Last week, the top 12 candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination went head-to-head on live television, vying to capture the nation’s attention in 60-second sound bites. In each debate, the Democrats have grappled endlessly with one big question: whether or not the party should shift leftward. That intra-party tension certainly won’t disappear anytime soon, but if a Democrat wins back the White House, another big question might take priority: whether or not Democrats should alter the rules of the game so they can get things done.

If the Senate stays in Republican hands, a Democrat in the White House will turn to executive actions and rule-making through agencies to enact his or her agenda, circumventing a gridlocked legislative branch to push through important policies. Both Democrats and Republicans alike have attacked the so-called “imperial presidency” when a member of the other party sits in the Oval Office, but unilateral executive decision-making is now standard presidential practice.

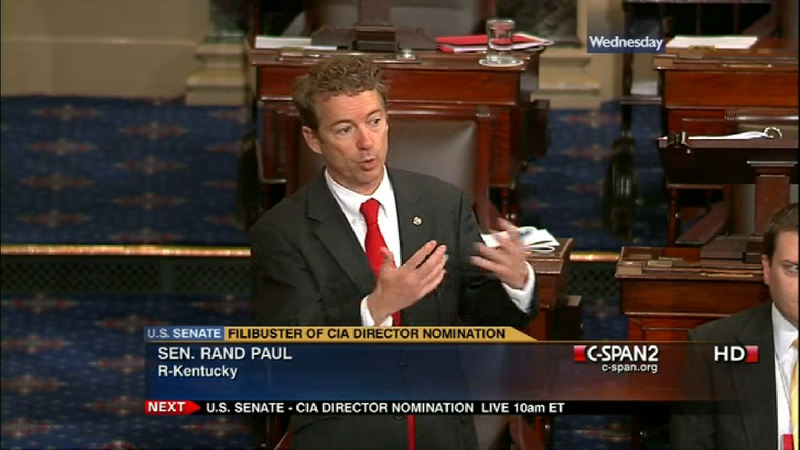

If the Senate turns blue, the Democrats will confront a more controversial procedural dilemma: whether or not to eliminate the filibuster, which effectively creates a 60-vote threshold to pass most legislation. Doing away with the filibuster only takes a simple majority vote. Although the decision to keep or eliminate the filibuster ultimately rests with the Senate itself, this question has become somewhat of a progressive litmus test, with groups like Indivisible calling on Democratic presidential candidates to come out against the filibuster. Declaring opposition to the filibuster signals a willingness to govern aggressively, put the popular will above procedural roadblocks and move from high-minded rhetoric to tangible change. A few candidates, including Senator Warren, are wholeheartedly in favor of eliminating the filibuster, a few are strongly against it and the vast majority are open to it, but not committed either way.

At first, I found “eliminate the filibuster” to be a frustrating progressive rallying cry—perhaps even a dangerous one. I preferred the ethos that Michelle Obama set out in her 2016 Democratic National Convention speech: “When they go low, we go high.” When Senator Mitch McConnell eliminated the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees, enabling Trump to name two Supreme Court justices despite lack of bipartisan support, Democrats decried the degradation of norms and McConnell’s unabashed partisan aggressiveness. Wouldn’t it be hypocritical for Democrats to follow in his footsteps and pollute our politics even further? And, if the Democrats eventually ended up in the minority again, wouldn’t they regret their predecessors’ rash decision to vest more power in the majority party?

On the other hand, I could see how scrapping the filibuster could be a no-brainer for a committed progressive. In the case of unified Democratic control, maintaining the filibuster would be the death knell for implementing progressive policy. Imagine if the Democrats controlled both branches of Congress and the White House, but fell short of 60 seats in the Senate. By stubbornly adhering to a rule that is completely within their capacity to eliminate, the Democrats would strip themselves of the ability to pass any meaningful legislation. They would be criticized for dysfunction and cowardice, for unilaterally disarming against a party that is willing to play dirty, for abandoning the bold ideas that they put forth on the campaign trail. By exercising restraint, Democratic senators would leave the legislature powerless to address gun violence, climate change, human rights abuses at our border and rampant inequality—abandoning the voters who elected them not to wring their hands, but to tackle these crises.

