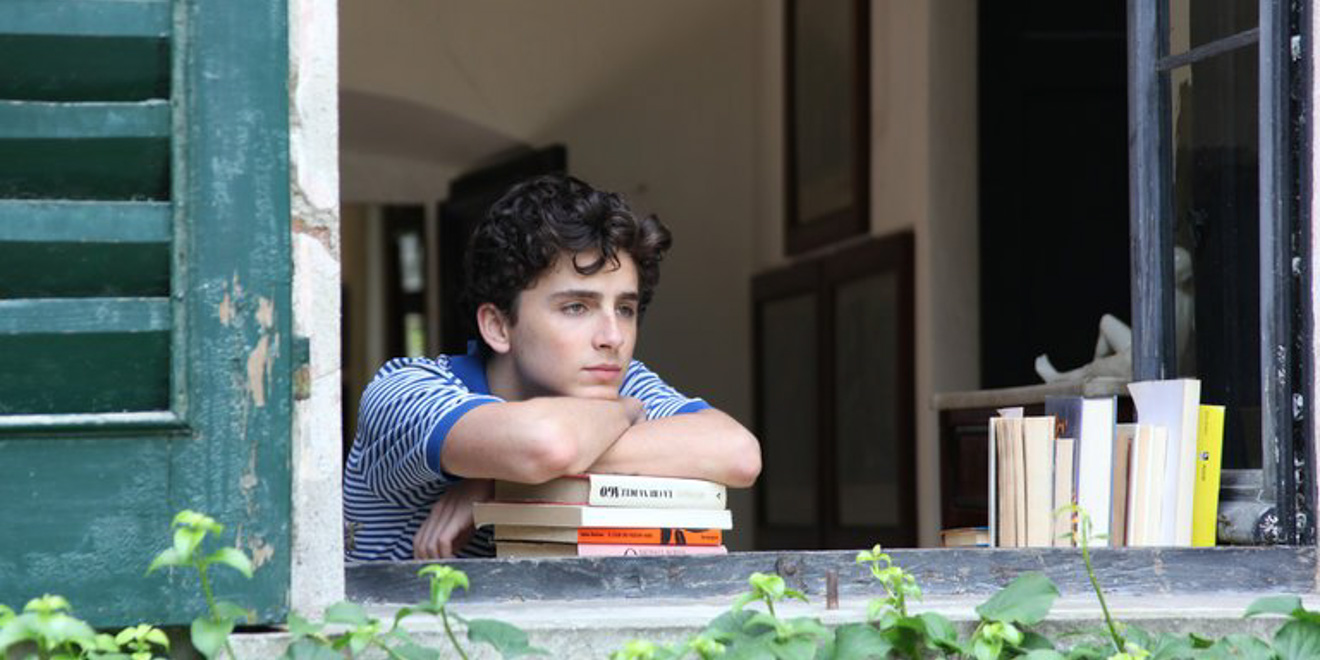

“Call Me By Your Name,” from the rippling contours of ancient statues’ triceps to the hazy pastels of Elio’s favorite boardshorts, is an aesthetic experience. And that’s exactly what critic D.A. Miller of the LA Review of Books dislikes. The film’s emphasis on “The Beautiful Life,” he argues, glosses over the gritty details of a quintessentially homosexual, coming-of-age tale; the pretty stuff points away from the gay, makes the film palatable to a straight audience.

Miller’s issue with “The Beautiful Life” is entangled with the movie’s emphasis on “The Good Life.” He chides the mother’s effortless translation of a German story, whose themes so readily relate to her son’s relationship, the way Elio speaks multiple languages “for no apparent reason but to demonstrate that he is as proficient in them as he is at the piano, an instrument he plays like a virtuoso without needing to practice.” On the trip to the father’s archeological site, Miller persists: “No arduous dig for this archeologist; his latest find has simply floated up from the bottom of the nearby lake.” Miller adds these to a list of believability woes, shared by New Yorker critic Richard Brody who says that “[Director] Guadagnino can’t be bothered to imagine … what [Oliver and Elio] might actually talk about while sitting together alone.”

There is admittedly a shimmering, glazed-over quality to the movie that extends from the palette to the people: the way Elio’s parents flow into the narrative without hindering the central conflict, the languid afternoons where nothing moves, the beautified milieu in which they (sometimes literally) swim all fit into a sense of narrative flatness. With the notable exception of the father’s last monologue, we never see relationship-building conversations but rather gestures towards them. However, it is from this placid facade that the heart of the experience, Elio’s desperate, undivided focus on Oliver, surfaces. All else slips easily around the central, emotional vantage: a mind in love.

This beautified gloss is characteristic of a mind in love but also a mind remembering (in this case, it is both). The original novel on which the film is based, we forget, involves a frame story in which an older Elio looks back at his adolescence. Guadagnino’s choice to set the movie in the present gives it a heightened sense of immediacy, but tendrils of the book’s retrospective framework linger in the film’s nostalgic sheen. We get the sense, for instance, that stumblings of the mother’s translations, the difficulties of the archaeological dig, elements of realism that Miller and Brody seem to desire are all caught in memory’s filter. Inasmuch, Miller’s “Beauty Treatment” casts “Call Me By Your Name” in the hazy glow of reminiscence.

