“Why do you put a case on your iPhone, but not a helmet on your head?”

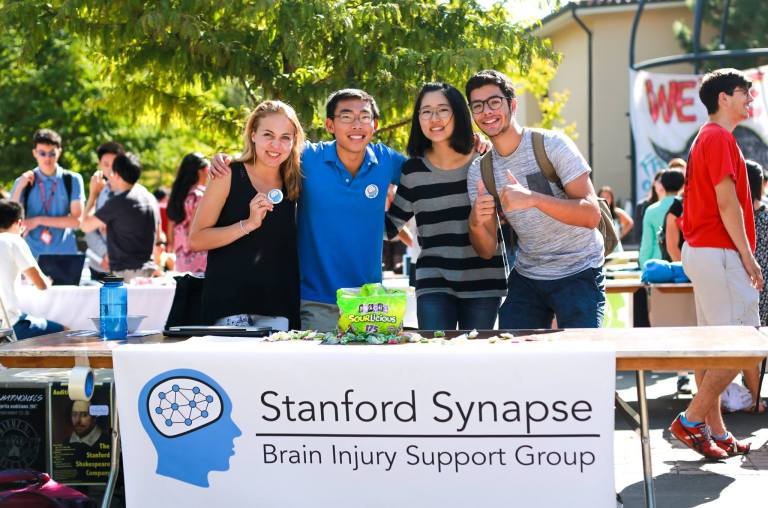

Members of Stanford Synapse, a brain injury support group, like to ask this question to students biking on campus without head protection.

“If you crash and hit your head, it’s going to cost you a lot more than [the cost of an iPhone] and a lot longer to get it fixed,” cautioned Brett Bullington, a member of Synapse and survivor of traumatic brain injury. “The brain is a fragile thing.”

In Oct. 2012, Bullington — a long-time Silicon Valley advisor and investor — embarked on an ambitious cross-country bike ride to raise money for charity. But while going downhill on an Oklahoma highway, he lost control of his bike and crashed into the ground face-first. He was rushed by helicopter to a hospital, where he was comatose for nine days.

Synapse provides peer support to individuals on campus and from the mid-Peninsula area who, like Bullington, have suffered a brain injury.

“Our goals are twofold,” said Michael Chen ’18, the president and founder of Stanford Synapse. “Providing support to the community and being advocates for them, as well as developing the next generation of leaders in healthcare and medicine.”

Brain injuries vary in scope from mild to severe. But however traumatic the injury is, the process of recovering from surgery, rebuilding relationships and returning to academic or professional life creates many challenges.

“It can change who you are,” said Alessandra Marcone ’20, the group’s vice president of outreach, about brain injury. “One of our members said, ‘I had to give old Jason away and realize who new Jason is and be happy with that.’”

To support individuals in this recovery process, Synapse runs peer support group meetings every other week, as well as a buddy program and social events. They also hold public lectures from medical professionals to raise awareness of brain injuries and medical advances in the field.

Providing support

Chen founded Stanford Synapse in his freshman year — alongside Stanford Medicine students Alissa Totman and Jaclyn Konopka — after he noticed how few Stanford students wore helmets, risking damage to what he regarded as their most precious asset: their brains.

Witnessing a catastrophic bike accident that same year also inspired Chen’s to support individuals living with brain injuries.

“People with brain injuries tend to feel really isolated,” he said. “You can’t do a lot of the things you would normally do; for instance, playing sports … People suffer from headaches, migraines, trouble concentrating — there’s a whole host of symptoms — so people need support.”

Since the group’s founding, its patient population has grown, and it now serves around 20 individuals at its fortnightly peer support group meetings. According to Marcone, most attendees are from the local community, and only a handful are Stanford students.

The peer support group, led by Isabel Goronzy ’18, aims to foster community amongst individuals with brain injury, their caregivers and student peer supporters. The confidential meetings, directed by trained student moderators, give members an opportunity to share their personal struggles and successes living with a brain injury or taking care of someone who does.

“Looking back, if I had a support group like the one we direct at Synapse, it would have been really helpful for me emotionally and helped me validate my symptoms,” said Marcone, who suffered a brain injury while playing soccer during her junior year of high school.

Chen agreed that suffering from a brain injury, unlike from a broken arm, can feel like having an “invisible illness.” He emphasized the value of individuals sharing experiences while they adjust to life post-brain injury.

“People who are relatively farther along in their recovery are very valuable resources for people not as far along,” Chen said, adding that members often trade strategies and recommend speech therapists and practitioners to one another.

Some of the meetings are run as workshops revolving around a theme related to the recovery process: for example, navigating the healthcare system. Students moderate a discussion and members share their experiences and offer advice to one another.

During their training, peer supporters learn about brain injuries and techniques to provide empathy, create a non-judgmental space and facilitate positive discussion. According to Chen, the group receives training advice and support from its faculty advisors, including Associate Dean of Students Alejandro Martinez and Clinical Professor of Neurosurgery Jamshid Ghajar.