While this scenario is frustrating, the filibuster does appeal to an important philosophical principle: protection of minority rights. An unchecked majority, as James Madison wrote in Federalist #10, can “sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest both the public good and the rights of other citizens.” Counter-majoritarian mechanisms, like the filibuster, put some power in the minority’s hands, mandate greater consideration of opposing perspectives and force us to evaluate the harm that popular decisions could impose on underrepresented groups. Democrats should defend these liberal principles, not contribute to their death. Plus, if we ever hope to temper our dangerously polarized politics and make bipartisanship possible again, we ought to advocate forbearance and cooperation—not wield procedure as a weapon and make a party line out of hypocrisy.

I started to rethink this high-minded philosophical defense of the filibuster when I picked up some not-so-light summer reading: “Master of the Senate”, the third 1,000-page book in Robert Caro’s four-volume biography on the life and career of Lyndon Johnson. (As dry as that may sound, it’s an absolute page-turner.) The book—which is as much a detailed portrait of the United States Senate as it is a biography of Lyndon Johnson himself—culminates in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, a bill that, albeit being relatively weak, enacted the first federal civil rights protections since the end of Reconstruction. The book’s political drama rarely unfolds as a straightforward up-down vote on a bill, but rather, through fights over the intricacies of parliamentary procedure. The segregationist Southern Democrats—who first taught Johnson that the Senate rulebook was the key to dominating that institution—spent decades using the filibuster to prevent the Senate from even taking up the question of civil rights. They didn’t just threaten to filibuster legislation itself—they filibuster any motion to put a civil rights bill on the Senate calendar.

Although the filibuster is often described as an important bulwark of minority rights, “Master of the Senate” portrays the filibuster as a bulwark of state-sponsored racism. As segregationist senators filibustered to defend their so-called “way of life,” Black southerners, already barred from the ballot, were left defenseless. Yes, the filibuster has historically protected minority voices—but not minorities that are at the greatest risk of oppression.

Today, if Democrats were to win the majority in the Senate, the filibuster would empower a minority that already enjoys a massive structural advantage in the upper chamber: the people of less populated states. The Senate is a textbook example of malapportionment, meaning that every legislator represents a different number of people. California’s 40 million people and Wyoming’s half a million each have two senators, which effectively dilutes the voices of people from more populous states. Since smaller, more rural states also tend to be more conservative, Republicans are overrepresented compared to their numbers in the American population overall. In this case, to defend the filibuster on principled grounds would require an explanation of why small-state voters are such a morally salient minority that they deserve both overrepresentation and disproportionate veto power.

Teddy Roosevelt once proclaimed: “A great democracy has got to be progressive, or else it will soon cease to be either great or a democracy.” With the filibuster in place, Roosevelt’s grim prophecy for our democracy might likely come true. In an ideal world, three-fifths of the Senate would easily agree that we need aggressive climate action, humane immigration policy, common-sense gun laws, living wages, civil rights protections for LGBTQ+ people and universal healthcare. However, in the absence of such consensus, the filibuster will impede a Democratic Senate from keeping up with these challenges, compounding the body’s built-in bias against progressivism and calling into question the efficacy of our institutions. Although the filibuster might seem like a necessary guard against majority tyranny, it has historically been weaponized to protect a privileged minority at the expense of an oppressed one. As much as I wish to cling to Michelle Obama’s principled mantra, I believe our legislative branch ought to meaningfully respond to our country’s greatest crises. If filibuster abolition is the only way to make that possible, I believe it is a pathway worth pursuing.

Contact Courtney Cooperman at ccoop20 ‘at’ stanford.edu.