“What the fuck did we just do?” Sophia Sterling-Angus ’19 remembered thinking to herself, staring at the numbers on her laptop screen last fall.

13 hours prior, she and Liam McGregor ’20 sent a survey called the “Stanford Marriage Pact” to around 10 Stanford email lists and group chats. Questions poked shamelessly at students’ intimate values, ranging from “How kinky do you like your sex?” to “Are you comfortable with your child being gay?”

The goal was lofty: finding each participant a future spouse. Ultimately, an algorithm for stable marriages would filter through the profiles and find each student their most compatible long-term partner — a “backup plan” in case both people end up single later in life.

Like many entrepreneurial fairy tales, the idea began with a white board — inspired by an economics homework question referencing the Nobel Prize-winning stable marriage algorithm, coupled with observations of Stanford’s dating scene.

“We [the Marriage Pact] have this joking voice where we are like, ‘When you look up in 10 years, there will be no good people left for you.’” McGregor said. “…Students are focused on academics and finding a job, but they’re also in the best place they’ll ever be to find someone to marry. And they may not find someone.”

The best-case scenario would have been to have a hundred participants, Sterling-Angus recalled thinking at the time. After all, “take my survey” pleas constantly clog student email inboxes, earning them a brand of disdain reserved for things like fruit flies and annoying slang. Most go straight to the Trash folder.

Yet, half a day later, in mid-November 2017, Sterling-Angus opened the Stanford Marriage Pact form to find over a thousand responses. Within five days, they had hit over 4,000 responses — over half the undergraduate population. Sterling-Angus and McGregor found themselves in possession of a highly personal dataset on students’ relationship views, substance use values and political, sexual and religious preferences, all identifiable by name and without any privacy agreement.

The algorithm’s 2017 matches sparked thousands of awkward Facebook messages, hundreds of dates and even a handful of lasting relationships, according to feedback results from last year’s experiment. By 2018, the Marriage Pact had quickly escalated from a mysterious Typeform link to a near universally-recognized term on campus. This year’s Marriage Pact 2.0 was even bigger and better-researched, with a pool of 4,465 students largely representative of Stanford’s undergraduate demographics.

Data privacy debates now extend from Hewlett-Packard to the Hill — a tech industry tailspin fueled by incidents like Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal and Google’s Gmail data sharing controversy. This year, McGregor and Sterling-Angus also made upgrades to the Marriage Pact’s data policy. Namely, they created one in the first place.

“The truth is that there is some relatively sensitive data involved in here,” McGregor said.

Policies include a promise not to sell data, conceal individually identifiable data and offer contact information only to your match. For each participant, the Marriage Pact obtains four types of data: demographics, contact information, values and the relative importance of your values.

“[Popular dating app] Tinder does a really good job with pictures and two sentences, which optimizes one-night stands,” Sterling-Angus said. “But when you go from five days to five months to five weeks to five decades, we thought we needed something else…. a common set of values. A common approach to life.”

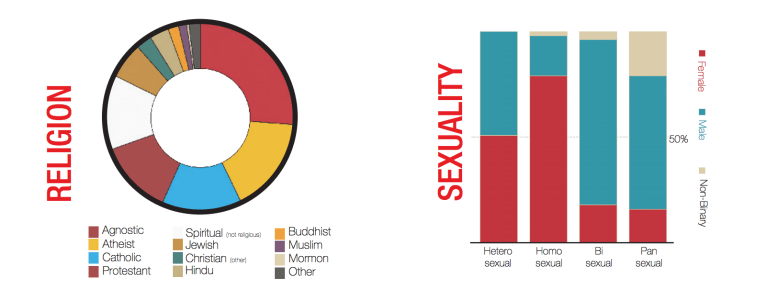

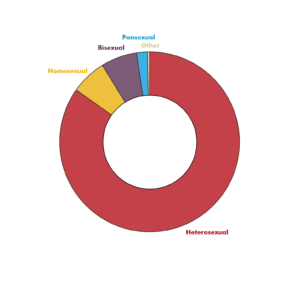

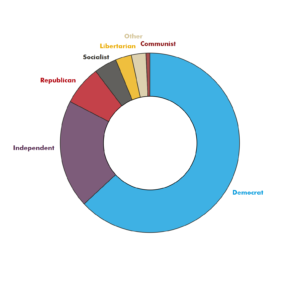

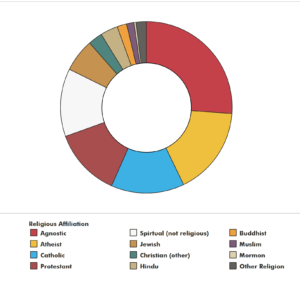

The resultant data pool — obtained and visualized in anonymized form by The Daily’s investigative team — provides unique insight into the Stanford psyche. For example, men were more likely to view themselves as smarter than most people at Stanford, while women reported themselves as average or below the average. Forty-eight percent of students expect their children to attend Ivy League colleges, while 83 percent of students think abortion should “always be legal.” Demographics analysis showed that the majority of people who identify as homosexual are men, whereas bisexuality is dominated by women.

Despite the Marriage Pact’s implied fictionality, Sterling-Angus and McGregor see algorithmic matching based on this type of data as a future reality.

“It takes such hubris to say, ‘Just by my own searching, I found the best person to marry,’” McGregor said. “…It’s very hard to search through a relevant number of people and judge them on their qualities. This is the chance to officially search thousands of people.”

“How many couples do you know met on Bumble or met on Tinder?” Sterling-Angus added. “I think it’s not a bad thing to increase your optionality and meet people who you otherwise wouldn’t have…. Before, we were really limited to people that you naturally come across — and technology allows you to expand that circle.”

The Marriage Pact feedback form includes success stories of Memorial Church makeouts, relationship sparks and budding crushes. Stanford alumni and San Francisco residents have even reached out to the Marriage Pact administration email asking for a marriage pact for their respective pools — perhaps one with a less joking tone.

“One marriage,” Sterling-Angus said with a mischievous shrug. “I want one marriage.”

Contact Kit Ramgopal at kramgopa ‘at’ stanford.edu.