Nevertheless, Marcone said that most of the learning about how to run the group comes from being sensitive and perceptive.

“It’s really just being there for people, which is more of a human skill than a classroom skill,” she said, adding that empathy can come quite easily. “Hearing people’s stories is really powerful.”

In addition to the peer support group meetings, Vice President of the Buddy Program Claire Woodrow ’18 has worked with her team in Synapse to pair Stanford students with individuals suffering from a brain injury.

According to Chen, this structured buddy program creates an additional layer of social support and fosters long-term friendships. He added that, as many members of the student group are interested in neuroscience or hope to pursue a career in medicine, the partnership can give them valuable insight on the patient perspective of coping with a serious injury.

Totman — who founded Stanford Synapse with Konopka and Chen — created Synapse National in 2016. This umbrella organization seeks to expand the social support available to individuals with brain injuries and empower students to positively impact their lives with training sessions and written guides.

Synapse has since multiplied to include chapters at seven universities across the U.S. including ones at MIT, the University of Pennsylvania and Oregon State University.

Raising awareness

As director of outreach, Marcone contacts physicians in the mid-Peninsula area to help publicize Synapse to patients with brain injuries. She said that partnerships with physicians have been worthwhile in supporting Synapse’s work.

“While we’re not providing a medical service, [we’re] a unique and helpful service in recovery,” Marcone said. “That’s often something that doctors are really interested in getting for their patients, which they personally cannot provide.”

Chen added that partnering with local physicians to spread information about Synapse has contributed to the growth in its patient population.

“[Without that partnership], how would [patients] know about us?” Chen asked. “Brain injury patients tend not to use social media or their phones because the blue light can trigger a headache, so plain old paper and word of mouth is the best way to reach out to our local community.”

In this way, Chen added, Synapse is helping to fill a vacuum and be the main brain injury support group in the area.

“There’s definitely an unmet need here,” he said. “Part of the reason we started is that there really is no peer support group in the mid-Peninsula between [San Francisco] and San Jose.”

When it comes to raising awareness about brain injuries on campus, Marcone begins by clarifying to students what the term means.

“The most important thing is talking about the spectrum of brain injury,” Marcone said. “We sometimes use the word concussion in medicine because it sounds less scary than a brain injury,” but she said avoiding the term can be dangerous because it leads people to dismiss the seriousness of a concussion.

“I think there are a lot of people on Stanford’s campus who have had a brain injury,” Marcone said, though she conceded that only a small portion are actively involved in Synapse or attend the peer support group meetings. Marcone said she would like the group to reach out to student athletes more in the future.

Looking forward to next year, Marcone said that Synapse hopes to create a student-centered peer support group that helps students balance academics and their social life while living with a brain injury.

Bike safety

While Stanford is registered as a bicycle friendly campus, there were 626 crashes between 1996 and 2016, some with catastrophic consequences, according to Stanford News.

According to Stanford bicycle program coordinator Ariadne Scott, Stanford trauma surgeons note that 98 percent of people who suffer head injuries from bike crashes were not wearing a helmet.

Since bike accidents are a leading cause of brain injuries, Synapse has — alongside Stanford Parking & Transportation Services — been a vocal champion of safer biking practices.

For instance, in February 2018, Synapse hosted its first ever brain injury awareness symposium, “I Love My Brain,” for students and members of the public. The event revolved around the dual themes of bike safety and neuroscience research, and was co-sponsored by Parking & Transportation Services.

University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne, one of the speakers at the symposium, used the opportunity to address groundbreaking discoveries in neuroscience that could minimize brain damage and even accelerate recovery after the fact.

Survivors of brain injury, including Bullington and Stanford student Kevin Supakkul (who had a bike accident during his freshman year in 2015), were also panelists at the conference.

Russell Siegelman MBA ’73, a lecturer at the Graduate School of Business, also spoke at the symposium. In 2016, Siegelman and his wife, Beth Siegelman, donated 1,800 helmets to the freshman class of 2020 in an attempt to normalize helmet usage.

At the conference, Siegelman expressed his disappointment that few students ultimately wore the helmets.

Marcone raised a concern that the initiative might have had the unintended consequence of disincentivizing helmet usage.

“Having a helmet became a freshman thing,” she said. “Students can feel invincible, so it’s hard to tell them that [brain injury] could happen to you.”

Bullington, who kept a blog during his recovery process and continues to keep people updated about his daily progress on Facebook, said he is a strong believer in keeping people informed. In his experience, support can turn up in unexpected places.

“Oftentimes people think it’s better not to share because they don’t want to burden others, but you never know when help is going to come,” Bullington said.

Contact Yasmin Samrai at ysamrai ‘at’ stanford.edu