Works of art can bring us closer to other people, raise questions that make us examine our values and opinions and articulate emotions and thoughts we’ve had but have never expressed. Perhaps the most resonant artworks are those that give us a new framework for experiencing the world. Art can draw our attention and appreciation to aspects of life that never drew us in before, and through this process, pieces of art become a part of us and our experience.

Visual art is one such example. I recently took a trip to SFMOMA’s exhibition on Rene Magritte. I came in searching, as I generally do, for the philosophical, abstractable ideas contained within Magritte – the treachery and deceitful nature of images, art itself immersed in the world it is trying to depict, the anonymity and changeability of the artist. That’s why I have always viewed Magritte’s art as particularly valuable – he makes interesting, skillful paintings that are fun to look at but even more fun to contemplate. Yet, by approaching his work through the mindset of thinking, I was missing out on an enormous portion of what Magritte and the medium of painting can convey.

My friends who are visual artists would often spend 10 minutes in front of a Magritte painting, debating the significance behind a particular shade of green, arguing whether a lion’s paws were face up or face down or whether the moon was waxing or waning. These details pass me by constantly in my daily life, and even those in visual art do not evoke much contemplation. The moon is waxing because it is, I think to myself, and reading into it more is a fruitless endeavor. But that’s not quite true.

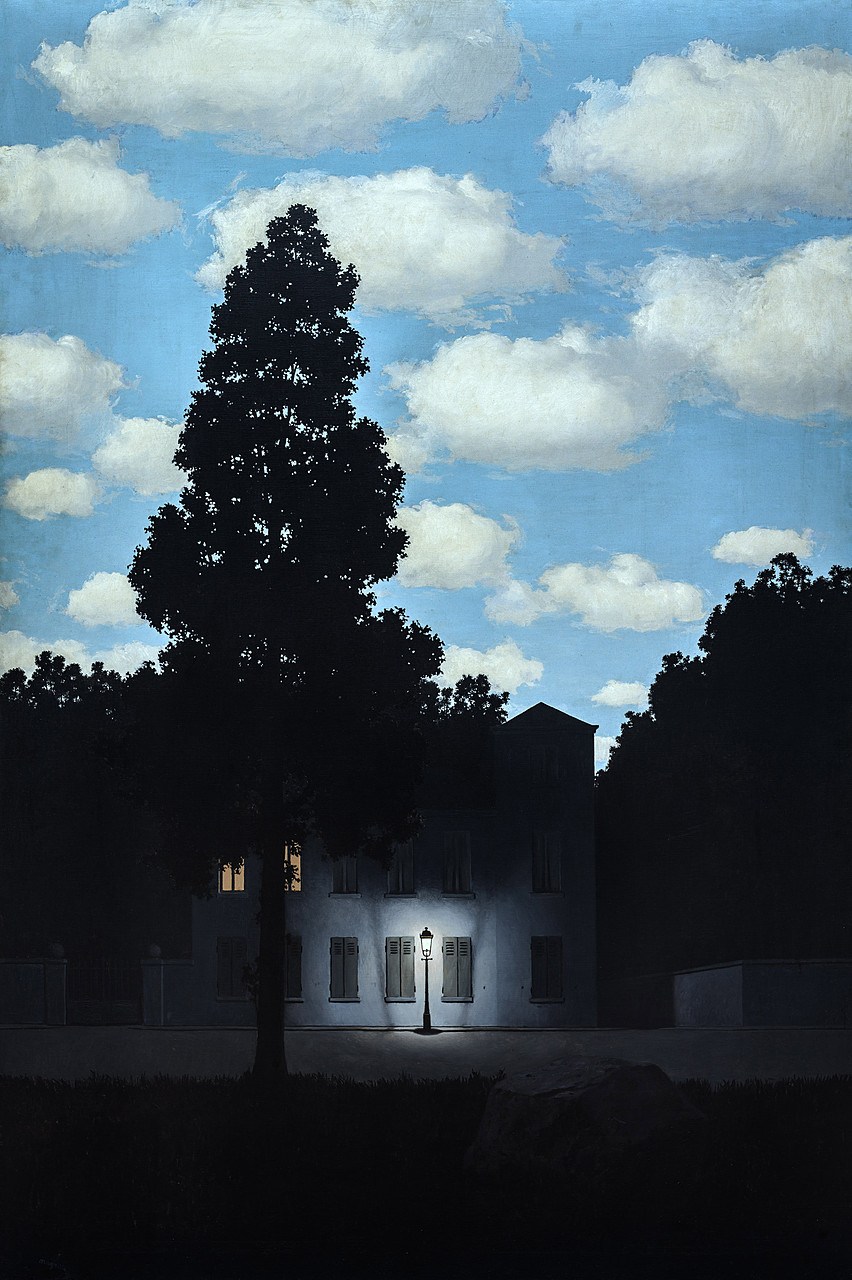

As part of my visit, I walked through a gallery with a series of paintings of houses. The houses and the streets in front of them were dark and lamp-lit like it was night time, but the skies above them were bright blue with fluffy white clouds. Thus, the images were subtly disorienting and surreal, filled with Magritte’s intrigue with evocative juxtaposition. I listened to my friends point out the shadows and lack thereof on each of the street lamps in the paintings. Shadows are an aspect of the physical world I’ve tuned out entirely, because they are just there where they should be, whether I wish it so or not. But this mindset shows precisely why I would miss the significance of the lack of a shadow or the wrong shadow, which can hold all the significance in the world to someone who makes their artistic statements entirely through a visual medium.

Writing is the most familiar art form for me, both to consume and produce, and I fully believe that writers are deliberate about every word they use, imbuing each one with as much meaning as possible to precisely articulate their ideas or convey a sensation. So why would this not extend to visual art? A painter only has the paint on the canvas as their means for conveying the nuances of human thoughts, emotions and experiences. In service of this goal, why wouldn’t they carefully choose every color, shadow and shape to reflect whatever facet of existence they are trying to convey?

