The Oregon loss was not fun.

Okay. I think we’ve established that the Oregon loss was not fun.

But Instant Replay goes on, win or lose. Look, if my favorite ever non-Stanford player, Matt freakin’ Barkley, can release a video breaking down film three days after he lost to Stanford for the fourth straight time, I can diagram a couple plays for a game that I didn’t even play in.

Yeah, I think Stanford ought to have won the game — when was the last time Stanford ended more drives with fumbled snaps than punts? But that’s just football, and Stanford needs to do a better job taking care of the ball. The loss was fully deserved. When both offensive lines are owning the line of scrimmage and touchdowns are raining down all over the field, the game’s going to be decided on turnovers, and Stanford had more of them.

So let’s get down to the pain. Oregon’s offensive dominance in the trenches can’t be reduced to a single play, but if I have to pick one play that crushed the Cardinal, it would not be a run play but a pass: the post-wheel curl. It’s a sexy play, if you have the pass blocking for it (this is typically true for any five-receiver, empty-set pass play), and Oregon’s offensive line decisively outplayed the Stanford front seven in both the passing game and the running game. This play led to not one but two Oregon touchdowns.

***

What is the post-wheel-curl? It’s a concept that floods one side of the field with receivers while stretching the defense vertically by putting receivers at multiple levels of the field. The post goes deep, the curl typically breaks back to the QB at an appropriate distance and a wheel route gives the team an emergency option in the flat. It’s a slow-developing play, so Oregon likes to run the PWC in combination with “Mesh,” the old Mike Leach mainstay (two shallow crosses) in order to get some built-in hot routes against blitzes. Oregon is betting on itself: that its offensive line can buy QB Vernon Adams a few seconds and that Adams’ speed can buy himself a few moments after that.

The first read is almost always the curl, but against man coverage, typically the wheel comes open, and against zone coverage, the curl or post should come open — they look similar and run parallel to each other, but then they break off in different directions, stretching the defense.

Let’s take a look at the first time Stanford gave up a TD on the PWC.

The Oregon formation looks like a run

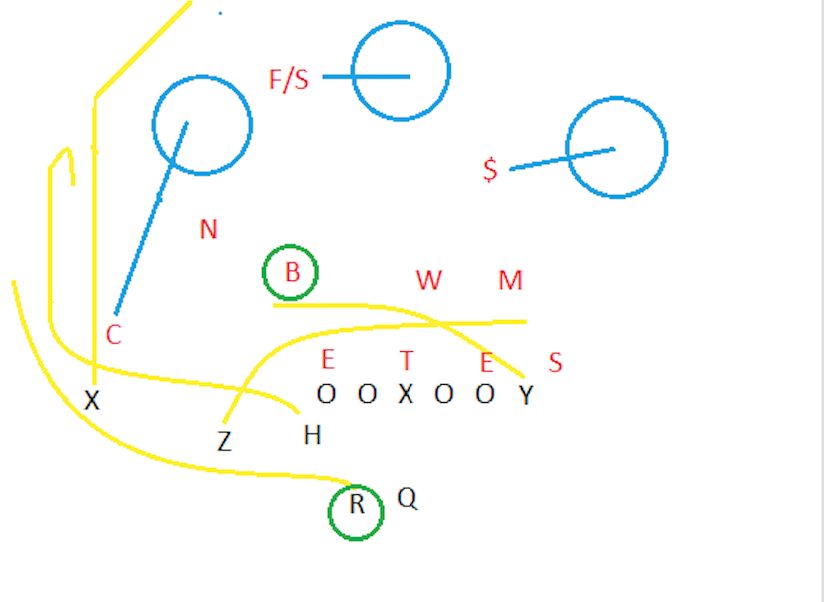

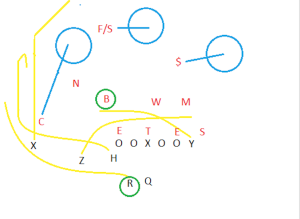

The Cardinal are in a zone defense. Blake Martinez (B) is green-dogging: Essentially, he blitzes if the running back (R) pass protects, and he takes him man-to-man if he runs to pass. He defends the wheel very well. Quenton Meeks (N) is the flat defender but follows H vertical; as Stanford defensive backs are coached, he gives H a wide cushion, to the point where actually looks like he’s settling in a deep zone himself. Backtracking towards the middle of the field and faced with a receiver flood, Alijah Holder (C) and Kodi Whitfield (F/S) appear to have a miscommunication: Holder initially follows Darren Carrington (X) upfield but trails him and settles in a zone, clearly expecting Whitfield to take the post. But Whitfield doesn’t actually take the post — live, it looked like he gave up on the play. Carrington walks into the end zone and Oregon takes a one-point lead over the Card.

