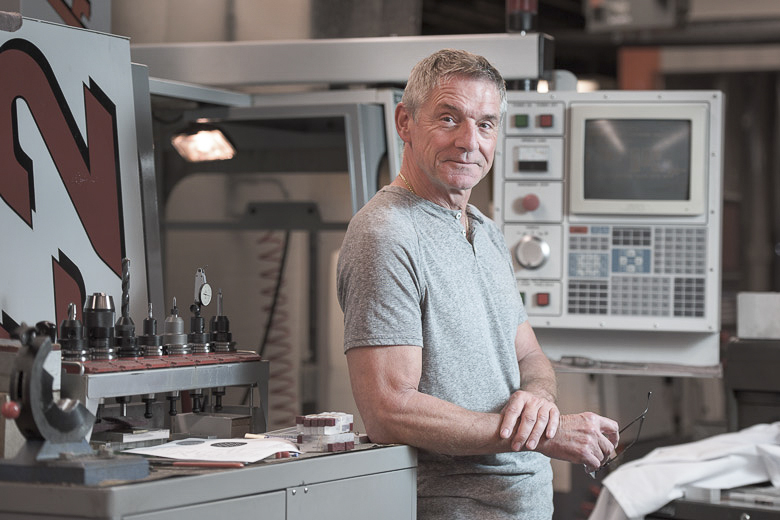

Karlheinz Merkle, supervisor of the Physics Machine Shop, recently received the 2015 Marsh O’Neill Award For Exceptional and Enduring Support of Stanford University’s Research Enterprise.

According to its website, the shop offers design assistance or complete project development — moving from blueprint sketches to actual construction through welding, brazing and soldering. The shop features a CNC (computer numerically controlled) mill and lathe, as well as electro-discharge machining. These technologies allow the shop to design shapes beyond what is possible with more conventional machines.

In his role as supervisor, Merkle is officially responsible for ensuring that the shop’s machines function properly and that the lab’s budget is maintained properly, according to Giorgio Gratta, a professor in the Department of Physics.

“In practice he also works with the machines himself, and he’s also very good at actually advising people and helping them design things that they need,” Gratta said.

Merkle’s history with Stanford goes far back: He began working at SLAC in 1983, when a new storage facility opened up there. In 1998 he joined the Physics Machine Shop and has been there ever since.

Merkle said that over his years at the shop the work has become more sophisticated. For example, individual atom manipulation was not done when Merkle first arrived in the shop but has emerged during his time here.

“There are still things that we could not do in that scale [in the past], but we have now all the CNC equipment that you need for today’s fabrication,” Merkle said.

The award came as a total surprise to Merkle, who says that he heard of the news after returning from a vacation. An award ceremony was held on Nov. 16 at the Faculty Club: speakers included physics department chair Peter Michelson, physics professor Blas Cabrera and Merkle.

“My kids were there; some friends were there and then [also] staff, my colleagues and the faculty,” Merkle said.

Merkle said the shop is always faced with challenges because the jobs they take on always concern something that hasn’t been done before. He noted that his work is highly cooperative in nature.

“A lot of times it takes a collective mind, not only myself but the staff — that we will have to say ‘OK, how are we going to approach this the best?’” Merkle said.

One particularly challenging project Merkle remembers was the Enriched Xenon Observatory (EXO-200). According to Gratta, the EXO-200 is a very large particle detector, the creation of which involved collaborators from several countries. The largest and most critical components of the project were fabricated in Stanford’s Machine Shop, largely due to its reputation.

“It is an excellent shop, and everyone [involved in the project] recognized that,” Gratta said.

According to Gratta, the components were mainly designed by non-Stanford engineers, but Merkle designed a number of features and auxiliary parts used while building the detector.

Looking forward, Merkle said that the direction the lab takes in the future will be determined by the scientists whose work is realized there. Although Merkle noted that the lab may need to acquire machines with new capabilities as time proceeds, he believes the shop is generally prepared to deal with most of what it will face in the future. This is especially true because the shop mainly deals with plastics and metals, he explained; other materials are handled by other Stanford establishments like Stanford’s Crystal Shop, which works with crystalline or amorphous materials, or off-campus providers.

According to Merkle, the shop does work for a variety of places in the University and beyond, including the hospital and the School of Medicine. He explained that this ensures that there is always something going on.

“It’s a fun job at the end, because you meet a lot of new people, young people, constantly,” Merkle said.

Contact Skylar Bromley Cohen at skylarc ‘at’ stanford.edu.