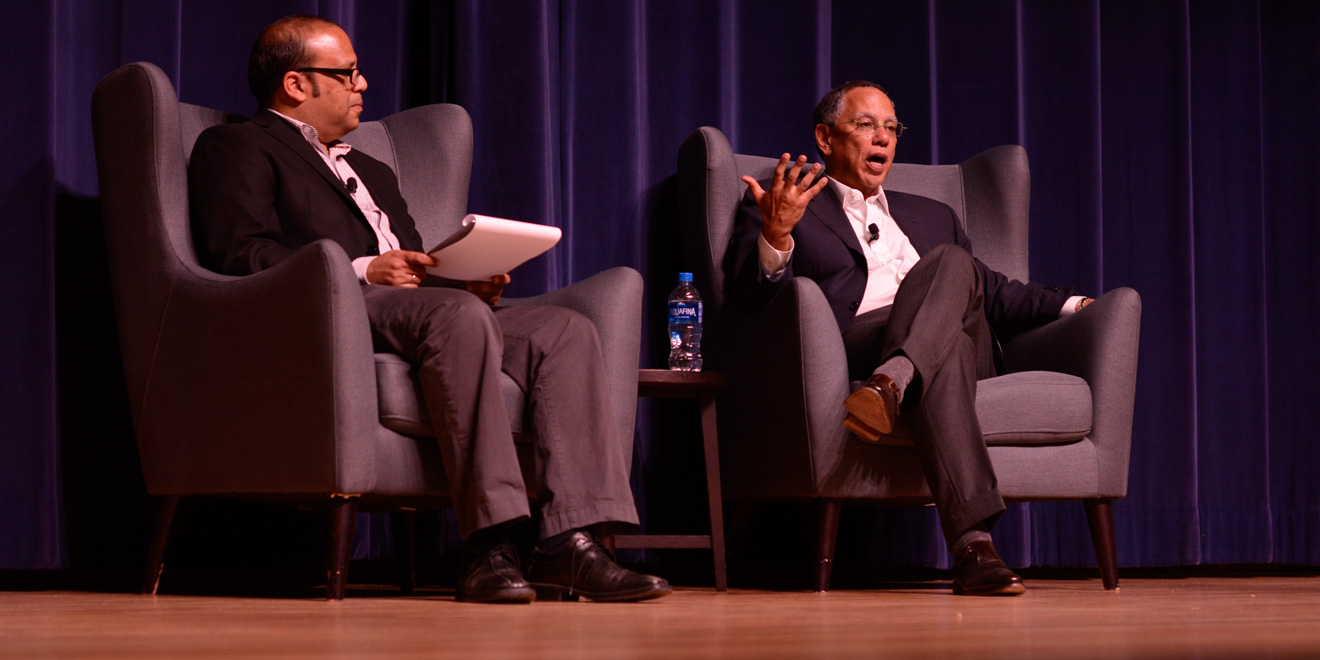

Executive Editor of the New York Times Dean Baquet has held the newsroom’s highest ranking position since 2014, where he has overseen coverage of content ranging from President Donald Trump’s Russia controversy to reporting on Harvey Weinstein and the #MeToo movement. On Tuesday night, Baquet addressed audience members in Cubberley Auditorium as part of an event hosted by the Brown Institute for Media Innovation. Prior to the event, he also sat down to speak to The Daily about Stanford’s open-mindedness to differing viewpoints, the New York Times’ coverage of Trump and how technology is changing the journalism field.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): What do you think is the most important issue that we should be reporting on here at Stanford or more broadly in Silicon Valley?

DB: I don’t think there is a university that has had as much impact on the culture of America in the last 25 to 30 years. I mean you wouldn’t have Silicon Valley without Stanford. I think that’s a great story. I think the effect one has on the other is a great story. [On a tour today] I saw the Hoover [Institution], which is probably the most credible conservative think tank, and if it was on a campus at Berkeley it would’ve been burned down. If it was on the campus of Columbia there would be constant protests, and it’s just interesting to me.