On to the second play. Stanford’s now down by five points. The Oregon offensive line has been winning its battles against Stanford’s base defense seemingly all game, and Stanford defensive coordinator Lance Anderson — a pressure coach first and foremost — wants to free up players to bring blitzes and crash the run. Consequently, the Cardinal aren’t running zone coverage anymore. This is standard man-under — one safety deep, man coverage on the receivers.

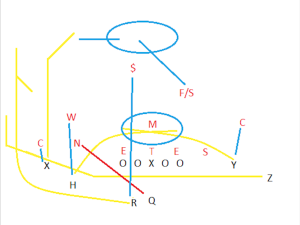

Oregon confuses Stanford by switching up the routes, running the curl with running back Taj Griffin (R) and simulating a wheel with a jet sweep by Z. It’s still essentially the same look for Oregon’s Vernon Adams — the post, the wheel and the curl — but it makes things harder on the defense. Meanwhile, Stanford doesn’t know what’s going to happen, but it does know that it wants a nickel blitz (N).

When Z goes into the jet sweep, Stanford doesn’t send its cornerback on the right across the formation — it simply switches the assignments in the secondary. This is more difficult than it sounds, but Stanford actually does it pretty well. Of note is that strong safety Justin Reid ($) comes in from deep — whatever the other changes were, when Stanford adjusted to the jet, Reid and Whitfield (F/S) switched responsibilities. Reid was originally the deep safety. This will become important later.

A positive note first. There’s nobody to take the jet wheel at first, but Blake Martinez (W — yes, I know Martinez is a middle linebacker) passes off H as soon as he realizes H is only on a shallow cross and takes Z in the flat instead. (That’s two for two for Martinez on these plays. Well done.)

Oregon’s offensive line does a marvelous job of reading the defense and sensing the blitz, and because Adams’ earlier running has forced Kevin Palma (M) to sit back in a spy technique to defend against QB scrambles, Stanford’s only got five blitzers against five blockers. Adams has plenty of time, even though Stanford set its edge rushers extremely wide to get better angles at him.

The play unfolds extremely well. I want you to focus on Carrington (X). He might have scored on the previous PWC, but he’s no prima donna wide receiver: He’s willing to do the dirty work here, and he does a marvelous job of running interference against Stanford’s defensive backs. When Reid — remember, he had to switch from the deep safety to man coverage on Griffin — overcompensates and crashes too close to the line of scrimmage, Carrington notices this, and when Reid tries to recover towards Griffin, Carrington essentially screens Reid out of the play. It’s a freshman mistake, and because Carrington knows what he is doing, a very costly one. Stuck in the middle of the field with nowhere to go, Reid desperately tries to bat the ball away, but Adams makes a nice, arcing throw that Reid doesn’t have a prayer of picking off. There’s still Whitfield deep to save the day, but Carrington basically “runs” his post route right into him. This is all legal, by the way.

Griffin’s now at the Stanford 30 with nobody in front of him. The result: pitch, catch, touchdown Oregon. Carrington’s effort is one of the things that makes it so difficult to play man against the PWC — the deep routes make it so easy to set picks for the sideline curl if it’s coming from a place like the backfield, when the defender has to set up in the middle of the field. A+ work for Carrington on both pass plays, and that’s not grade inflation either. Darren Carrington: so nice, Oregon used him twice.

The plays I’ve broken down aren’t run plays. But their effectiveness is directly related to the effectiveness of the Oregon offensive line as a whole. The first play looked like a lucky play call, but really it was the perfect way to attack an adjustment that Stanford felt was necessary because of how successful Oregon’s base run game had been. The second play took advantage of the fact that Stanford had to bring the blitz against the Oregon offensive line. Well done to the Oregon offense. The Ducks pounded Stanford where Stanford prides itself the most — the trenches — and they looked really, really good doing it.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.