This article is the first in a mini-series examining the role, goals and challenges of community centers and other community-centered organizations on campus.

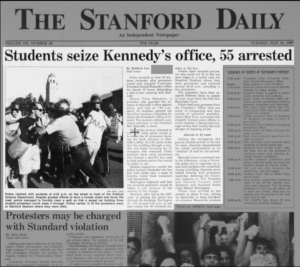

Community centers, part of Stanford’s campus since the late 20th century, are the work of continuous student activism and protest.

The centers’ push for increased resources — a perennial issue raised by student groups and representatives — has a long history. Challenges over the years range from a lack of professional staff and space for student groups to the threat of budget cuts affecting hours of operation and programming. This has led to a cycle of activism among students who hope to maintain and grow the community centers.

Early years

After a gradual admission of more and more minority groups to Stanford, students began to form their own community organizations: the Black Student Union (BSU) in 1967, the Asian American Students’ Association (AASA) and the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (MEChA) in 1969, the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) in 1970, the Gay People’s Union in 1971 and the Women’s Collective in 1972. As The Daily reported in 2012, community centers were created “as a response to the growing needs of a more diverse student population.”

Student activism was also a driving force in the centers’ establishment. The Black Community Services Center, the first community center to be created, formed in 1969 following BSU’s release of 10 demands that the University work harder to fight racial injustice; Black Student Union members outlined the demands after taking the microphone from then Provost Richard Lyman at a colloquium on white racism following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. The University quickly acquiesced to all but one of the 10 points.

The other community centers followed shortly over the next decade. But they all faced hardships. During their formation in the late 1960s and early 1970s, centers were solely staffed by students and did not receive any University funding.

This led to student outcry not only for more resources from the University but also for increased recognition of and dedication to supporting minority students on campus.

In the late 1980s, a coalition of minority student groups and students on campus put forth the Rainbow Agenda, a set of demands for institutional change at Stanford ranging from increasing minority enrollment to actively hiring more minority faculty members. The Students of Color Coalition organized protests in 1988 to demand a more multicultural education at Stanford. These student-led crusades helped push successfully for University resources and funding to grow community centers almost two decades after the first center’s establishment.

The Asian American Activities Center received its first full-time director, Rick Yuen, in 1989; other centers also began to gain professional staff. However it was not until 1994 — following student activism on the issue — that the University gave funding for center programming. That year, four student protesters began a hunger strike, demanding the creation of a Chicano/a Studies major as well as the construction of a Stanford Chicano/a community center in East Palo Alto.

Funding challenges continue

Community centers’ resource issues did not end when they got funding from the University.

According to a 1990 Daily article, the centers almost entirely escaped budget cuts that affected many groups across campus, because of what Michael Jackson — associate dean of Student Affairs at the time — called the centers’ “integral role in the University’s academic mission.” However, there was little room for the centers to grow at a critical point in their emergence.

“The … community centers [that did not see cuts] are young, underdeveloped and underfunded, so any cut would effectively cripple them,” one University staffer said.

In 1994, community centers were asked to consider how their spaces would look and operate under five, 15, or even 30 percent budget cuts when submitting their budget proposals to the University administration. While the lower percentage cuts would lead to consequences such as eliminating travel budgets or decreasing hours for support staff, larger cuts would lead to more drastic outcomes. Directors would be asked to cut their work time in half, most student staffers would not be paid and centers would shut down during the week, only operating on weekends.

The budget proposal was created by leaders of El Centro Chicano, the Black Community Services Center, the Asian American Activities Center and the American Indian Program. Titled “Opportunity and Challenge: Foundations for the Future of the Ethnic Community Centers,” it read, “Each of the centers runs on a skeletal budget. Cuts of any level would likely result in a reduction of staff.” The proposal went on to outline the difficulties centers already faced in affording supplies, postage, repairs and maintenance.

Community centers’ budgets had been at a standstill since 1990, and the prospect of budget cuts forced centers to consider eliminating advising, community publications and minority student and faculty recruiting. In these budget plans, however, community centers made sure to emphasize their “contribution to the academic mission of the University” — their work “[supporting] schools and departments in their efforts to identify, recruit and retain minority faculty” and “[facilitating and assisting] undergraduate and graduate student development, recruitment and retention.”

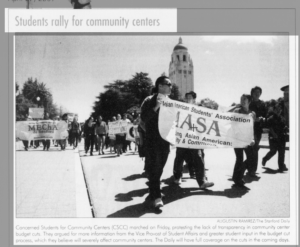

Stanford Concerned Students for Community Centers took out an ad in The Daily in November of 2000 calling for the creation of a permanent base budget for centers, a guarantee of sufficient and central space, permanent funding for at least two full-time employees per center and community centers’ ability to fundraise for themselves.

By May 2001, each of the centers had been granted $50,000 in programming funds for the next year, half of which resided in their base budgets. The other half took the form of three-year discretionary funding; the intent was to make this chunk of the funding permanent in the future. The Women’s Community Center and the Queer Student Resources Center (then called the LGBTCC) also received full-time assistant directors.

However, following the financial crisis in 2007, Stanford introduced a $3 million budget cut to the University’s Student Affairs division. The six community centers experienced payroll reductions in the form of reduced work hours for professional staff and decreases in their operations and programming budgets.

The cuts came at a particularly difficult time for the Native American Community Center (NACC), forcing them to limit center staff to 2.5 employees despite a record-high admittance of 95 Native American students to the class of 2013. Each center was also required to reassess annual special events and programs, such as the NACC’s Powwow, the BCSC’s Academic and Community Awards program and El Centro’s Professional Development Symposium, El Dia de los Muertos and Cesar Chavez Commemoration. The lack of funding also meant that student staff members had to be laid off, with most community centers eliminating a few student staff positions and anticipating fewer student staff hires for the upcoming school year.

