Stanford has nearly 10 billion dollars invested through corporations in the Central America and the Caribbean, analysis of the University’s tax returns shows. Much of this money, which is held offshore in places like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, is not subject to full taxation.

Following the leak of the “Paradise Papers” in November, Stanford’s ties to several “blocker corporations” in the Caribbean that allow the University to skirt some or all taxation on investments were brought to the forefront. The University’s most recently available Form 990 — the IRS return for 501(c)(3) nonprofits — adds to this picture, revealing an investment strategy that overwhelmingly favors low- or no-tax overseas assets.

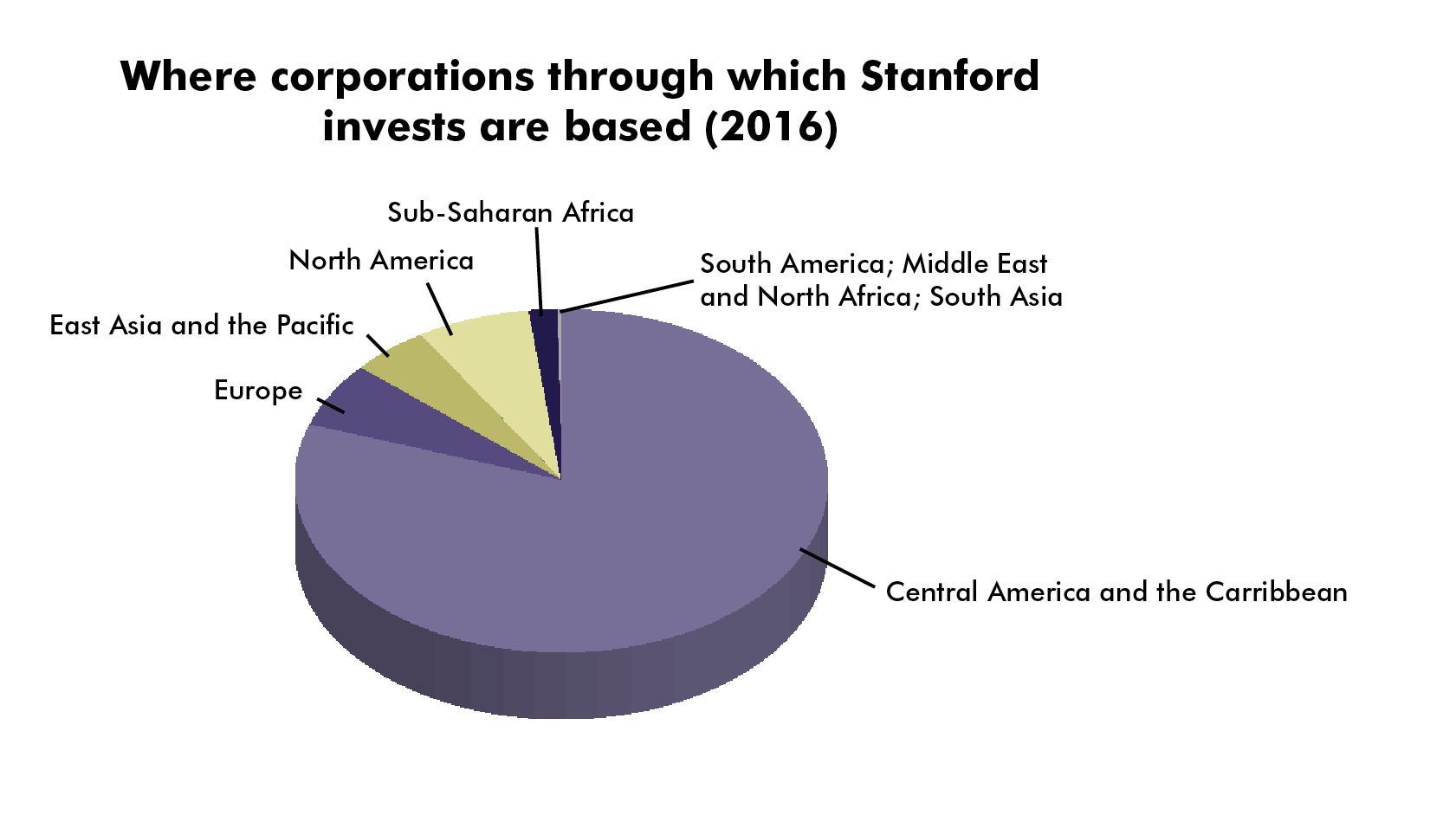

In 2015, Stanford’s Board of Trustees, which manages the University’s investments and other assets, reported $9,653,379,283 worth of investment through corporations based in the Central America and the Caribbean.

As of Aug. 31, 2017, the University assessed its total investments at $33.3 billion.

Stanford’s investment through Central American and Caribbean groups outpaces its investment through corporations in any other region outside the U.S., by an order of magnitude: The second highest amount of investment, made through groups in Europe, was less than one-tenth that, at only $708,684,707.

Form 990s from past years show a similar emphasis on Caribbean-based investment options.

This massive investment made through corporations in the Central America and the Caribbean is not reflected in other expenditures in the same region. For most other reported categories of activity, including “Study Abroad,” “Foreign Travel,” “Education” and “Conferences and Seminars,” the only region in which Stanford reported less investment was Russia and Neighboring States.

The Paradise Papers revealed that Stanford has partnerships with several Caribbean investment groups, including the Bermudan H&F Investors Block and the Cayman Islands-based Genstar Capital Partners V HV.