I don’t mean that to criticize Hoover. I just meant it’s an interesting cultural phenomenon because universities have a personality. I actually think it’s a compliment, from where I sit, that you could have a conservative think tank on a university campus. There are a lot of universities that wouldn’t — the equivalent of the universities that wouldn’t have had ROTC [Reserve Officers’ Training Corps] while I was in college.

TSD: Stanford has invited a series of leading figures, some of which have been controversial, to come speak on campus through Cardinal Conversations, and I’m interested in hearing more of what you have to say about universities inviting these speakers, and relatedly how the New York Times covers some of these small and vocal fringe groups?

DB: I do think there’s a trend in universities now to not want to hear from a variety of voices, which makes me a little bit anxious. Again, I’m not talking about obviously racist or anti-semitic [rhetoric], but it’s not unlike what’s going on in newspapers. When the editor of the editorial page picked Bret Stephens as a columnist, people were really upset. I thought there were going to be protests. And I disagreed with that. You should want to hear from other thoughtful voices even if you disagree with them, because at the heart of journalism is inquiry and understanding. And I would say the same for universities.

Don’t forget, most journalists, including me, did not think Donald Trump would win. And that means there’s a whole chunk of the country that we don’t understand. If you only listen to people who you agree with – what’s the point of that? Stay home.

TSD: The New York Times’ reporting on Harvey Weinstein launched the #MeToo movement and a wave of reporting on sexual harassment and assault. Can you talk a bit about the particular journalistic or ethical challenges of those stories and how you/other people at The Times navigate them?

DB: They were difficult, to start off, in that all of the people we wrote about were powerful men. I mean Harvey Weinstein in his world was very powerful. And Bill O’Reilly in his world was very powerful. And people didn’t want to talk about them because they could hurt their careers. The device that made it work was that we started to understand how many of these cases had lead to settlements. And if there was a settlement that gave you a concrete way to capture the fact that something had really happened. In some cases, like with O’Reilly and Weinstein, the men themselves were just bullies. They tried to bully us — the good thing about working for a big powerful institution, is that it’s hard to bully the New York Times.

TSD: How is covering the Trump administration different than past administrations?

DB: [Trump] tells lies. All politicians tell lies, but he does it more publicly than any politician I’ve ever seen, and I covered Southern politicians. He also doesn’t have a bedrock set of principles. I was Washington Bureau Chief during the [George W.] Bush and Obama administrations. You sort of knew what Bush and Dick Cheney stood for, and you knew what Barack Obama stood for. Constant attacks on the press, which are meant to undermine all of the institutions that are independent, such as the press, the judiciary, the justice department – all of the institutions that are not beholden to him – he attempts to undermine regularly.

TSD: How do you think artificial intelligence will affect journalism?

DB: I think it will have a huge impact. Personalization, that bothers some people. That doesn’t bother me. We will always give you the big stories, and the things we honorably think you should read. But nothing is more personalized than the print newspaper. My wife, son and I would get the print paper in the morning, and I read some stuff first, they read some stuff first, but it’s always been personalized. AI will make it easier, and I think the possibilities are tremendous. I’m sure there will be bad stuff. But all of this stuff ends up being better for journalism. Don’t be in league with the people who look at every change as something really awful.

TSD: What keeps you up at night?

DB: A lot of things. I have reporters who are covering war. I’ve had reporters who have worked for me who have been killed or almost killed. At the height of America’s various wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and other places, I’ve had to participate in the decision about whether or not [a reporter] could go someplace. Good war reporters always want to go where the action is. But war today is very different than it once was. If you read the accounts of Vietnam and elsewhere, both sides sort of understood that reporters were neutral. That’s not the case anymore. I mean the people who the US is engaged in wars with are very angry with the US, and do not see reporters as neutral. One of the reporters who I was closest to on the NY Times staff – I had also worked with her at the LA Times – was almost killed in a helicopter crash a few years ago. When I first saw the pictures of her I was certain she wasn’t going to make it. I was the one who had to call her mother and her sister and her husband to tell them what happened. And that’s what keeps me up at night.

This transcript has been lightly edited and condensed.

Contact Ellie Bowen at ebowen ‘at’ stanford.edu.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the name of NY Times columnist Bret Stephens. The Daily regrets this error.