Jet lag can be a traveler’s worst nightmare, occasionally leaving even seasoned globetrotters feeling disoriented and exhausted for days after arriving at their destination.

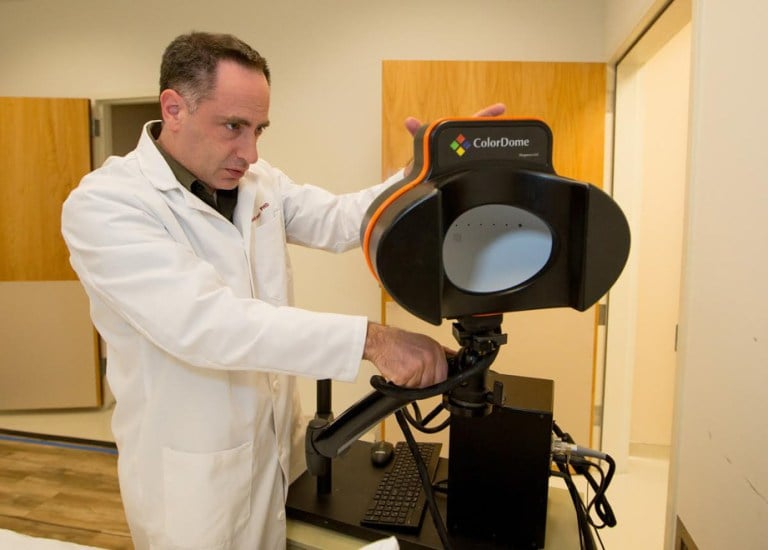

A team of Stanford scientists, led by neurobiologist Jamie Zeitzer, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, are working to develop a method to prevent jet lag. Their technique would not require any medication or adjustment of sleep schedules and would simply transfer light to the brain through the eyes to alter a person’s biological clock.

On its own, a person’s circadian system can take up to one day per time zone traveled to adjust. During this adjustment period, jet lag causes symptoms of malaise and fatigue.

The researchers have found that exposing sleeping subjects to short flashes of light can help people adjust more quickly to changes in time zones. Zeitzer explained that this helps curb the effects of jet lag prior to long-distance trips.

“Our research essentially explores how to better adapt people for modern society, our 24-hour society,” Zeitzer said.

Currently, light therapy treatments require a person to sit in front of bright lights for several hours at a time. This will gradually transition the body’s circadian clock to a new time zone. Zeitzer’s study would instead provide light exposure during the night before a trip. This would allow travelers to maintain a normal daily routine.

“We’ve been exploring with using sequences, very short pulses of light, which is what you would get exposed to with a camera flash,” Zeitzer said. “We found [that] you can expose people to this light while they’re sleeping and it doesn’t change their sleep. They don’t wake up to this flashing light.”

A group of Stanford students have formed a company based on techniques from this technology. Students are involved in one project to create eye masks with LED lights that will flash at the correct time and sequence to adjust the body’s circadian system to a new time zone before a long distance trip.

“The mask will be attached to a smartphone app where you can plug in the time you normally go to bed and where you are traveling to, and it will automatically do the rest for you,” Zeitzer said.

Zeitzer’s research also has implications for high school students who have difficulty waking up for early morning classes.

During childhood, melatonin, the hormone that controls the wake-sleep cycle, is secreted during early evening. When children reach puberty, their melatonin is released later during the night, between 9 and 10 p.m. Though teenagers need at least nine hours of sleep, their new melatonin cycles make it difficult to go to bed early.

Zeitzer explains that as a result, teenagers are often tired during morning classes.

“This shift in melatonin release time means that teens cannot sleep before 11 [p.m.] because biology won’t allow them to do it,” Zeitzer said.

“Our research can provide an environment where we shift the biology which will enable them to go to sleep at an earlier time,” he added.

Zeitzer’s research could provide a more efficient adjustment method for those who experience frequent disruptions to their sleep cycle, such as medical residents and night-shift workers.

Contact at Friend Chaikulngamdee at friendc ‘at’ stanford.edu.