“They’re not here for a lesson in gender and sexuality. They’re here to mark my throw.”

After acknowledging this, track and field thrower Jaimi Salone ’20 said it was no less painful to be reminded of it on April 6, at Stanford’s annual Big Meet against Berkeley.

The student-athlete’s pain wasn’t physical, nor was it the sting of defeat. In fact, Jaimi seized victory in the shot put that day, launching the four-kilogram weight a personal-best 14.42 meters in front of the home crowd — a crowd to which Jaimi’s gender was incorrectly represented.

“I got misgendered, like, four times in a minute by the announcer,” said Jaimi, who was in the ring and preparing to throw as the misgendering occurred. “It was over the loudspeaker … it hurt.”

Though Jaimi competes for the women’s track and field team, the thrower identifies not as she, but as they. Jaimi is genderqueer, or nonbinary, meaning they do not identify exclusively as male or female.

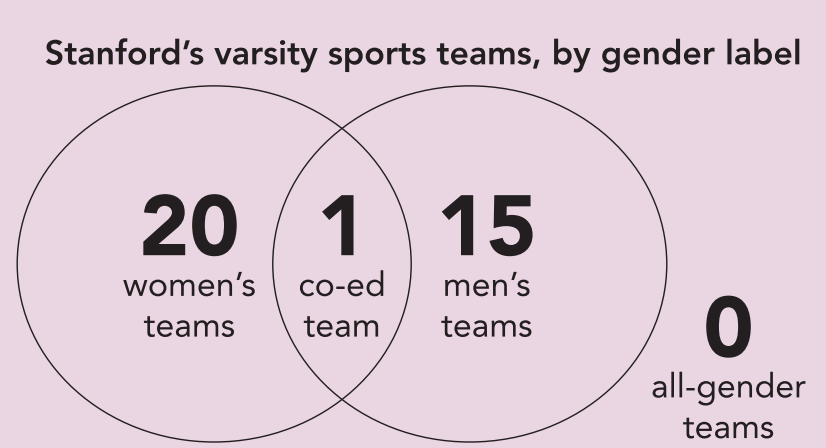

The world of sports, meanwhile, is largely built upon a gender binary, with the vast majority of collegiate and professional teams competing in divisions labeled “men’s” or “women’s.”

“Me being genderqueer, I’m just doing the best approximation given the options I have,” Jaimi said.

Following the incident at Big Meet, a teammate told Jaimi to channel their frustration into the next throw — the one in which Jaimi set a new personal best and sealed their victory — but that didn’t change the fact that they felt “let down” by the misgendering.

Jaimi has decided against bringing such concerns up directly, citing the officials’ ages and apparently good intentions as evidence that their microaggressions are unintentional. There’s no need to risk further misunderstanding.

Instead, Jaimi focuses on throwing. But the microaggression of misgendering doesn’t go away.

Earlier this year, Jaimi edited the video recording of a previous record throw after discovering they were referred to as a “girl” in the footage.

“That piles up,” Jaimi said. “And it’s not right.”

Their frustrations extend beyond pronoun use. The very existence of separate men’s and women’s track and field teams makes the gender binary practically inescapable. Even though Stanford’s teams train together — a factor Jaimi found important in the recruitment process — the teams score separately in competitions.

Jaimi sees the binary as a product of society’s emphasis on winning.

“We kind of say, ‘I’m gonna suck it up; this is the way it is,’” they said, “because nobody’s really tried it any other way.”

Despite these frustrations, Jaimi competes, and at a high level. The thrower placed 10th in the discus at the 2018 Pac-12 Championships, and received an honorable mention for the Pac-12 All-Academic award. While Jaimi has continued to succeed in spite of a lack of gender inclusivity, other transgender athletes must sacrifice their careers in order to be themselves.

‘A trick of fate’

After just one year on the women’s lacrosse team, recruited goalie Shahpar “Shep” Mirza ’19 decided — with head coach Amy Bokker’s support — that it would be best to step away from the team.

Shep had already come out as a gay woman in high school. While growing up gay in the southern state of Georgia certainly required “a thick skin,” Shep said, teammates and coaches at Stanford were extremely supportive. Leaving the women’s lacrosse team wasn’t about that.

It was about Shep finding his identity as a transgender man.

