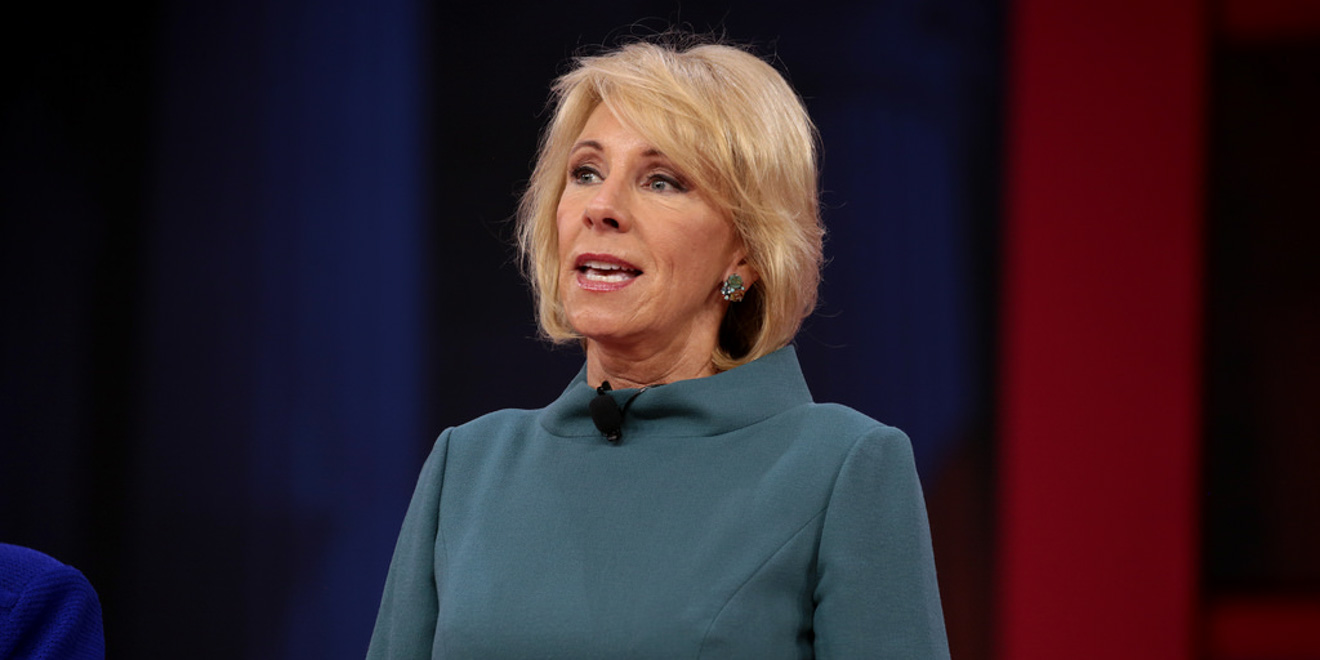

If adopted, U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’ proposed changes to federal guidance on colleges’ sexual assault policies would likely require Stanford to revise several key aspects of its Title IX system, according to an analysis by the University’s Office of Institutional Equity and Access.

Potential changes include narrowing the scope of allegations Stanford can investigate under Title IX; modifying hearing procedures and adding hearings for claims against non-student community members; and making the University review its burden of proof as well as the interim measures it provides in sexual assault cases.

Many schools have grappled with uncertainty over the future of their Title IX programs since DeVos announced her intentions to overhaul federal policy. The Office of Institutional Equity and Access’ Jan. 8 analysis, created at the request of Associated Student of Stanford University (ASSU) Executives Shanta Katipamula ’19 and Ph.D. candidate Rosie Nelson, gives a “high-level overview” of changes Stanford might need to make if DeVos’s plans move forward. At the same time, it notes areas where the precise impact of DeVos’s agenda remains unclear.

In a “Notes from the Quad” blog post released shortly after DeVos unveiled her plans, Provost Persis Drell emphasized that “nothing changes today in our campus Title IX procedures as a result of this development.” University spokesperson E.J. Miranda told The Daily that Stanford is working to submit comment through the Association of American Universities, as Drell said it would in her blog post.

DeVos released her proposal for Title IX in November, and the Department of Education is accepting comment on the plans until Jan. 28. Last week, both the undergraduate and graduate bodies of student government approved a bill to submit comment on behalf of the ASSU. The ASSU’s input for DeVos is highly critical of changes that it says would deter sexual assault victims from reporting and undermine Stanford’s ability to keep its campus safe.

Longtime critics of Title IX, in contrast, see DeVos’ proposals as making colleges’ handling of sexual assault claims fairer to the accused.

Ph.D. candidate Emma Tsurkov, the ASSU Executive’s Co-Director of Sexual Violence Prevention, said the Office of Institutional Equity and Access’ analysis was “pretty much consistent with what we expected.” While she worries about the impact DeVos’ proposed changes could have at Stanford for victims of sexual assault, she was encouraged by students’ interest in providing Department of Education with their feedback.

“We did tabling at White Plaza for three days, we had a workshop, we sent the [ASSU] bill for people to give comments on … So I think overall the amount of students we’ve engaged with is probably in the hundreds,” Tsurkov said.

Potential changes

Almost all of the Department of Education’s proposed changes are opposed by the ASSU.

Stanford might have to revise its definitions of sexual harassment, the analysis states. For example, the new rules would prevent the school’s grievance processes from handling allegations of harassment that did not take place within a Stanford program or activity.

