I recently found myself in a conversation with a friend, who upon reading the online summaries of Vladimir Nabokov’s “Speak, Memory,” deemed them insufficient to match her experience with the text. As an English major and thus deep believer in the power of summary to convey the complexities of the narrative experience, I took this on as an assignment.

So if you — paralyzed by an immense workload and inflexible exercise regimen (I’m looking at you, scholars of the abdominably active Silicon Valley) — didn’t have time to do the reading, here it is: the quick and easy, straight-to-the-point book review of “Speak Memory” — the message of which, I believe, will become quite clear.

Such a commodity is — as I have been informed by my editors — both low in supply and low in demand. (Based on my memory of Mr. Weiss’ economics class, this bodes well for the supplier. Then again, most of my memories of Mr. Weiss’ economics class are overshadowed by the colossal mass of his second chin, swinging gently beneath its upper counterpart.)

Perhaps important to note at the outset is the effect of Nabokov’s writing on the Aspiring Author. His style — rather like the stomach virus that years ago beset FloMo dining — is extremely infectious. Having just finished the memoir, one finds oneself unwittingly falling into lengthy tangents, making fun of one’s high school teachers for no apparent reason and adopting a self-indulgent tone, but all without the literary chops to match. This is to say, please excuse any unwitting parallels in form or content between the book at hand and the review in hand.

And now, if one were to delve into the literary tone, one writing a review (or perhaps an essay, circa 3 a.m., stomach crammed with tepid ramen and steaming self-reproach), might first desire some biographical context.