As Shep emphasizes, the transition did not take place overnight. While he had openly identified as gay for years, he said it was around Thanksgiving break of his first quarter at Stanford that he cut his hair and began changing his gender presentation.

Even with these changes, though, Shep said he started “to realize that something was off” by the start of his second quarter, in January 2016.

He was still on the women’s lacrosse team.

He told Bokker about his concerns that month, and she helped him find a therapist in the athletic department. Therapy was of little help. Due to the therapist’s limited knowledge about the transgender community, she was ill-equipped to advise him, Shep said. He remembers teaching her concepts about transgender life, as opposed to the other way around.

Still, Shep “stuck it through” until the end of freshman year. Bokker told The Daily that, while she wanted to support Shep, she did not feel qualified or prepared for such a situation.

“I kind of followed his lead,” she said.

“By the end of it,” Shep said, “I think both my coach and I knew I wasn’t in a good headspace to continue playing, and she didn’t seem to have very hard feelings about it either.”

Even with Bokker’s support, Shep felt it was unfair to the team for himself — one of only two goalies at the time — to leave.

“I felt a lot of guilt with that for sure,” Shep said. “But I think it was ultimately the right decision for me.”

Stanford doesn’t have a varsity men’s lacrosse team, and Shep decided against men’s club lacrosse partly because of differences in rules and equipment. Men’s lacrosse, a contact sport requiring helmets and pads, was simply not the sport that Shep had grown up with.

Bokker pointed out that, since players of club sports do not receive athletic scholarships, transgender student-athletes at Stanford may suffer financially for transitioning. Beyond the financial concerns, Bokker said, there was “untapped potential” in Shep as a lacrosse player.

“[Shep] could have been an All-American goalkeeper,” she said, stressing that she would have loved to continue coaching Shep and “make it work.”

Under NCAA regulations, however, a a student-athlete undergoing a gender transition from female to male is no longer eligible to play for a women’s team. Athletes transitioning from male to female, meanwhile, are ineligible to play for a women’s team until after a year of “testosterone suppression treatment.”

While the policy is intended to limit the disparities in athletes’ bodily abilities, Jaimi criticized its implications for transgender athletes. They pointed out that the amount of testosterone in someone’s body is not the only factor that affects their athletic performance. Other natural features, like height among basketball players, can result in advantages regardless of one’s sex.

“If you’re a binary transgender person and you’re transitioning to your gender, you should be able to compete on the team you’re transitioning toward,” Jaimi said.

Stanford enforces its own eligibility requirements in accordance with these guidelines, wrote assistant athletic director of communications Brian Risso in an email to The Daily. The NCAA did not respond to The Daily’s request for comment.

“Stanford Athletics is committed to fostering an inclusive team environment for all students, including transgender athletes,” Risso wrote.

Shep is not ashamed of his history as a woman’s lacrosse player, nor of any other experiences he had in 18 years identifying as female. He emphasizes the salience of each step in his journey to become comfortable in his body, rather than focusing solely on his current gender identity.

“It’s kind of just who I was,” he said. “You looked different when you were 5 years old, too. Everyone grows into their bodies differently. I grew into a body on a different path than most other people take, but I’m super proud of that.”

From Bokker’s perspective, that path should not require giving up on a sports team.

“I just wish I had more answers as far as how he could have continued to be part of our team because I feel like being a student-athlete is such a valuable experience,” she said.

Among Stanford coaches, Bokker said, “There could be better training” regarding how to work with and include transgender athletes.

“It’s almost like penalizing them for a trick of fate that penalized them at birth,” Jaimi said of transgender athletes in general. “I don’t think that’s fair at all.”

‘What sport is all about’

It’s no secret that the world of sports fetishizes winning, from the ranking of countries by Olympic medals to the spectacles of championship bouts like the NFL’s Super Bowl. Replacing men’s and women’s sports divisions with all-gender alternatives, some argue, would significantly diminish the opportunity for women to experience winning and the empowerment it can foster.

“It gets down to what sport is all about,” Jaimi said, “and if it’s about winning, then you’re gonna want it to be separated by whatever strength capacity people have.”

Even among those who identify as female, women’s track athletes with naturally high testosterone levels due to difference of sexual development (DSD) are required by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) to undergo testosterone suppression treatment in order to compete in certain races at major competitions like the Olympics.