While Brody thinks the lack of particulars feels “disingenuous,” Miller is more concerned with the implications for representations of male homosexuality. He cites the cinematography at the crux of sexual intimacy between Elio and Oliver, as “the camera modestly pans away to contemplate, not for the first time, the lovely orchard outside … The beauty of this beauty is that it gets us outdoors to a scene that, because no more than scenery, is not homosexual.” But the camera’s averted gaze serves a thematic purpose that requires just this kind of beauty, for Elio’s summer lingers in the space between “looking at” versus “looking away.” In their first moment of contact, Oliver puts his hand on the boy’s shoulder as the two watch the volleyball game. Whether it is the archaeological ruin, or the museum statues, or the egg or apricot or peach, their dynamic is always triangulated between their bodies and the objects they view; they look at each other by looking at something else. The subject of the film is not the sex itself but the suggestion of it, and so a camera pan at the moment of consummation seems only fitting.

Miller sees this reading as evasively universal and most egregiously represented by Mr. Perlman’s final conversation with Elio, in which he expresses the most explicit acceptance of his son’s experience, even hinting at his own homoerotic inclinations (a scene, funnily enough, lauded by Brody as “moving and wise,” “a rich and potent Oscar syrup”). Miller, on the other hand, finds the scene “repulsive in the root sense: it seeks to drive away every possible understanding that might make the relation with Oliver a serious sexual experience for Elio — and thus also make it that significant social experience we call “coming of age.”” He continues: “the professor’s appreciation of friendship … is far more homophobic than any simple elision of gay sex.” Gay sex, not gay sensuality, which skips over “what would be unkind to show or off-putting to see here: the unlovely spectacle of blood, shit and pain that is the initiation of Elio’s desiring asshole.” In other words, Guadagnino does not confront the reality of male homosexual coming-of-age.

Is there a deficit of gay representation sans the gentle brush of CGI’s crotch-flattening click? Certainly. But if the gloss is not gratuitous, rather evocative of memory itself with its own elisions and sensuous insinuations, then these explicit displays (blood, shit, pain) do not fit in. Here we reach an interesting juncture and a question that Miller does not directly address: What happens when there is a discord between aesthetic cohesiveness and political project? Do we need every homosexual representation to display the gritty particularities of the homosexual experience?

What’s funny is that part of Miller’s concern is not that different from the concern of our protagonist himself, with whom we are left at the end of the movie. In the final scene Elio sits, still adolescent, crying into the fire while Sufjan Steven’s “Visions of Gideon” plays in the background.

Our critic missed the ending on his first time round — he only caught it on his second viewing (the interim time, one imagines, was spent writing most of his review). In a way, his re-watching is fitting, for the boy’s own sense of return is most palpable in the last scene. Miller recalls, “[Elio] looks “into” the fire, at nothing but an inwardness that he can no longer imagine finding expression in the blur of the Beautiful Life behind him.” In a sense, Miller is right. But he misses the fact that the beauty of the whole movie is necessary to the feeling that something is past.

The convergence of beauty and memory, the palpable sense of innocence lost, recalls something of an anachronistic comparison — an 18th Century poem by William Wordsworth — in which the poet returns after five years estrangement to Tintern Abbey, where he first experienced a joyous connection with nature’s splendor. The poem’s nostalgic undertones (though lacking a certain gayness) overlap strangely with Guadagnino’s Italian scenery and feel almost like a forerunner to Elio’s weepy fireside scene:

“For nature then

(The coarser pleasures of my boyish days

And their glad animal movements all gone by)

To me was all in all. — I cannot paint

What then I was

The sounding cataract

Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock,

The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood,

Their colours and their forms, were then to me

An appetite; a feeling and a love

…

That time is past,

And all its aching joys are now no more,

And all its dizzy raptures.”

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that poem and movie share an emotional luster, for Wordsworth is concerned with the idea of returning, of what it means to lose something that once was. He points to his own disconnection from his past self: He “cannot paint what then [he] was” but only how it looks from here — precisely what Guadagnino aims to do, stripping the movie to its sensuous glow. We have seen Elio’s boyish days, unbracketed by the full distance of the book’s retrospective narration. And yet, we have not seen it unfiltered by memory’s selective (and aestheticizing) lens.

Sufjan’s lyrics, like Elio and for that matter Wordsworth, hovers on this precipice of experience and recollection:

“I have loved you for the last time

Is it a video? Is it a video?

I have touched you for the last time

Is it a video? Is it a video?”

In its chamber-like recurrence, we are thrust into the mind of our protagonist, who is beyond the story but not yet able to make sense of it. We feel his desperate groping for the reality that underlies Oliver’s last words to him: “I remember everything” and sense that part of the boy’s heartbreak is his inability to recall the experience in its entirety. From our vantage by the fire, we see (hear, feel) memory burgeoning. Memory as a video, a vision, a thing distinct from experience itself.

Wordsworth, Elio — and yes — Miller are all preoccupied with the same questions: What did I experience? How will it be remembered? For Wordsworth, it’s communion with nature, for Elio, his summer with Oliver, and for Miller, the experience of nascent homosexuality in an era that appears increasingly and, for him, deceptively tolerant.

Miller’s predicament might take more discussion, but “Call Me By Your Name,” in all of its languid beauty, its sensuous excess and narrative simplicity, gives us its answer.

Contact Emma Heath at ebheath ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Correction: D.A. Miller’s name was originally spelled as “D.A. Muller.” It has since been corrected.