A five-percent drop in measles vaccine coverage would triple the number of infections in children, according to Stanford researchers. The study analyzes the risk of parents choosing not to vaccinate children who are otherwise able to be vaccinated.

The study, run by Nathan Lo, a Stanford MD, PhD student, and his colleague Peter Hotez simulated mathematical infection rates to make predictions based on diminishing vaccine coverage trends in certain areas.

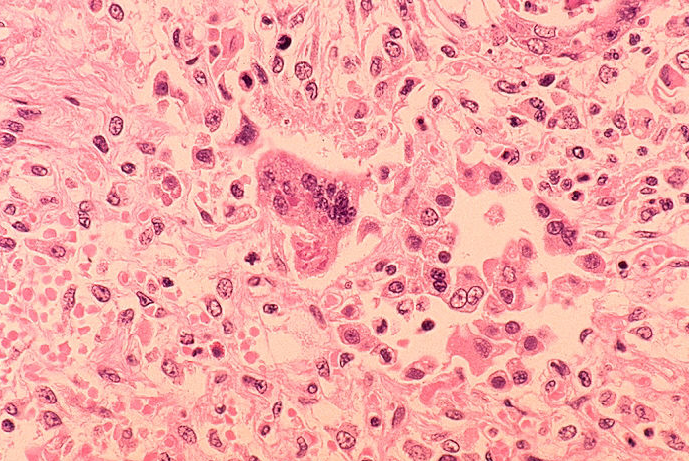

Vaccines give patients acquired immunity through activating the body’s immune response. According to Professor of Pediatric Infectious Diseases Yvonne Maldonado, MD ’81, vaccines reduced infectious disease rates in the U.S. and abroad by over 95 percent, preventing three million disease-related deaths per year.

“[Younger people] don’t see these diseases so they don’t think they’re really around, but they’re not around because we’re vaccinated, so it’s kind of a circular argument,” Maldonado said. “Just because you don’t see the disease doesn’t mean it’s not potentially there, it just means you’re being protected against it.”

According to Lo and Maldonado, measles outbreaks in the US are introduced when infected travelers enter the country. The 2014-2015 Disneyland measles outbreak was caused by an infected overseas visitor who spread the disease to unvaccinated Disneyland patrons. Airborne droplets of measles can last two hours outside the body, making the disease especially dangerous.

Lo chose to study measles because it is a contagious disease. The 90 percent measles vaccination rate in the US is misleading, according to Lo, since the large amount of averaged data points makes it difficult to predict specific outbreaks. Diseases can reach high levels of infection in a mostly unvaccinated area, or not even cause an outbreak if the majority of the community is vaccinated.

Maldonado cited herd immunity as a major factor in outbreak prevention. If one person enters a community of 100 where 99 are immune, the likelihood of the one susceptible person getting infected is low. If 25 people were susceptible, then chances of the infected person spreading the disease is much higher.

“The vaccination levels maybe high in some countries, but it’s such an infectious disease that once it gets into a population of unimmunized people, it spreads like wildfire,” Maldonado said.

Vaccination policies are statewide or sometimes even countywide decisions, according to Lo. All 50 states allow vaccine exemptions for medical or religious reasons, but 18 states allow personal belief exemptions. Lo’s study provided data to state policymakers making these decisions.

“An important step is bridging that gap between the scientific publication and actually reaching out to the lawmakers that are making these decisions,” Lo said.

According to Maldonado, vaccinating as many children as possible is crucial. Leaving children unvaccinated puts at risk children who are too young or otherwise unable to be vaccinated because their immune systems have been compromised.

“There’s no reason for these children to get sick or die from these diseases because we have effective ways to prevent them,” Maldonado said.

Contact Jessica Jen at jessicajen23 ‘at’ gmail.com