“The revised rules are not about cheating, no athlete with a DSD has cheated, they are about levelling the playing field to ensure fair and meaningful competition in the sport of athletics where success is determined by talent, dedication and hard work rather than other contributing factors,” said IAAF president Sebastian Coe on April 26, 2018, when the rules were announced.

South African runner Caster Semenya, who won the 2012 and 2016 Olympic gold medals in the 800-meter race, unsuccessfully challenged the new rules, and a group of researchers challenged the data on which the IAAF based its decisions. Despite instatement of the new rules on May 8, debate remains over the significance of testosterone in athletic fairness.

Regardless of how that debate ends, Jaimi doesn’t believe sport is about winning, certainly no more than it is about inclusion. And they hope others will come to that conclusion as well.

“It’s just a matter of being able to experience your body,” Jaimi said, “and everybody should glorify that because it’s fun.”

“Whether or not you get pushed off the podium, that doesn’t matter if you know your sense of accomplishment,” they added. “And the numbers, especially when it comes to athletics, they don’t lie.”

But the world of sport is not a meritocracy, and the numbers do not speak for countless other factors that contribute to a player’s ability to achieve. LGBT athletes have suffered through guilt and self-doubt about their mere presence on a team, facing concerns that they will negatively affect team culture and motivate backlash. Former SEC Defensive Player of the Year Michael Sam made little NFL headway after coming out as gay, struggling with a spotlight he never requested.

Jason Collins ’01 became the first active NBA player to identify publicly as gay when he signed with the Brooklyn Nets in 2014. But even he waited until he was away from Stanford and 12 years into his professional career to come out, noting that American culture was less accepting in his college days.

LGBT SportSafe Inclusion Program co-founder Nevin Caple visited Stanford on May 1 to offer guidance and reflect on her own experience playing women’s basketball at Fairleigh Dickinson University. Caple identifies as lesbian, and said she spent years struggling with the fear of coming out.

“When I was in college, we didn’t talk about what it meant to be LGBT,” Caple said.

But Caple’s concerns extended beyond her college playing career. She was a business student in college, and she said the negative perception of LGBT individuals in the sports community limited her career aspirations.

“I knew [coaching] wasn’t a place for a person like me in college athletics at that time,” she said.

The presence of any lesbian personalities on a women’s sports team, she added, fostered the misrepresentation of the entire group as a “lesbian team.” Whereas gay men are commonly ostracized by men’s sports teams, women have been stereotyped as lesbians, Caple noted. Neither perception is fair.

“[Such misconceptions] would force people into an apologetic stance about their femininity, their athleticism and, ultimately, their sexuality,” Caple said.

For transgender athletes, there is a logistical challenge in crossing the sports gender divide. And then there are similar concerns to those faced by Sam, Collins and Caple, concerns of team culture, fan culture and acceptance. To single out trans athletes for supposed genetic advantages is wrong, Jaimi said, when there are so many “other stressors that go into being a human being.”

Mental health is just one factor, but one with major consequences. The American Academy of Pediatrics found in 2018 that rates of attempted suicide among transgender adolescents aged 11 to 19 were multiple times higher than among those who were cisgender.

While 9.8 percent of cisgender males and 17.6 percent of cisgender females observed in the study had attempted suicide, the rates soared to 50.8 percent among transgender males and 29.9 percent among transgender females. The rate was 41.8 percent among adolescents identifying as non-binary, and 27.9 percent among adolescents questioning their gender identity. Jaimi attributed these disparities to exclusion of and discrimination against transgender individuals.

“Recognizing trans kids is suicide prevention,” Jaimi said.

When athletes are consistently sorted and evaluated among two genders, however, recognition is nonexistent.

A necessary evil?

For Jaimi, who does not identify as a man or woman, playing on a women’s team is the best option for them to compete, given Stanford does not have an all-gender team. Whereas athletes are usually restricted to either a men’s or women’s team, Jaimi said, gender “is never black or white — it’s very colorful.”

There have been steps to make teams more accepting of transgender athletes, and while Jaimi feels safe in their identity at Stanford, they said there will never be full acceptance so long as sports remain gendered as they are today.

Jaimi does not know what a non-gendered athletic world would look like, especially with regard to competition. But they aren’t alone in trying to envision one.

