This article is published as part of the Music + X series, designed to introduce you to classical music that applies to aspects of everyday life. This week’s playlist, featuring all of the music discussed below and more, can be found here.

On September 11, 1973, following years of political conflict within Chile as well as economic warfare on the country from the Nixon administration, the democratically elected president of Chile was overthrown in a military coup.

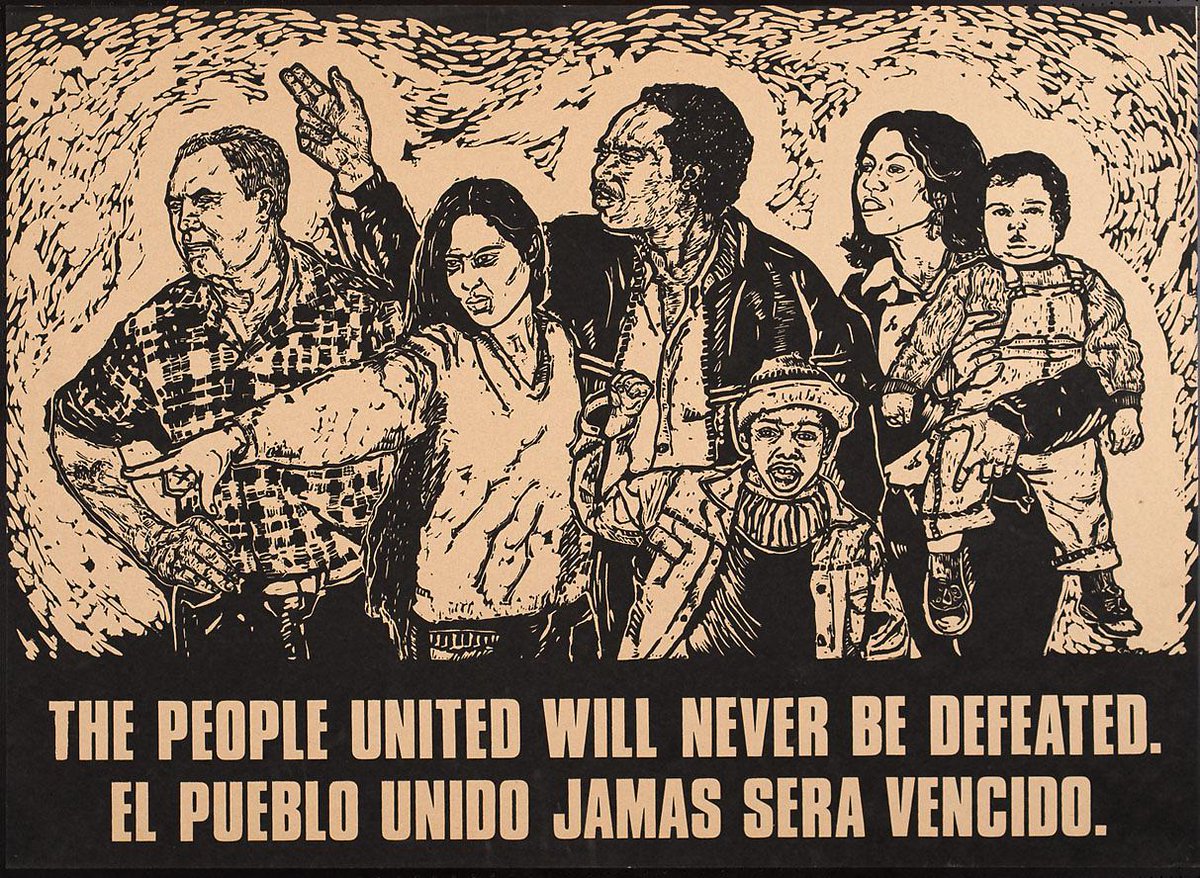

In the military regime that ensued, composer Sergio Ortega’s protest song “¡El Pueblo Unido, Jamás Será Vencido!” (“The people united will never be defeated!”) became an anthem of the resistance to dictator Augusto Pinochet’s rule. The song begins with the above chanted words over a powerful chord progression, before flowing into a more reflective, sombre tenor that nonetheless maintains the determined defiance of the opening.

That music and revolution go hand in hand shouldn’t surprise us. The rousing spirit of protest songs like “¡El Pueblo Unido” in Chile, or “Go down Moses” of the American Underground Railroad can be among the most powerful vehicles for expressing the pathos and impetus behind an uprising of the people. In today’s installment of Music + X: classical music’s perspectives on revolution.

