[Correction: Kevin Hogan’s two big runs were not both read-option Power plays. One of them was in fact a traditional Power read; the other looked like it was a QB Power, where McCaffrey went wide for a potential toss or screen pass, and Kevin Hogan read the safety to see whether to keep or run. I find this mistake quite embarrassing and I will do my best to make sure similar mistakes don’t happen again.]

This was the sort of game where the only thing you can really say is, “Stanford found a way to win.” I hate coaching clichés and “we just found a way to win” in particular, but to be honest, there aren’t very many rational ways to explain how Stanford won the game. It was basically just red zone defense. Stanford didn’t really excel in any area of the game except the toughness department.

Partly because it’s hard to identify something interesting, I’m not going to diagram a play today. Let’s talk about the finer points. I’ve only gone text-only on Instant Replay twice before — 2013 Cal, where Stanford ran pretty basic plays and Cal simply had no idea how to defend them, and 2014 Oregon, where Stanford actually threw the kitchen sink at Oregon to such an extent that it was more interesting to try to cover them all.

This game was different. This was the sort of football game that is wonderful if you are actually playing and makes you want to drink bleach if you’re not. It happens. No point in getting too enraged about ugly wins against decent teams.

***

First off, most of you will be asking about Kevin Hogan’s two big runs. Fair enough — without these runs Stanford loses the game. Washington State was extremely aggressive on the blitz and keyed in on Christian McCaffrey all day, which made the read-option a good idea — because option plays give you extra double-teams in the running game, it’s hard to design blitzes that are option sound. In response, Kevin Hogan ripped off two gigantic gains on the Power read-option — one of David Shaw’s go-to plays, and therefore very much an “in case of emergency” call. Was it an emergency? Stanford ran 59 plays for 312 yards, and 98 of these yards came on these two option plays. You’re darn right it was an emergency.

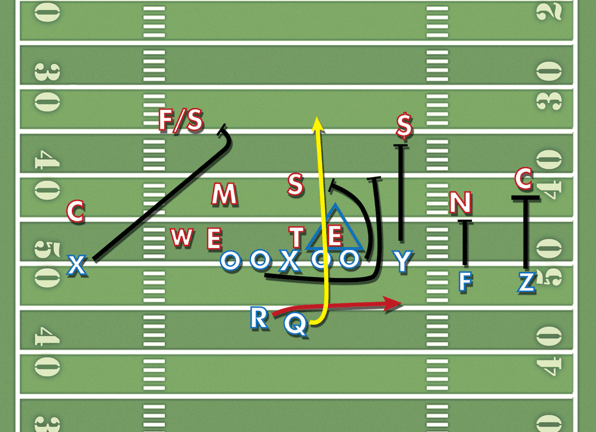

This is the Power read-option. I’m posting the graphic from the 2013 Oregon game so you can get a good look at it. The defensive alignments on the two Hogan explosions were, of course, very different.

Yes, the starting linemen just didn’t look very good, with one exception (who will go unnamed in this column). To be fair, they were up against a Cougar squad that was more than happy to blitz and shoot gaps in a very devil-may-care fashion. And that’s why Hogan was so effective on the read-option — because that’s what the read-option does. It eats blitzes alive. But with Hogan wearing a knee brace, it’s understandable that David Shaw didn’t want to go full Oregon and run the zone read on 50 percent of plays. And in the midst of a California water crisis, it’s also understandable that on a rainy evening, Stanford’s passing game ground to a halt.

***

Yes, Stanford was absolutely superlative on red zone defense. But Stanford shouldn’t have been forced to defend in the red zone so many times in the first place. It was only in the red zone so often because Luke Falk marched up and down the field.

Stanford got burned all day on comebacks. You may feel tempted to blame the cornerbacks, but this happened to Alex Carter all the time too, and he plays on Sundays. Stanford has been giving up comebacks for years. It’s what Stanford’s coaches are willing to give up, because intermediate-to-deep passes to the outside are difficult to complete. And normally Stanford’s defensive backs can recover quickly enough to break up the pass because most quarterbacks don’t have the superlative timing of Luke Falk.

Falk’s performance shows why Mike Leach barely bothers to run the ball: The less you emphasize the run, the more practice time you can devote to making sure the passing game is absolutely perfect. Washington State rarely got its deep threats wide open, but there’s a difference between NFL open and college open, and there were plenty of times when Falk only needed his receivers to be NFL open. I don’t think Stanford got convincingly outschemed on defense, but Leach wanted timed comebacks and one-on-ones, and he got his timed comebacks and one-on-ones.

That’s pretty difficult, and most people don’t realize that — which is why people so often assume that a quarterback that rips college defenses apart will be successful in the NFL. NFL players need to make NFL throws. And while I think NFL scouts won’t like Falk’s footwork — timing in college is about chemistry with receivers, while timing in the NFL is all about footwork — Falk can certainly make NFL throws.

***

On special teams, Christian McCaffrey’s reign of terror was never going to last, because teams were always going to end up trying to neutralize him. They were going to kick it low, away, short, whatever it took to stop McCaffrey from getting a head of steam. It’s exactly what happened to Stanford’s last All-America-caliber returner, Ty Montgomery. It will continue to happen.

WSU was willing to give Stanford 10 extra yards of field position on every drive just to keep McCaffrey from returning the ball; McCaffrey’s threat alone generated 40-50 extra yards every game. But that’s football for you. It’s always a chess game, and as long as the rules remain even reasonably equal toward the offense and the defense, there’s never going to be a game-breaking concept. There will only be game-breaking players. Stanford’s got some of those.

***

If you have time, take a look at Aziz Shittu’s sack of Falk for -11 yards — one of the few plays that might have been worth a column. Solomon Thomas puts up some seriously good technical work on top of the screen, Mike Tyler bull-rushes the left tackle into the next century, Martinez runs a nice little stunt for a looping Shittu, massive pressure stops Falk from completing an easy pass to an open running back and Shittu fights through half the offensive line for a game-saving hustle sack.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.