There is no artist in the history of movies that can even begin to approach the skill of Sir Alfred Hitchcock. Looking back at his works, we stand in the shadow of a giant — a director who, more than any other Hollywood filmmaker before his time or since, intuitively understood what cinema is, what it could do and what it should be. That’s why “Hitchcock/Truffaut,” the new documentary by film critic Kent Jones, is such a welcome blast from the past. Though it’s not a revelation for cineastes, it can serve as an important gateway into the mammoth movie-making machine that was Alfred Hitchcock.

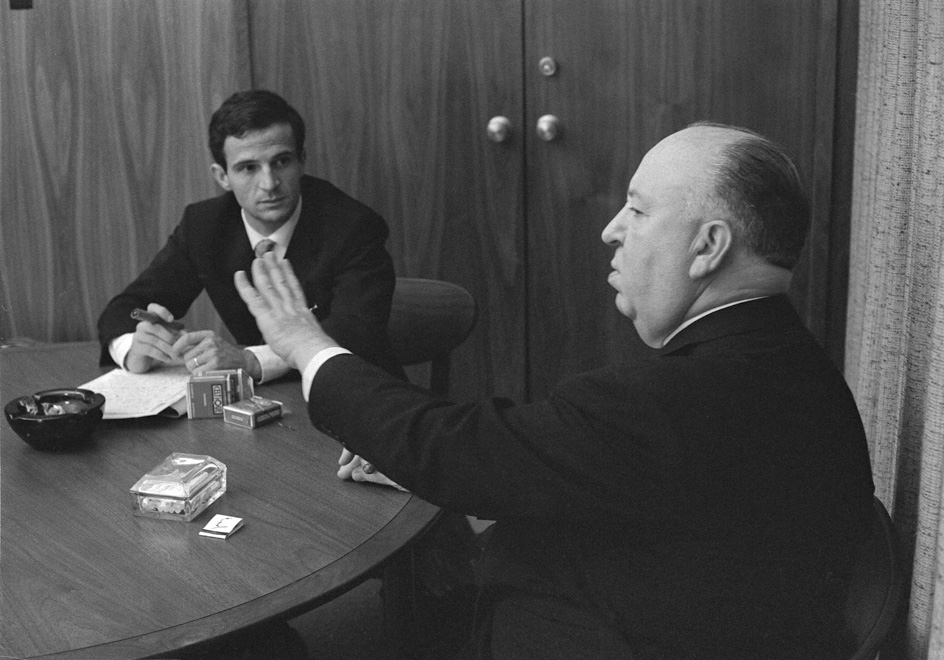

“Hitchcock/Truffaut” documents the famed interviews between Hitchcock and one of his biggest admirers, the French New Wave director François Truffaut. At only age 29, Truffaut catapulted to instant stardom and renown with a string of films released between 1959 and 1962, including “The 400 Blows,” one of the best movies about adolescence ever conceived. When he was traveled to New York, American reporters asked Truffaut to name his favorite director. “Monsieur Hitchcock,” he responded without hesitation. The reporters were shocked: They couldn’t believe that Truffaut, the creator of such serious and mature films, would find value in a commercial hit-maker like Hitchcock, who at that time was merely considered an “entertainer” in America. Thus, the stage was set for a meeting of magnificent minds. Truffaut contacted Hitchcock during his stay in America. He then made arrangements to interview Hitchcock about his life and career, talks which would be recorded, transcribed and released as a book. Hitchcock, flattered that a critic took his work as seriously as Truffaut did, immediately accepted the proposition. Over the course of a few months in 1963, Truffaut and Hitchcock bantered about film, art and life, aided by their English-French translator Helen Scott.

Kent Jones, the doc’s director, spends much of the first half detailing the cultural impact of the resulting book, which was first released in 1966. People by the likes of David Fincher and Wes Anderson pop up to detail their admiration for it. Much of the middle half is devoted to selected analyses of Hitchcock’s works, including Scorsese’s analysis on the psychological underpinnings in “Vertigo,”Hitchcock’s most beautiful film.

None of this information is particularly revelatory to film fans. The middle chunk’s goal is to cement the legitimacy of Hitchcock’s oeuvre, but it doesn’t seem as though it’s a task worth pursuing in a day and age where the name Hitchcock has become synonymous with “great director.” The best this documentary can do is introduce younger viewers to the name of Hitchcock, of which “Hitchcock/Truffaut” does an admirable (if repetitive) job.

At the cost of learning a lot about Hitchcock, we don’t get enough insights into the other two partners in this spicy cinematic threesome. Truffaut, despite being half the title, remains all but untouched. It would be interesting to see how Truffaut’s and Hitchcock’s styles of film converge and reflect one another, especially since the former openly admitted he was a disciple of the latter. Instead, Jones denigrates Truffaut’s mighty oeuvre of films (“Jules and Jim,” “Shoot the Piano Player,” “Day for Night”), pegging him as a “non-stylist” in a way that shouldn’t sit right with the knowledgeable viewer. And we learn almost nothing about Helen Scott, the woman who served as mediator between the English-speaking Hitchcock and the French-speaking Truffaut. So many questions spring up that Jones plain refuses to investigate. How did she get contracted to serve as collaborator between these two giants? What were her thoughts on film? Was she a fan of either director’s oeuvres?

Yet with all it ignores, “Hitchcock/Truffaut” still manages to spark new interest into the works of an unequivocal master of cinema. There are many people reading this right now who may have never even heard, much less watched, masterpieces like “Vertigo,” “Rear Window,” “Strangers on a Train,” “Notorious,” “Shadow of a Doubt,” “The Birds,” “The Man Who Knew Too Much” and so many other films by Hitchcock. Kent Jones, for all the hiccups he encounters in his first stab at filmmaking, manages to excite the inner cinephile in all of us. For when we crave more than the offerings of modern cineplexes, we can turn to handy-guides like “Hitchcock/Truffaut” (both the documentary and the book) to guide us to movie heaven. Hitchcock’s and Truffaut’s films will never go out of style, for great art can only age like fine wine.

“Hitchcock/Truffaut” is a solid companion piece to the superior interview book of the same name. Given its two prominent collaborators, it’s worth a look. It manages to reignite interest in a man who redefined cinema almost singlehandedly and it does so through the deadliest of passions: cinephilia. When you’ve got it, you won’t ever be rid of it.

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.