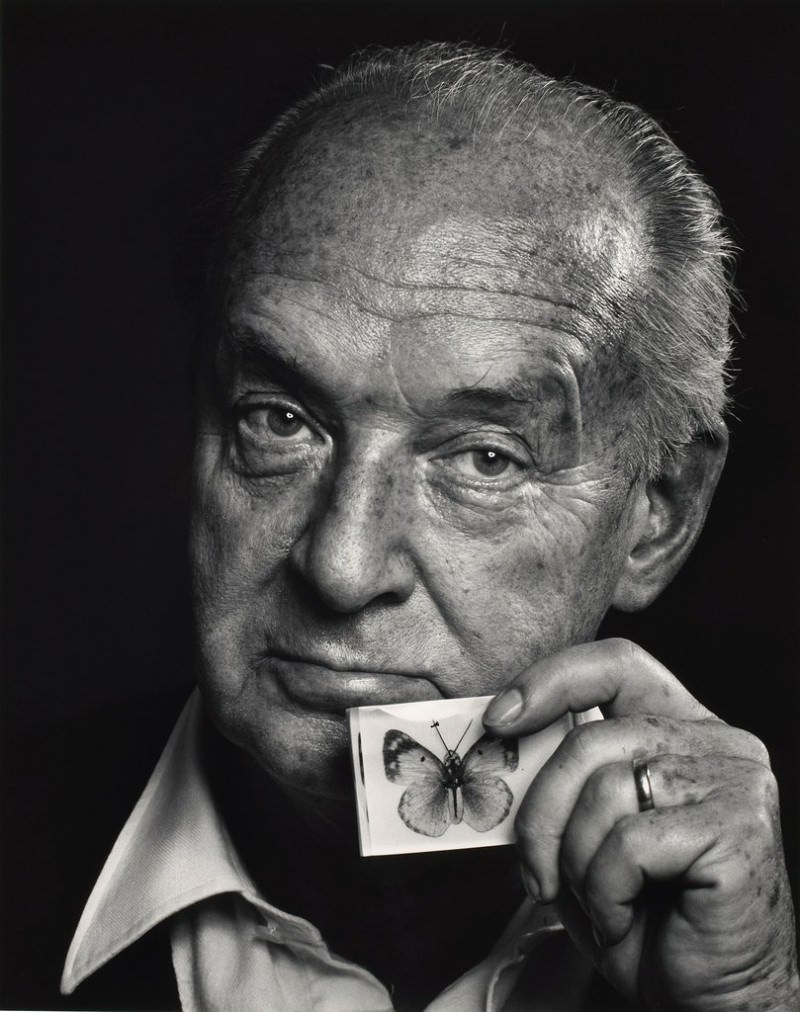

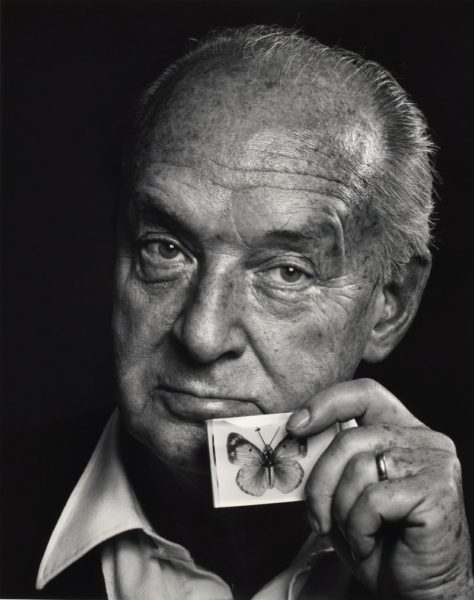

Unfortunately, both reviewer and essayist would be amiss to start on context, which seems like one of the lower priorities on our memoirist’s list. Nabokov lives in a world populated primarily by color. It is possible that the reader, in her investigation of the digital humanities, has stumbled upon the novel: “Nabokov’s Favorite Color is Mauve.” However much of “Speak, Memory” affirms this statistical finding, the autobiography provides a world resplendent not only in mauves, but uliginose textures, speckled surfaces, white lacery and visual details from which Nabokov hops — one to the next — like a butterfly between lily pads.

So extensive is the author’s relationship to color that he spends an entire chapter detailing the specifics of his synesthesia. Thus, Chapter Two comes to resemble a family web of Biblical proportions (and then Mauve had two sons, Taupe and Chartreuse, who were married to Violet who birthed a man of xanthic disposition and each lived for “but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness”), which is nothing to say of the actual family history that follows.

On the actual family history, I will say nothing except that Nabokov’s father was a prominent liberal politician who died when trying to protect an opponent from assassination. Their relationship (not unlike certain friendships forged in the dingy corridors of Cardenal) “was marked by that habitual exchange of homespun nonsense, comically garbled words, proposed imitations of supposed intonations, and all those private jokes which is the secret code of a happy families.”

Despite his father, and despite living through both Russian Revolutions, and despite possessing an identity molded by his role as an emigré writer later in life, Nabokov is more preoccupied with “the yielding diaphanous texture of time” or the imaginative possibilities bestowed upon the artist by the white colored pencil (“that lanky albino among pencils”) than with the events of his country, which he mentions primarily as they interrupt his life. An aesthete of extreme proportions, he treats politics like I treat the Graduate School of Business: to avoid at all costs.

As to his life, it seems to consist primarily of childhood. In these nostalgic digressions, one might catch a glimpse of a nymphet to prefigure Lolita, a “portrait of an old French governess … once lent to a [character] in one of his books,” and a general air of disdain.

That is not to say that moments of humanity don’t slip through his misanthropy. Near the end, he speaks of his “couvade-like concern” for his newborn son. He continues, addressing his wife, “You remember the discoveries we made (supposedly made by all parents): the perfect shape of the miniature fingernails of the hand you silently showed me as it lay, stranded starfish-wise on your palm; the epidermic texture of limb and cheek, to which attention was drawn in dim faraway tones, as if the softness of touch could be rendered only by the softness of distance.” He embraces his son with words of tone and tissue, thus welcoming the child into the sensory world that has characterized his own life.

In the few words the author reserves for the time between his own and his son’s childhood, Nabokov proclaims that the single practical event of his life is securing an Honors degree, approximately equivalent of a Bachelor’s. Now I take a brief pause to address the young academics among us: may you, from your conveniently located yet inhospitably sterile Munger Apartment, breathe a rare sigh of relief.

More than any life event, it is Nabokov’s language that strings his life together. Jargon of the lepidopterous variety suffuses the book like a new color; it is elusive, requiring a dictionary, or an extensive and eclectic vocabulary, or else a different kind of reader: not one in search of complete knowledge, but who enjoys the way the words swirl around each other; Nabokov creates a world not of visuals tied to their inky signifiers but rather a world made entirely of ink, of sea-like sentences rolling off the tongue in undulating azure.

His metaphors are stories in themselves, dark figures beckoning you toward a crevasse, down whose rocky crags you find yourself slipping; any thought of the past — that stable ground from which you began this descent — crumbles with the rocks beneath your feet until he (the author) slips beneath you a platform, the abrupt stability for which you feel so much relief, you don’t even realize that you have been transported to a new (and exasperatingly alliterative) setting, complete with lurid dwarves, mauve imaginings and, perhaps, a beloved daschund.

And sometimes there are one or two lines

In the form of little rhymes

Or some French phrase without cause

(Which adds a little je ne sais quoi)

Two final Nabokovian features: goofy wordplay and uncited allusion to texts, people, places, and events foreign — if not alienating — to the casual reader. I would get to these topics, but I see my time here is running low. And, upon reflection, I see that I didn’t get to the message either. Perhaps I should have listened to my editors after all, who warned against embarking on any literary enterprise without the sumptuous curves of three body paragraphs to guide me along the way.

Contact Emma Heath at ebheath ‘at’ stanford.edu.