With the intent of evaluating each office under its supervision, Student Affairs conducted a review of community centers in 2012 consisting of three parts, according to a Daily article: “a self-evaluation completed by each center, a review done by an internal steering committee and finally a review done by an external committee of people in collaboration with the community centers.”

Greg Boardman, then-vice provost of Student Affairs, told The Daily at the time that he did not anticipate further budget cuts after the 2009 reductions.

“If anything, there’s a possibility of increased funding if we identify additional needs that are not being met,” he said.

Since the 2009 cuts, the University has created the Office of Diversity and First-Generation Programs, now DGen, and the Leland Scholars program to take responsibility for some of the work previously done by the community centers.

Issues with space

When they were first established, community center offerings were not as accessible as many wished: Student groups that wanted to use El Centro phones, for example, were required to pay part of the cost. Resources were strained: 35 student organizations squeezed to meet regularly at the Asian American Activities center, which meant that meetings were often overbooked. And on top of these issues, there were not enough staff to tend to the growing population of center users. Full-time directors worked 10 to 12 hours a day, and sometimes even on the weekend to make up for the lack of manpower.

The 2001 Concerned Students for Community Centers ad also addressed the issue of space, another problem that community centers struggled with as they grew in size. The ad argued that centers using Old Union would need to find alternate accommodations in light of the building’s possible renovation and that the Black Community Services Center deserved a larger and more adequate space.

As the Black Community Services Center (BCSC) began looking for a space to accommodate its needs, other centers such as El Centro Chicano and the Queer Student Resources began to express similar worries. Center leaders pointed out a lack of not only meeting spaces but also performance spaces and storage spaces for student groups.

Groups hoping to utilize the centers fought for space: Lisa Moore, former assistant director of the Women’s Community Center, stated that the WCC’s “calendar [was] usually booked within the first weeks of school, for months, and it means that other student groups who don’t get organized right at the beginning might not have the space to meet in.”

Present-day issues

Centers continue to seek expanded resources and presence on campus.

In 2013, a seventh community center, The Markaz, was formally established by Stanford to serve as a resource center for engagement with Muslim cultures and peoples.

“It felt really nice to have a support system of people who could understood me on a different level than other people who I was meeting here could,” Majd Quran ’19 said in an interview with The Daily in 2016.

While the number of community centers has grown, administrative shifts have complicated centers’ advocacy for funding. Nicole Taylor ’90 M.A. ’91 served as the associate vice provost for community engagement and diversity from the fall of 2015 to early 2017. In an interview with the Daily in 2016, she described her role as that of “the translator between administration and students, translating how each side feels about an issue and how we can come together.”

After Taylor’s unexpected departure in 2017, community centers were placed into an interim structure. The seven community centers fell under the supervision of the Vice Provost of Student Affairs (VSPA), while the Diversity and First-Generation Office (DGen), the Haas Center for Public Service and Student Activities and Leadership (SAL) were asked to report to separate associate vice provosts.

The 10 groups had previously been placed into one collective VPSA unit called Community Engagement and Diversity, an initiative to “[empower] students to lead in a multi-racial, multi-ethnic and pluralistic society.” The reorganization was also an effort by leaders in VPSA and in the Community Engagement and Diversity centers to seek increased funding for the groups from the University Budget Group. However, the Budget Group gave the centers a more modest investment than they had hoped, forcing centers to again reconsider their ability for staff growth.

In a series of recent op-eds in The Daily, community center student leaders outlined the importance and impact of their organizations to the Stanford community and sought increased support from the administration, especially in terms of funding. The editorials are reminiscent of student activism.

“Stanford has neglected its community centers for far too long,” wrote student leaders from El Centro. “We are not just models on brochures. We are real people who expect excellence and equity from a Stanford education.”

The op-eds also addressed center-specific needs. Queer Student Resources sought budgetary increases to support more undergraduate staff, the creation of a graduate student staff and a fund to bring relevant speakers to campus. Other groups that wrote op-eds included the Asian American Activities Center, The Diversity and First-Gen Office, the Native American Cultural Center, The Markaz and the Women’s Community Center.

“The community centers on campus are crucial places for so many students at Stanford,”Rawley Clark ’20 wrote for the Women’s Community Center op-ed. “They provide us with places to learn, to grow, to create. They are spaces where we can speak our truths and know that we will be heard. They are spaces where we can question and challenge thoughts and push ourselves outside of the boundaries of our knowledge.”

Students have long felt that community centers provide a welcoming space, one that allows them to feel closer to their identities.

Upon first entering the Native American Cultural Center (NACC), “I had found my community, and my home and a place where I just wanted to be,” said ASSU community center lead Carson Smith ’19.

Students also emphasize, though, that community centers are more than a place of respite. Lina Khoeur ’18 explained how the centers have informed and motivated her activism.

“Community centers are a space where you can get checked by other people who are doing this work,” Khoeur said. “It’s where I got politicized and where I can ask questions like, ‘What does it mean to have this identity?’ and to be in solidarity or think about issues like blackness in the Asian American community.”

Khoeur also expressed her belief that community centers have a broader role at Stanford than many people think.

“I think the perception is that community centers are spaces where people go run and hide and don’t have to, like, push the boundaries and don’t have to address tensions and conflicts,” Khoeur said. “My experience has been the exact opposite.”

Contact Felicia Hou at fhou ‘at’ stanford.edu.