A report recently published by the Economic Policy Institute suggests that United States schools may not be trailing behind those of other countries as much as previous studies have suggested.

The report was authored in part by professor of education Martin Carnoy, an economist specializing in education who has been a professor at Stanford for more than 40 years. The report analyzes international results of two assessments, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). It focuses on the usefulness, or lack thereof, of common metrics used to compare the U.S. with other countries in order to make conclusions about the relative statuses of international education systems.

“This report is essentially a continuation of an earlier report, which analyzed the results of the PISA and TIMSS tests in the U.S.,” Carnoy said. “But this time, we focused heavily on individual states. Our main idea is that the U.S. as an educational system doesn’t really exist; it’s really at least 51 separate systems [including each state and the District of Columbia].”

Carnoy emphasized that comparing average test scores across countries ignores students’ family backgrounds; in other words, test scores might not provide an accurate measure of the quality of education.

“The test scores themselves measure an aggregate of a lot of effects: family background, inequality of schooling and extracurricular commitments,” Carnoy said.

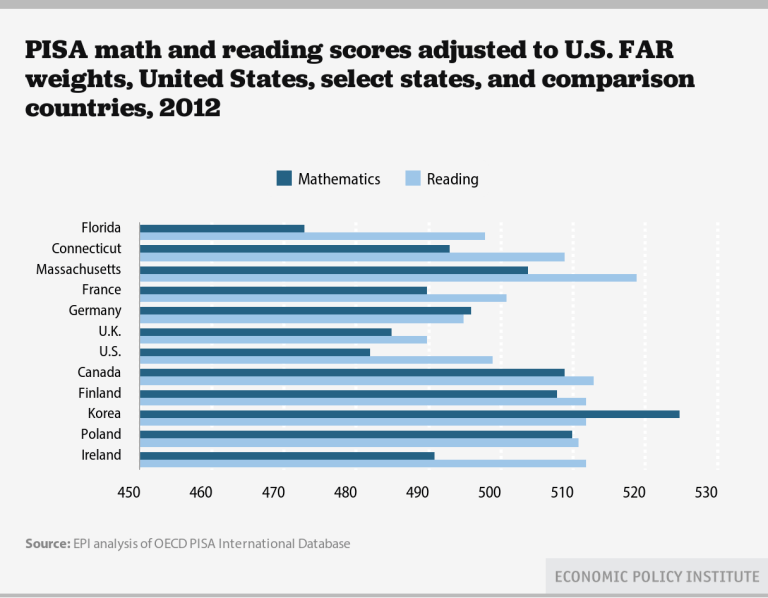

With this in mind for the report, Carnoy further broke down test score numbers to consider the backgrounds of students for a more accurate reading of data, using the number of books per home as a proxy for showing how much a family is focused on academics. Adjusting for such family academic resources reduces variation between the U.S. and other countries in reading by up to 40 percent and in mathematics by up to 25 percent.

“The U.S. has one of the highest poverty rates among developed countries, and so the samples from the U.S. reflect that difference,” Carnoy said. “We have a lot more poor kids taking these tests. Adjusting for that, the U.S. does somewhat better.”

While controlling for students’ backgrounds does reduce variation in scores when comparing the U.S. to other countries, Carnoy argues that it is still rather fruitless to make these nation-by-nation comparisons in the first place.

“The educational and social cultures among countries vary enormously, and that variation is a lot smaller among U.S. states,” Carnoy said.

One example he touched on was the comparison between the U.S. and South Korea. Korean scores are greatly influenced by the fact that students often attend cram schools, where they study for the purpose of improving scores. Thus, the high scores in Korea do not necessarily reflect the quality of the education Korean students receive at at standard schools.

“On the other hand, we have models in the U.S. that can help us understand what works in terms of improving education,” Carnoy said. “Looking state by state, we have a much better chance of looking at the numbers we’re getting to figure out which levers to pull in education to improve it.”

In order to find those levers and to improve education, Carnoy is actively researching the processes and standards that differentiate top-scoring states, like Massachusetts, and lower-scoring states, like California.

Stanford professor emeritus of education and business administration Michael Kirst, who is also in his fourth term as president of the California State Board of Education, found Carnoy’s report to be both insightful and helpful as he continues to engage in work surrounding the improvement of California’s education.

“This is a very informative and unique analysis,” Kirst said. “I think a lot of international organizations like the OECD have been making claims about U.S. education and how to reform it without truly understanding it, and this will help get us on the right track.”

Kirst is hopeful that Carnoy’s findings will help yield concrete practices so that people are less focused on borrowing from international school systems and more focused on improving California state education, which is more accurately compared to that of other states.

“The California to Texas comparison is much more relevant than the comparison between California — with almost 40 million people and 6.3 million students in public school — and Finland — with a total population under 6 million,” Kirst said. “[International comparisons] push policy action to the federal level when it’s better off being tailored to each state’s unique context.

“Our job as a state board is to dig deeper into the differences between California and other states, and that’s what we’re planning to do,” he added.

Contact Susannah Meyer at susannahmeyer ‘at’ stanford.edu.