Everyone is familiar with the struggle and unease of confronting someone face-to-face. The Cantor Arts Center’s exhibition “About Face” places viewers in this intimate and tense engagement with American portraiture of Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Gutmann, Barbara Morgan and Edward Weston from the 1920s to 1940s. Both subject and viewer stand uncomfortably close to the frame of the camera, provoking a moment of examination and introspection one usually seeks to avoid.

When standing a few yards from the entrance, the space appears deceptively spacious, yet upon entering, one realizes that the room is probably no more than 10 feet by 12 feet in size. Considering the nature of the exhibition, however, it becomes clear that this minuscule area is the most appropriate way to display the works.

A blurb printed in crisp white on a dark gray wall explains the stark immediacy of the exhibition. In a rapidly changing America – still recovering from the Great Depression (1929-39) and World War II (1939-45) – these five featured photographers transform their art’s aesthetic. Deviating from soft-focus, idealized images of the previous era, their portraiture confronts viewers with the same vivid detail that Americans had been confronting for the past decade of violence and poverty. Through manipulating shadows and fabrics and the very details of their subjects’ faces, Adams, Cunningham, Gutmann, Morgan and Weston push their abstracted images past mere image-recording and firmly into the realm of fine art.

Once inside the room, the viewer is presented with 13 portraits, most of which are miniature in size. When viewed from the entrance, they appear to be little more than black and gray rectangles framed by white rectangles. One begins to slowly realize that the size of the room suggests that it is best experienced one person at a time – it feels stiflingly crowded when two people are inside.

The play between intimacy and intrusion becomes more apparent the closer one gets to the walls. By design, the small size of the photographs necessitates that the viewer walks up close and leans towards the frames to be able to see and appreciate the content. This is contrary to the fear of being too close that exists in every well-meaning museum-goer. The closer one gets to the photograph, the closer one also gets to being yelled at museum security.

An uncomfortable sense of voyeurism also persists. With Barbara Morgan’s “Nancy Newhall,” observing her portrait feels as if I am interrupting a moment of deep thought, like obnoxiously slamming the door open on someone’s meditative yoga session. Right next to it is John Gutmann’s “Cynics, Hollywood,” which features two men sharing a knowing yet secretive look, both of their faces cropped close by the camera. Approaching this frame feels like eavesdropping on a moment of secret-sharing between the two men. For a moment, I wonder if the man on the left – who faces the camera in profile – would turn to look at me in irritation, disapproving of my unwelcome observation.

On the east wall is a square of four photographs; from the top row, Edward Weston’s “Carlos Merida” and Ansel Adams’ “A Man of Taos, Tony Lujan” peer down at me, Weston’s with a piercing, inquisitive stare and Adams’ with an atmosphere of untouchable regality. The bottom row features Weston’s “Jean Charlot” and “Eleanore Stone” – both their poses strikingly different yet neither confronting the viewer. The former covers his face with one hand in what appears to be shame and frustration, the glasses behind his fingers slipping down his nose. The latter, on the other hand, poses with a confidence that places the subject almost in the present day. With her head shaved bald, “Eleanor Stone” looks into the distance to the left of the frame, presenting a shadowy profile composed of sharp, bold angles and a charming smirk. She poses with a self-assurance unlike the other subjects of the exhibit who appear tired and worn down by their years.

