test. The weavers know the truth. Should they choose to divulge it, everyone would be informed of their true position — they were correct to see no clothes, as there were no clothes to see. But as a final twist, consider: what if the weavers themselves thought they were weaving real clothing, albeit clothing that they couldn’t see because they were not worthy enough either? In such a story, we the readers and the omniscient narrator would still know the truth — that there is no clothing — but nobody in the story would know. And this version of the story seems closer to the real-life condition I find myself in, sitting in the room with earnest, serious-minded people and failing to find the point.

Contact Adrian Liu at adliu ‘at’ stanford.edu