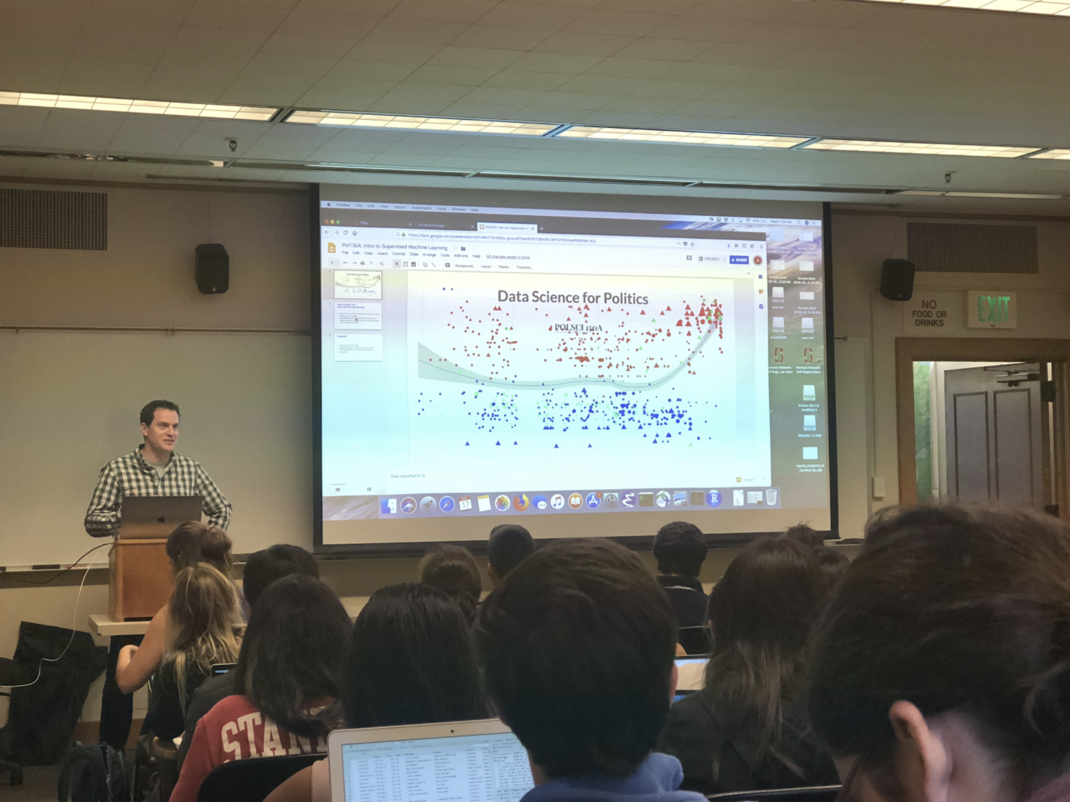

In POLISCI 150A: “Data Science for Politics,” political science associate professor Adam Bonica uses a project-based curriculum to allow students to explore data-driven predictions in modern politics.

With the programming language R, the class’ approximately 50 students tackle problem sets in teams. For example, the most recent problem set challenged each team to find new predictive variables to add to a shared dataset used to make predictions about the midterm elections. The midterm assignment for the class is to predict the 435 House of Representatives seats in the midterm elections.

Bonica has been collecting data with which to forecast congressional elections for years, and he uses his expertise to guide students in improving forecasting models with unconventional datasets.

After the midterm elections, students will write an op-ed in which they present their data analysis about a relevant political topic, followed by commentary, similar to a piece that would appear on the statistics website FiveThirtyEight. Bonica hopes that his students will eventually have the opportunity to submit their op-eds to publications outside of the University.

This is Bonica’s first year teaching the class, which he adapted from POLISCI 358, a data-driven politics course that he already teaches to graduate students. Inspired by his brother, a high-school teacher, Bonica aims to use guided projects and independent research to allow students to develop skills that they could not learn in a traditional class.

“It’s really about learning how to navigate the whole process [of mining and analyzing data], with new information appearing every week,” Bonica said.

The interdisciplinary approach of the class appeals to students with a broad range of interests and backgrounds, ranging from programmers looking to analyze rich datasets to those interested in politics who want to enhance their ability to work with data.

Nik Marda ’21, who is double-majoring in computer science and political science, said he enjoys the interesting datasets that Bonica introduces to the class, and particularly enjoys how current events are incorporated into coursework. For example, the class recently analyzed American Bar Association rankings in light of the debate surrounding Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination.

“We really got to do objective, non-partisan analysis during a very partisan debate,” Marda said.

Sarah Maung ’21 says that she enrolled in the class with minimal programming experience but that she loves how the class teaches students to use data for political forecasting.

“I am amazed by the potential of data to unearth obscure yet crucial insights in the realm of politics,” she said.

Bonica also incorporates his personal research into the class. For example, while introducing a dataset on political candidates that included a column on whether the candidate was a lawyer or not, Bonica pointed out his own finding that 58 percent of Senate members and 42 percent of House members are lawyers, and that this number was previously as high as 85 percent across Congress.

Bonica said he wants his students to understand how to handle interesting political datasets, but most importantly, he wants to show them the power inherent in data itself.

“I want my students to appreciate how powerful good data can be in getting a glimpse into where politics is heading,” Bonica said. “Data has informed politics for decades.”

Contact Yash Pershad at ypershad ‘at’ stanford.edu.