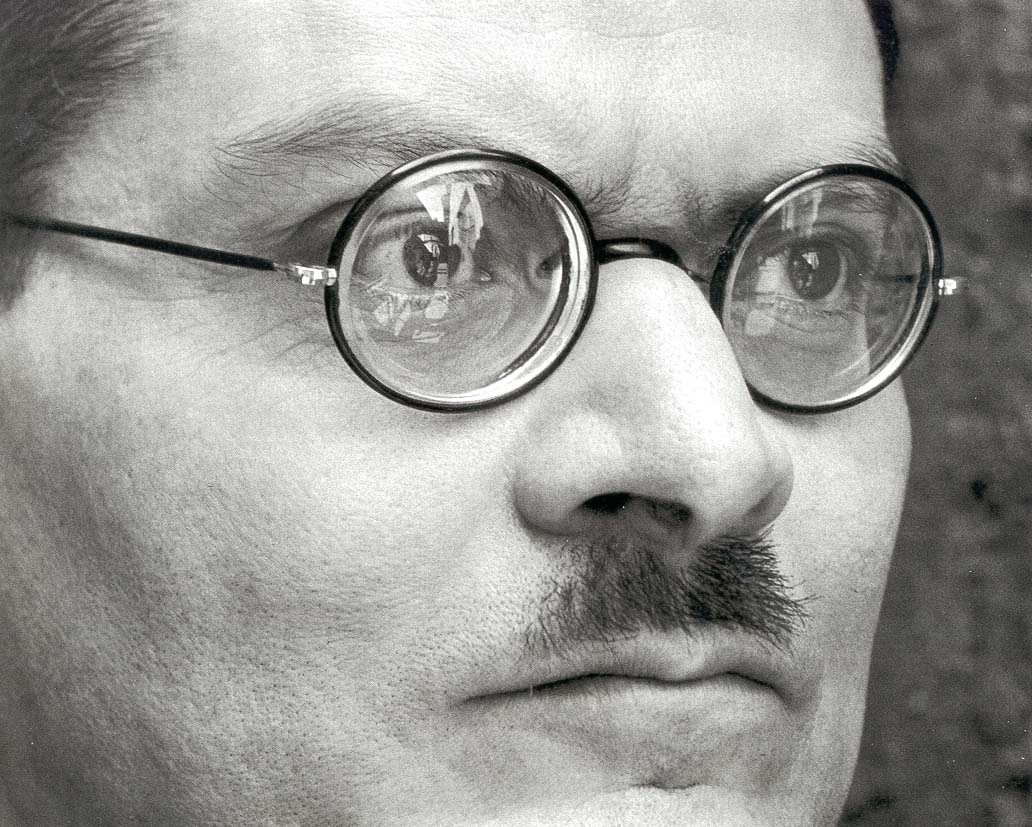

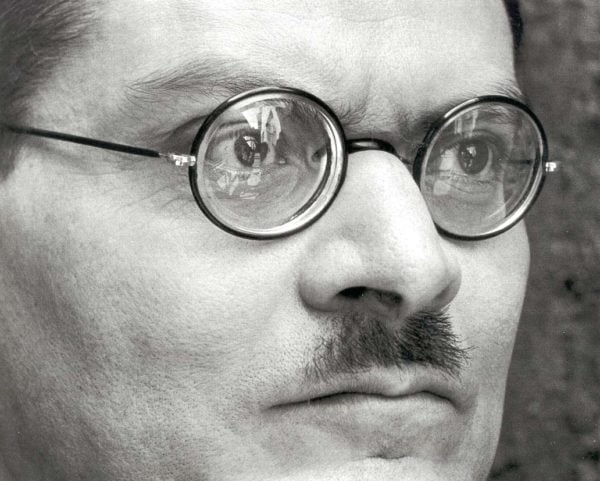

The final wall most notably features two portraits of the same subject and title by Ansel Adams, “José Clemente Orozco.” Both frames display the same photograph, but the one on the right is shrunken and cropped much more than the one on the left. Placed extremely close to the subject’s face, the reflective details of the man’s glasses and the fine texture of his moustache are represented with immediate clarity. Despite knowing nothing of this man, it feels like I am standing inches away from his face. The juxtaposition of the two frames highlights the viewer’s experience with voyeurism; while with the left-hand photograph I am forced to examine the typically ignored details and nuances of the subject’s face, with the right-hand one I am able see my own reflection in the white space. I am confronted not only by the reality of this man but also by my own existence in conjunction with his.

Despite its limited examples, “About Face” is an intriguing examination of modernistic portraiture and contemplative mode of interaction between photography and its viewer. Given the small size of the exhibit, it is more than worth the five minutes it takes to absorb and reflect upon the photographs presented. Plus, it is not every day that you can stare at a stranger’s face for as long as you like.

‘About Face’: Intimacy and Abstraction in Photographic Portraits is on exhibition in the Cantor Arts Center until March 4, 2018.

Contact Julia Gordon at jmgordon ‘at’ stanford.edu .