Rzewski: The People United Will Never Be Defeated

Three months before the coup, in June of 1973, Sergio Ortega was walking through the plaza in front of the Palace of Finance in Santiago. He recounts:

“[I] saw a street singer shouting, ‘The people united will never be defeated’ – a well known Chilean chant for social change. I couldn’t stop, and continued across the square, but his incessant chanting followed me and stuck in my mind … When I reproduced the chant of the people in my head, the chant that could not be restrained, the entire melody exploded from me: I saw it complete and played it in its entirety at once. The text unfurled itself quickly and fell, like falling rocks, upon the melody.”

Where the text of the chant served as Ortega’s inspiration, American composer Frederic Rzewski takes Ortega’s song as the starting point of his composition “The People United Will Never Be Defeated,” a set of 36 variations for piano on Ortega’s theme. The choice of the theme-and-variations format is a clever metaphor — variations on a theme will differ from one another in some respect, but they are united in the fact that they arise out of the theme.

An ingenious structure within the variations extends this metaphor of unity in diversity. The 36 variations are split into six cycles of six variations each. In each cycle, the six variations introduce different musical relationships, the sixth of each cycle bringing the different relationships together in a whole. Similarly, each of the six cycles develops a different character. As Rzewski explains: “the third cycle is lyrical, the fourth tends toward conflict, the fifth toward simultaneity (the fifth is also the freest), and the sixth recapitulates.”

The point about unity is subtle: what unites these variations is not only that they arise from a common theme, but that they combine and integrate into a greater whole. A platitude, perhaps, but we often forget the truth in platitudes, and sometimes it takes a complex, extended work like the hour-long “People United” to remind us of the power and necessity of ideas like “unity.”

To muzzle a free press is to stifle the voice of the people and sever the tenuous tie between the common many and the ruling few. So when this particular freedom is compromised, political unrest is almost inevitable — such was the case in early 1900s Finland. At the turn of the century, the country struggled under harsh press restrictions imposed by the Russian government. Russia had gained rulership over Finland after a successful conquest against Sweden; subsequent press restrictions reflected Russia’s desires to forcefully integrate Finland into Russian customs and governance.

Like many other proud Finnish people, well-established composer Jean Sibelius strongly protested this press censorship. Sibelius’s musical talent and popularity gave his works a large audience, and his tone poem “Finlandia” went on to become one of his most regarded and consequential compositions, especially at the time of its release. Composed as one of a series of nationalistic works, Finlandia was the magnum opus of the composer’s revolutionary works.

The tone poem opens with an ominous horn choir, harkening to the looming threat of Russian suppression. But soon the piece blossoms from a sparse, minor melody into a rich orchestration, transforming the threatening horn theme into a triumphant melody dripping with Finnish patriotism.

The nationalistic jubilance of “Finlandia”’s opening eventually dissolves into the most famous section of the tone poem: a hymn-like woodwind chorus, reminiscent of common Finnish folk songs. Sibelius seems to pause here, reflecting on his love for Finland and, in turn, the beautiful freedom Finland was once able to provide for its people. Many today assume that the hymn was derived from traditional folk tunes, but Sibelius actually composed the melody. It became one of Finland’s most important national songs well after “Finlandia” first premiered.

From the lilting sensitivity of the central hymn arises an exalted “Finlandia” once more. The piece ends as it began, with a boisterous horn line howling musical cries for Finnish freedom. Sibelius himself never participated in any politics or protests, but “Finlandia” is the closest he came to outright revolution. Indeed, his work almost explicitly stated the desires of Finnish liberation and sparked a nationalistic fervor in many of his audience. So obvious were its intentions that orchestras were often forced to perform the piece in secret, writing alternative titles to hide from Russian censorship.

Rzewski’s “People United” depicts and comments upon the act of protest that was the revolutionaries’ singing of Ortega’s song. But “Finlandia” is itself an act of protest. The two very different contexts in which Rzewski and Sibelius wrote are displayed in their different perspectives on revolution. Rzewski analyzes from a distance, and reflects on the components that make up a work of protest. Sibelius, on the other hand, has a motive closer to Ortega than Rzewski: Living in the midst of political turmoil, he is not in the business of showing, but in the business of rousing the people.

Recommended Listening:

- Frederic Chopin, Etude Op. 10 No. 12 “Étude on the Bombardment of Warsaw”

- Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle: La Marseillaise

- Dimitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 11, “The Year 1905”

Contact Elizabeth Lindqwister at liz ‘at’ stanforddaily.com and Adrian Liu at adliu ‘at’ stanford.edu.