“I feel like we all need to invest a little bit more in making it an inclusive space, and changing the culture of sport and really evaluating what sport is about,” Jaimi said. “I think we don’t have consensus on that, and so that makes it difficult to make changes, specifically in regulation.”

When it comes to acknowledging their pronouns, Jaimi sees no excuse for the errors that continue to occur.

“I would hope that eventually we get to that point,” Jaimi said. “I would hope that eventually means in the next two years.”

Jaimi criticized society for approaching gender inclusivity with a “baby step mentality,” one which they have observed even at Stanford. They suggested that the University instill gender inclusivity training for officials who oversee competitions involving Stanford athletes.

Though there is more work to be done, Jaimi said they are immensely grateful for Stanford’s existing support systems and the generally accepting atmosphere of Stanford Athletics. They stressed that not all members of Stanford’s trans community feel the same.

“If I couldn’t exist in this space and be who I am — it would not matter — I would not be here,” Jaimi said.

While he is also appreciative of the Stanford community, Shep said it is important to continue holding the University to a high standard to “see where we can push it.” Improved gender inclusion training and all-gender athletics opportunities are just two potential measures.

“The West Coast starts off with a lot of policies that shift the rest of the culture of America,” Shep said. “And so, how can we do that in a microcosm of Stanford? How can we set an example for other universities around the country?”

‘A new Title IX’

As for how gender-inclusive, competitive athletics would look across the board — players, coaches and administrators alike remain undecided.

“I don’t have an answer to that,” Bokker said. “But I do think it should be addressed.”

While studying at George Mason University, Bokker wrote her thesis on Title IX, which dramatically increased women’s access to sports after it was passed as part of the Education Amendments of 1972.

Title IX states that, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Similar action may need to be taken, Bokker said, to facilitate transgender inclusivity in sports today. A hypothetical update or supplement to Title IX could extend the inclusion to people of all genders.

“Maybe this is a new Title IX,” Bokker said of potential legislation requiring transgender inclusion. “That was opportunity for women. Maybe this is opportunity for transgender [people].”

While Stanford defers to the NCAA for questions of athletic eligibility, Shep and Jaimi emphasized the University’s relatively high inclusivity. As an athletics representative, Risso said the department “strives to be an industry pioneer and trusted advocate as it relates to generating awareness of all student-athlete issues,” and “took tremendous pride” in sharing Jaimi’s story.

Bokker echoed these sentiments, but acknowledged the limitations of her knowledge and power to promote gender inclusivity as a coach.

“I felt like, to be at any school, I was really glad [Shep and I] were at Stanford,” Bokker said, “because I think Stanford is a great place as far as having resources and getting good direction … but I definitely wish I was better equipped [to help].”

Athletics are just one space where full gender inclusivity remains unattained, even at Stanford. As a resident assistant at Stanford’s Outdoor House residence, Shep works toward inclusivity in the outdoor community, which — similarly to sports — has been criticized for gender and racial exclusivity. After The New York Times reported that the Trump administration was “considering a legal definition of gender as immutable and fixed at birth,” Shep said he was devastated.

“I remember just feeling so sad and defeated that day,” Shep said. “And I have this trans flag, I … put it out on the breezeway of Outdoor House. And it’s stayed there ever since … out there in front of our door.”

“It’s just really nice to reclaim a space,” he added.

As trans individuals reclaim other spaces that have long operated under the gender binary, athletics could be next. But Jaimi and Shep agree that changing a deeply ingrained athletic system will take time.

“I’m not a fool,” Jaimi said. “I know that it’s a gendered world.”

But as Jaimi sees it, gender is a social construct, and one that — like other identities — is no grounds for segregation in sports. When it comes to testosterone levels and other sex differences, Jaimi doesn’t understand fairness concerns, especially when 7-foot basketball players have been eligible and played in professional men’s and women’s leagues.

“Team sports magnifies the smallness of it,” Jaimi said.

Though they acknowledged there are legitimate differences in capacity among track and field athletes of different sexes, Jaimi draws a line between the right to win and the right to play. And they maintain that anyone transitioning between genders should not be sidelined because of it.

“I don’t think [gender identity] should be punished at all,” Jaimi said. “But that is the reality as of right now. It can change, and it should change.”

Contact Holden Foreman at hs4man21 ‘at’ stanford.edu.