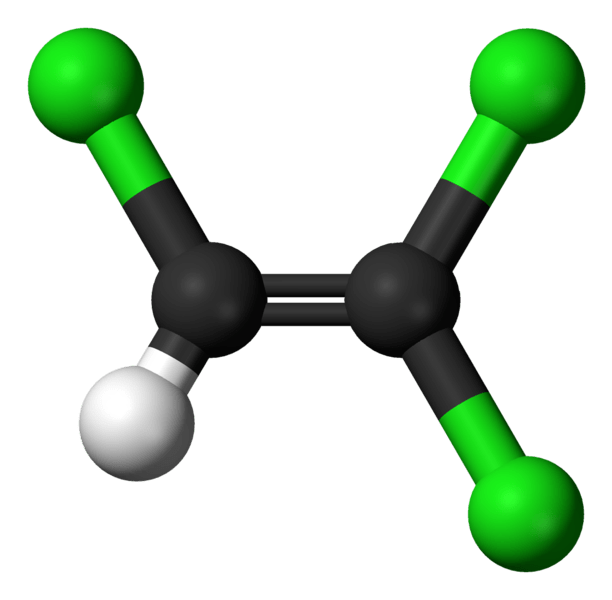

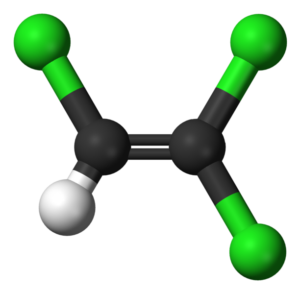

The Palo Alto City Council approved Stanford’s plan to relocate 29 residences near University Terrace — a faculty housing development close to campus — to minimize the risks of trichloroethylene (TCE), a cancer-causing chemical found in the area. The council put forth additional conditions requiring Stanford to install further protections in dozens of the homes near the site as well.

The council’s decision, which occurred over the past two weeks, follows the discovery of high levels of TCE at University Terrace last year. After Stanford submitted a risk assessment to the Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC), several “hot spot” areas with high levels of TCE were identified. Therefore, in addition to the recommendations made by the DTSC, the Palo Alto City Council also called for about 40 homes nearest to those “hot spots” to have a depressurization, ventilation or other form of protection system installed to prevent indoor air contamination.

(Wikimedia Commons)

“It’s a very common approach,” said Stanford spokeswoman Jean McCown. “DTSC, in fairness to them, did not think this was necessary, but the City Council asked that it be added, and we will be doing that.”

Despite these extra precautions, some have qualms with Stanford’s latest plan.

According to Center for Public Environmental Oversight Executive Director Lenny Siegel, who worked as a consultant for University Terrace residents, prolonged exposure to TCE can result in a higher likelihood of cancer and can have particularly adverse effects on pregnant women. Thus, he believes that complete transparency about the issue is critical — and currently lacking.

“Under Stanford’s plan, there was no indication that prospective residents or residents or visitors would know that [the area] is a contamination site,” Siegel said. “My experience nationally is that it’s very important to tell people about contamination. When you don’t and they find out about it, all hell breaks loose.”

The council’s decision comes after months of disagreement between the University and Palo Alto residents over how best to handle the mitigation of TCE in various neighborhoods. Last year, for example, residents of College Terrace — a neighborhood adjacent to Stanford and across the street from University Terrace — independently discovered hazardous TCE levels in six of the 19 homes they examined. This was contrary to Stanford’s assurances that the College Terrace area would not be affected. Concerned that TCE from the University Terrace site may have migrated to College Terrace and other locations, the residents then submitted a report regarding the high levels of TCE in the area to the DTSC for evaluation.

Fred Balin, a resident of College Terrace, believes the Palo Alto City Council should have waited for DTSC to respond to the residents’ findings before making the decision to relocate the 29 residences at University Terrace.

According to Balin, his neighborhood’s findings could have implications for how well the site characterization, or identification of contamination, was performed at University Terrace. Thus, he believes the council’s solution may not sufficiently address the issue.

“It’s definitely premature for the city to let the project go while there is still a potential problem for residents,” Balin said.

Siegel, however, is less opposed to the council’s decision to mitigate TCE levels at University Terrace before making a decision on how to handle the high TCE levels at College Terrace.

“I’m okay with [the University Terrace and College Terrace sites] being handled separately as long as the council recognizes that the initial findings of [University Terrace] indicated that the contamination was more likely to migrate than Stanford had asserted,” Siegel said. “However, there is still a need for Stanford to do additional sampling to determine to what degree the existing homes in College Terrace are threatened by the contamination.”

Contact Shagun Khare at shagunkhare.st ‘at’ gmail.com.