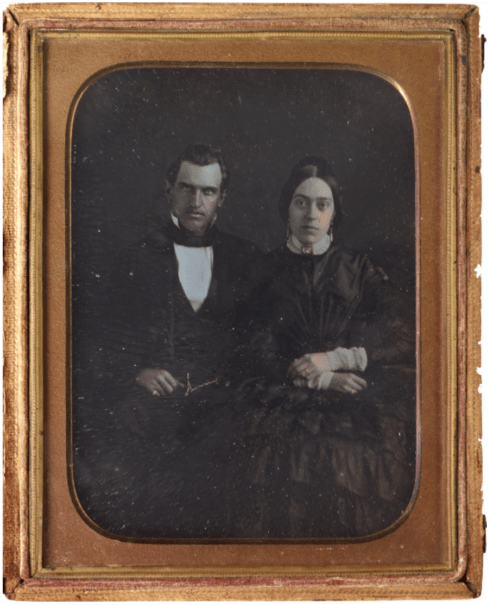

Working in the Cantor’s Art + Science Learning Lab, I find strange objects almost every day. Most recently, I found a daguerreotype of Mr. and Mrs. Stanford taken in 1850 to commemorate their marriage in that same year. The word daguerreotype conjures up images of anonymous soldiers from the Civil War, which broke just out ten years later. The early photographic process promised accurate treatments of the face but could not help but produce ghostly images of black-clad sitters with sunken eyes. Stranger still, the portrait of the young Stanfords reminded me of how William Faulkner describes photography, death and commemoration in his short story, “All the Dead Pilots.”

Mr. and Mrs. Stanford wanted to cheat death through this image but they achieved the opposite. Jane’s cheeks, earrings and necklace have all been painted after the fact to appear more lifelike, as have her hands and wedding ring; Leland Stanford, Sr. presents his signature pinky-ring and gilded-age pocket watch. The two are younger than they appear in any painted portraits, but for all their youth and added fleshy tones, the Stanfords are somehow dead in this image.

In his “Camera Lucida,” Roland Barthes calls photographers “agents of death.” Barthes writes that a portrait like that of the Stanfords “produces Death while trying to preserve life.” Jane’s dress retains its folds of fabric but becomes hazy and flat at the bottom of the portrait, as though the image were a dream. Leland’s necktie is similarly palpable but his limbs fade into the picture. The Stanfords did not enter into immortality through the daguerreotype but ceased being just as the camera flashed before their eyes. They “are not,” but they “will have been.”

The daguerreotype is even harder to grasp in person. The image reflects light like a mirror. The newly married couple appear beneath a pane of glass bonded to a polished silver plate. They refuse to be seen under anything but dim, mournful light.

In this strange portrait, Mr. and Mrs. Stanford anticipate Faulkner’s “All the Dead Pilots.” Faulkner opens his short story with descriptions of photographs, “the snapshots hurriedly made, a little faded, a little dog-eared with the thirteen years” since the end of World War One. Next, he describes the men in the photographs, pilots of the Royal Flying Corps, as “lean, hard, in their brass-and-leather martial harness, posed standing beside or leaning upon the esoteric shapes of wire and wood and canvas in which they flew without parachutes.” Faulkner fixates upon the word esoteric, drawing a parallel between the men and their craft. “They too have an esoteric look,” he writes of the pilots, “a look not exactly human, like that of some dim and threatful apotheosis of the race seen for an instant in the glare of a thunderclap and then forever gone.” For Faulkner, the pilots are not made present through the exactitude of modern technology. On the contrary, they become “esoteric” through the lightning-strike of the camera. Like the Stanfords, Faulkner’s pilots fall out of time through the act of commemoration.

Faulkner imagines the pilots in middle age. “In this saxophone age of flying,” he writes, “they look as out of place as, a little thick about the waist, in the sober business suits of thirty and thirty-five and perhaps more than that, they would look among the saxophones and miniature brass bowlers of a night club orchestra.” The pilots died the day they were photographed, writes Faulkner. “The young men who once swaggered” ceased to exist when they swapped their brass-and-leather martial harnesses for sober business suits. They died “in the glare of a thunderclap,” which supposedly guaranteed their immortality. They “will have been.”

Eduardo Cadava further explains these connections between war, photography and death. “There can be no image that is not about destruction and survival,” he writes. “What dies, is lost, and mourned within the image – even as it survives, lives on, and struggles to exist – is the image itself.” The faded photographs with which Faulkner begins his story are the true subjects of his work. Faulkner concludes: “And so, being momentary, it can be preserved and prolonged only on paper: a picture, a few written words that any match, a minute and harmless flame that any child can engender can obliterate in an instant. A one-inch sliver of sulfur-tipped wood is longer than memory or grief; a flame no larger than a sixpence is fiercer than courage or despair.” Faulkner may as well have been thinking of Mr. and Mrs. Stanford, whose morbid likenesses were captured on chemically treated wood by means of a flame no larger than a sixpence. His pictures, like their daguerreotype, suspend the subjects of photography in death not life.

Contact Reilly Clark at reilly2 ‘at’ stanford.edu.