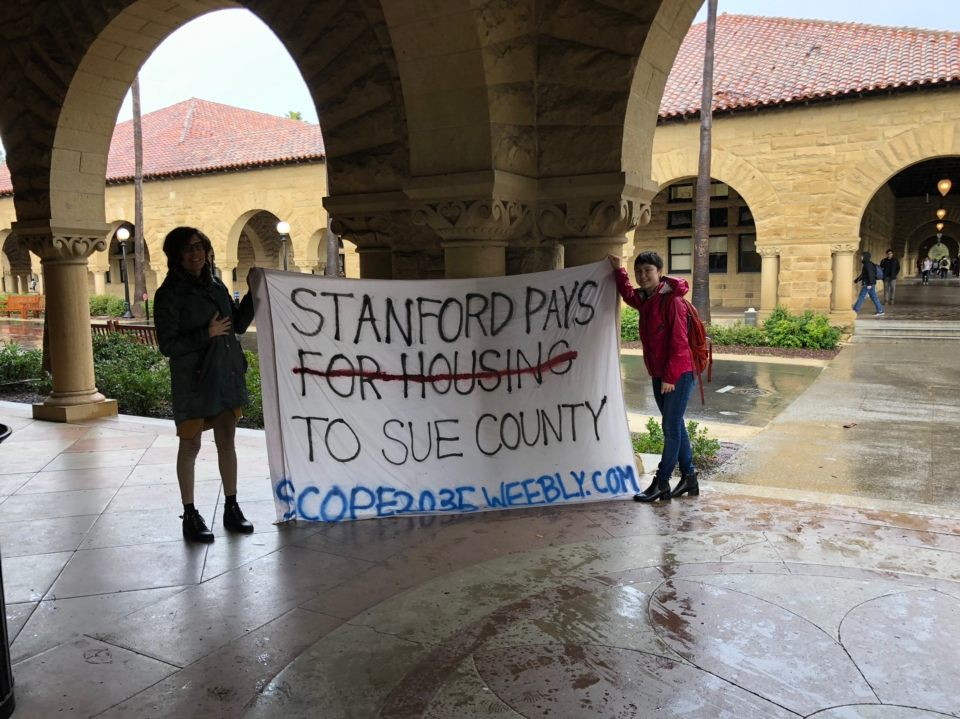

The Stanford Coalition for Planning an Equitable 2035 (SCoPE 2035) held several demonstrations across campus on Thursday to protest Stanford’s lawsuit against Santa Clara County’s housing ordinance. From White Plaza to Main Quad to Columbae, members of SCoPE 2035 and workers from the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 2007 held up large banners criticizing Stanford for “paying to sue” the County rather than house its workers.

The lawsuit in question was filed in state and federal court on Dec. 20, 2018 by the University’s Board of Trustees against Santa Clara County for its Inclusionary Housing Ordinance, which would require 16 percent of Stanford’s planned housing units to satisfy certain affordable housing specifications.

In its complaint, the University argues that the County’s ordinances violate the Equal Protection clauses of the United States and California Constitutions and “impermissibly target” Stanford to address a longstanding countywide affordable housing problem that “all new housing development” in the County’s jurisdiction — not just Stanford’s — contributes to.

“The issue in the litigation is not about Stanford’s commitment to more affordable housing, but rather that it is unlawful for Stanford to be singled out for unequal treatment in a county ordinance,” wrote University spokesperson EJ Miranda in an email to The Daily.

However, SCoPE 2035 stated in a public Facebook post preceding the protests that the University was “misrepresenting the facts.” According to the student organization, the lawsuits were an important step in ensuring that Stanford mitigates the “harmful effects” of its continued expansion on workers’ commute times, housing affordability and sustainability.

While the lawsuit motivated this particular protest, SCoPE 2035 looks to address the effects of the expansion plan detailed in Stanford’s General Use Permit (GUP) application on sustainability and worker’s rights at large, SCoPE 2035 media team head Shelby Parks ’19 said.

The GUP, a land use agreement between the County and Stanford, would allow the University to construct 2.275 million square feet of new academic facilities and 3,150 on-campus housing units by 2035 if approved by the County Board of Supervisors this June.

The University’s plans have received pushback from the County, the Palo Alto community and school board, union workers on campus and student groups. The University has held several community forums and open houses along with other engagement initiatives aimed at receiving input from community stakeholders. Miranda told The Daily that in July 2018, Stanford submitted a new affordable housing offer to the County that was “responsive to feedback from county supervisors and community members.”

Miranda emphasized that the lawsuit addresses the constitutionality of the County’s housing ordinance only applying to Stanford, and is not an indication of their support for affordable housing.

“Stanford recognizes the critical affordable housing challenges in our region, which is why the university is a major supporter and developer of affordable housing, and is a leader in Santa Clara County in this respect,” Miranda wrote.

In addition to the additional on-campus housing, Stanford is bringing 1,300 more affordable housing units to campus through the Escondido Village Graduate Residences project, and has contributed $26 million to Santa Clara County’s affordable housing fund since the 2000 GUP. The current GUP allocates $56 million more for local affordable housing projects.

According to SCoPE 2035, this is not enough to account for the predicted 7,509 new students, postdocs, faculty and staff that will come with Stanford’s expansion. Specifically, protesters feel that the GUP does not adequately address the lack of affordable on- and off-campus housing for Stanford’s employees or the increased traffic and commute time for many of these employees.

“The high cost of living in this area means that [members of SEIU] are trying to make ends meet,” wrote Francisco Preciado, SEIU Local 2007’s executive director, in a statement to The Daily. “Many of our members are working multiple jobs and commuting long distances because that’s the only way they can afford to take care of their families.”

These commutes, in turn, create smog and contribute to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, in addition to the GHGs emitted by the new academic facilities to be constructed. The final environmental impact report (EIR), released by the County in December of 2018, confirmed that total GHG emissions under the GUP would meet state reduction guidelines for 2030 and 2050, though these calculations were contested by SCoPE 2035 in their February 2018 comment package to the County Department of Planning and Development.

SCoPE 2035 is planning to host several teach-ins in the next two weeks to address housing affordability and workers’ rights preceding the final stages of the GUP negotiation set to occur in 2019.

“It’s easy to see Stanford as this sunny utopia but a lot of hard work goes into maintaining our lawns, cleaning our bathrooms, and making our food,” Parks said. “Our university’s most fundamental operations depend on workers and they should be treated better.”

Daniel Yang contributed to this report.

Contact Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The article has been corrected to show that there is only one suit filed by Stanford in federal and state court challenging the same inclusionary housing ordinance, and no second suit challenging the affordable housing impact fee ordinance. The Daily regrets this error.