However, the analysis notes that Stanford could use other University policies — like the Fundamental Standard for students and the Code of Conduct for community members more broadly — to address behavior that would move outside Title IX’s jurisdiction under new rules.

Stanford may also have to provide hearings for Title IX complaints against any University community member — right now, it only provides them for claims against students — and add video technology to its hearings so that parties can see each other during the proceedings, rather than just listen in.

University processes would need to allow the complainant or accused’s support person to directly question the other party in the case, as well as their witnesses. Stanford’s existing student Title IX process allows each party to submit questions through a hearing panel.

For Tsurkov, the ability to more directly cross-examine is one of DeVos’ most concerning proposals.

“Having due process doesn’t mean retraumatizing victims,” she said, arguing that “there’s nothing that would hurt the discovery of the truth if it’s not done directly [but] through a panel.”

Bob Ottilie ’77, a defense lawyer who has represented Stanford students and has been critical of the University’s Title IX processes, also noted the significance of the cross examination proposal, calling it “huge.” Unlike Tsurkov, though, he approves.

“Sometimes I’ll go 40 minutes into some area that I start with cross-examination,” he said. “It’s the ability to pursue [people] with a series of questions … If it’s implemented it will make a huge difference in the outcome of these cases.”

The analysis also states that Stanford may need to “review” its evidentiary practices in Title IX cases, but does not elaborate.

Stanford uses a third-party “evidentiary specialist” to look over what Title IX investigators have gathered in a case and decide what can go before panel members. Parties can argue to the specialist for the inclusion or exclusion of certain information, but for the purposes of the hearing they must stick to evidence the specialist admitted.

DeVos’s rules would instruct schools to provide all the evidence they have gathered to the parties in a case. While Stanford has stated publicly that it shows parties all evidence collected and redacts only minimal personal information like names or Social Security numbers, Ottilie has shown The Daily correspondence with Title IX staff indicating more extensive redactions. Ottilie said his clients couldn’t argue for the information’s inclusion because they did not know its substance.

The Department of Education’s proposal further states that all the evidence schools collect must be available to parties as a hearing proceeds “to give each party equal opportunity to refer to such evidence during the hearing.”

Victims’ advocates have expressed concerns about the implications for students’ privacy and victims’ willingness to go through Title IX proceedings as a result.

Tsurkov highlighted use of evidence as another part of DeVos’ plans that particularly troubles her. Title IX investigations by nature involve sensitive personal material, she said, and information gathered that’s irrelevant to the charge at hand should not be fair game for parties to use.

“The chilling effect of not reporting because the cost might be that your entire private life becomes available to the person who assaulted you is horrifying,” Tsurkov said.

Unknown impacts

The potential effects of DeVos’s rules are murky when it comes to Stanford’s standard of proof necessary to find guilt in sexual assault cases. The proposed federal regulations would allow schools to use either the higher “clear and convincing evidence” standard or the lower “preponderance of evidence” standard used in civil courts, which the Obama-era Department of Education told all colleges to adopt. But colleges would only be allowed to use “preponderance of evidence” for Title IX matters if they do the same for “conduct code violations that do not involve sexual harassment but carry the same maximum disciplinary sanction.”

At Stanford, other student conduct violations like cheating can lead to suspension or expulsion — the default sanction for sexual assault, although Stanford data shows that no Title IX cases over the last two academic years have led to expulsion. But student conduct violations outside the scope of Title IX are adjudicated under the highest standard of proof, the “beyond a reasonable doubt” bar used in criminal court.

Meanwhile, California law clashes with DeVos’s proposal by requiring universities to use preponderance of evidence for Title IX cases.

For all these reasons, “it is not yet clear” how DeVos’s regulations could play out at Stanford, the Office of Institutional Equity and Access’ analysis says.

However, the analysis also notes that Stanford might have to revise its policies to state “presumption of innocence” for the accused. The Judicial Charter — which governs student conduct investigations outside of Title IX — presumes innocence, the analysis states, but Title IX policy avoids this language, providing instead for neutral panelists “who will not prejudge the outcome of a case because there has been a charge.”

The analysis also describes “unknown” effects for new federal guidance on “support measures” such as no-contact orders meant to help victims of sexual assault feel safe on campus. The proposed new federal regulations would allow schools to give support measures without a formal process like a hearing, but these measures could not be “punitive or disciplinary.” No-contact orders would have to be mutual.

The analysis says that Stanford might need to change its policies on “interim measures” provided to complainants while a Title IX investigation pends, but does not give details. Interim measures can range from no-contacts to moving accused students to different housing or requiring them to attend classes with a security guard.

The ASSU’s feedback to DeVos, however, projects more specific consequences of the proposed policy change.

“Survivors awaiting the resolution of their complaint who wish to not be in contact with their assailant will have to change their own academic and extracurricular schedule, housing and dining,” reads the ASSU statement, which was drafted by Katipamula and Tsurkov. “Forcing the victims of assault to be the ones who have to move will create a significant barrier to reporting.”

Advocates for the accused, meanwhile, have taken issue with measures they say infringe too much on someone who has not been found guilty.

“That’s a great big scarlet letter that says you are an accused rapist,” defense lawyer Ottilie said previously of security guards as an interim measure.

Katipamula told The Daily she plans to publicize the Office of Institutional Equity and Access’ analysis soon in an email to campus community members.

Contact Hannah Knowles at hknowles ‘at’ stanford.edu.