Reading “Fragments of Sappho,” a collection of ancient Greek lyric poetry on the nature of love, brought these same ideas to mind. Most of Sappho’s poetry has been lost and damaged over the millennia, so we only have tiny portions remaining – single words, enigmatic phrases, occasionally a few stanzas. There is almost no way to discern the full story behind such evocative but isolated lines as “i don’t know what to do / two states of mind in me” and “do i still long for my virginity?”, but inexplicably the words still make us feel deep and nuanced emotions. In a sense, we don’t want or need to know the rest, because the lack of context gives Sappho a distinct allure, as we have so much space to find ourselves within the sparse words and infuse them with our own personal meaning. Our attention is drawn to the innate beauty in words and phrases like “gold anklebone cups,” “radiant lyre” and even “celery.” Sappho is not meant to be only studied – she is meant to be experienced.

Sappho revealed to me something critical about writing – words can have a weight not necessarily connected to their objective meaning. So when a strangely magnetic phrase comes into my head, I write it down as quickly as I can. Someday, I may come back to it and let it guide me to something more, but I can also just leave it as it is, a fragment, and that is art as well. This is similar to what Magritte taught me about art in visual forms – images are alive, and whether they portray an external or internal experience, they are full of subjective weight and meaning. If we think a certain shade of green is indicative of something, this is not over-analysis – the exact purpose of art is get us to make these unique associations that are both entirely subjective and meticulously evoked by the artist. It doesn’t mean that the artist necessarily had in mind what you have in mind, or that the artist had anything particular in mind at all. The mere act of conjuring something within you, as a response to an artwork external to you, is where the magic lies for both the artist and the audience.

This new mindset is hard to enact day to day – the physical world, especially that of routine, so easily dissolves into background like white noise. But taking time to consciously pay attention to the world, as if one were Magritte or Sappho, can make life so refreshing. Look at ordinary things and people, hear simple words and relish the sense of the sublime they evoke in you – all of which are impossible to explain, but encapsulate the value of just being alive.

Contact Carly Taylor at carly505 ‘at’ stanford.edu.