Stanford’s 2015 Form 990, meanwhile, names 15 partners, corporations and trusts based in the Caribbean, as well as in Mauritius and Jersey, a small island off the coast of France. Jersey, Bermuda and the Caymans all have a 0 percent corporate tax, while Mauritius’ is 3 percent.

Of these partner organizations, Stanford only owns a 100 percent stake in seven. However, it owns over 50 percent in all 15.

One partner corporation, the Cayman-based Stanford SGGS Europe, Inc., received media attention in 2008 after then-presidential candidate Barack Obama alluded to it in a speech.

“You’ve got a building in the Cayman Islands that supposedly houses 12,000 corporations,” Obama said of Ugland House, where the Stanford Hospital-affiliated SGGS Europe is based.

“That’s either the biggest building or the biggest tax scam on record,” he added.

Additionally, the University reported that Cephei Capital Management Company Ltd. (also located in the Caymans) was its fourth highest-paid contractor in 2015.

“It is common for universities, foundations and other nonprofit organizations to have a portion of their endowments invested in offshore funds,” University spokesperson EJ Miranda wrote in an email to The Daily. “When Stanford invests through offshore entities, it does so to meet its fiduciary obligations. Like many other institutions and families, Stanford looks to minimize its tax burden within the limits set by law. Indeed, [the California Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act] explicitly advises trustees to consider ‘the expected tax consequences of investment decisions or strategies.’”

However, he declined to go into further detail about H&F Investors Block, Genstar Capital Partners V HV or any other particular affiliates.

“We do not discuss specific investment strategies,” Miranda said. “Financial information is available to the public through our annual reports.”

Universities generally enjoy 501(c)(3) status and thus tax exemption, but when they engage in certain for-profit activities — including investment practices — that status can change.

Thus, blocker corporations, like those revealed in the Paradise Papers, are used to create “another corporate layer between private equity funds and [university] endowments [that] effectively blocks any taxable income from flowing to the endowments,” The New York Times explains.

And by establishing the corporations in places without corporate taxes, like the various Caribbean islands where Stanford SGGS Europe, Inc. and its peers operate, that taxation is minimal.

“Stanford complies with all applicable tax and other laws and, to the extent it invests in offshore entities, such transactions are in accordance with U.S. tax laws,” Miranda wrote. “Stanford provides IRS-required information about its offshore investments in its annual tax filings.”

Indeed, this investment strategy is explicitly referenced in the federal tax code.

“You intend to form a corporation in Foreign Country (Corporation) for the purpose of facilitating and managing your foreign investing, which will include distressed-debt investing,” the IRS says in a filing document aimed at 501(c)(3) organizations like Stanford. “Working closely with your investment advisors, your managers determined that your foreign investments can be better managed, result in a more tax-efficient structure, and enhance your ability to fulfill your charitable mission by using the Corporation.”

As the Paradise Papers highlight, this is a widespread practice among elite universities. Columbia, Yale, Penn, Princeton, the University of Chicago, Colgate, Dartmouth, Duke and many others are named throughout the documents.

According to a 2015 analysis by the Congressional Research Service, 11 percent of higher-education institutions possess 74 percent of the total wealth.

For Stanford, a self-described “$5.9 billion enterprise,” its endowment and investment portfolio are fundamental to its ability to fulfill the socially beneficial role that earned it 501(c)(3) status in the first place.

“Stanford University is a charitable institution,” Miranda wrote in his email. “The investment gains arising from the University’s endowment are a critical factor in supporting instruction, research, patient care and financial assistance for students who otherwise could not afford to attend.”

The question of Stanford’s tax-free assets has become especially pertinent after President Donald Trump and a Republican Congress passed a new tax bill in December. One of the bill’s more controversial provisions is a 1.4 percent tax on investment income by universities with endowments above a certain cut-off.

In a December blog post, University President Marc Tessier-Lavigne and Provost Persis Drell criticized the tax and the threat it posed to Stanford’s endowment.

“The endowment at Stanford provides essential support for our core academic mission, including research, education and student financial aid,” the two wrote. “Those things, in turn, provide immeasurable benefits to the economy, health and culture of our country. Though the advocacy efforts of the higher education community reduced the number of institutions to which this new endowment tax applies, these efforts unfortunately did not succeed in preventing its adoption entirely.”

Even under the new taxation plan, Stanford’s money in Central America and the Caribbean may not be impacted.

“The new tax would affect about 70 elite private colleges,” The New York Times noted, “though it would not touch [certain types of] offshore benefits.”

Miranda, though, said Stanford anticipates paying the new 1.4 percent tax regardless of where investments are made through.

“As far as can currently be ascertained, while we wait full direction from the IRS, the new 1.4% tax on endowment investment income will apply equally to income arising in offshore and onshore vehicles,” Miranda wrote in an email to The Daily.

Contact Brian Contreras at brianc42 ‘at’ stanford.edu.

This article has been updated to clarify that it discusses investment made through corporations based in Central America and the Caribbean and that the aforementioned investments are not necessarily allocated in that region. The Daily has also added comment from Miranda about taxation of endowment investment income under the new tax plan. Finally, an earlier version of the article stated that much money invested through corporations based in places like Bermuda and the Cayman Islands is not subject to taxation; in fact, the money is not subject to as much taxation as it would be if not held offshore. The Daily regrets this error.