Stanford is pretty good at this football thing, no? Washington does a tremendous job of playing team defense, and yet Stanford racked up 478 yards against one of the country’s better units. And while Stanford has beaten teams with flash and thunder this season — blowout after blowout after blowout — Saturday was a different kind of win, a vintage Stanford win. You know, the kind of win in which Stanford owned the clock, choked the opposing offense into submission and slowly ground its opponent into the dust. The game never felt like a blowout, but then you raise your head, stare in disbelief at the score and realize that Washington lost the game at kickoff.

For online viewers, let me preface this breakdown with a note. I typically try to use this column to highlight points that I think the other football writers have missed; reviewing the UCLA game, for example, I insisted on covering the offensive line because I thought it needed more love, considering how dominant it was. But at the same time, I’m only going to cover plays that I can give you video for, and the videos out there for the Washington game leave a lot to be desired.

In particular, the chess match between the Washington offense and the Stanford defense was woefully ignored. Defensive coordinator Lance Anderson called some extremely attractive defensive line stunts to generate four-man pass pressure — the goal of every defense — but apparently pressure only counts as a big play these days if you actually get the sack. K.J. Carta-Samuels was running for his life most of the second half but only got sacked once.

On offense, the issue is different — big plays that aren’t really coverable. There were, obviously, some absurd feats of skill by Stanford’s backfield, but you can’t really break down these plays. All you can do is sit back and marvel. And Christian McCaffrey’s 50-yard TD reception came off a pretty cool wrinkle on play-action Power (seriously, watch it), but there are only so many times that you can look at variants of Power before readers start to get bored.

I’m going to cover a successful Washington play today. I want to make it clear, first of all, that covering a Stanford defensive breakdown is not meant to be representative of the Cardinal defense on Saturday night. Stanford played quite well on defense and repeatedly overpowered Washington’s offensive line when it mattered most. But this play is worth a second look.

I love a good counter run, I love a good trap play — imagine how much I like watching a good counter trap. All football coaches steal from each other (as Chip Kelly once put it, “If you weren’t in the room with Amos Alonzo Stagg and Knute Rockne when they invented this game, you stole it from somebody else”), and this one has been around for a long, long time. The reason it’s never faded away is because it’s just a really darn good play. And running back/space alien Myles Gaskin made Chris Petersen and company look real, real good for calling it. (Video, as always, can be found online; fast forward to 1:00.)

At this point you’re probably asking what exactly is a counter trap. Jon Gruden did a great job of explaining the components of the counter trap on his TV show, but we need to understand why you would run a counter in the first place. A counter play is where you fake a move to one side of the formation and then run to the other side; naturally, you run it when you think the fake will get the defense badly out of position. A trap is a type of block in which you initially leave a player unblocked and then pull a blocker out of the formation to sideswipe him as he rushes forward. It’s really good against aggressive front sevens, and in particular really punishes pass rushers.

Intuitively, you can see that the basic concept of the counter and the trap work extremely well together. The counter trap doubles down against aggressiveness and viciously punishes mistakes. It’s an excellent play, and one that teams across the country run at every level. Lance Anderson wanted Stanford to be aggressive and generate pressure against the sophomore Carta-Samuels. For the most part the plan worked, but here Washington blocked its way to a massive 28-yard gain that set up its first score of the night.

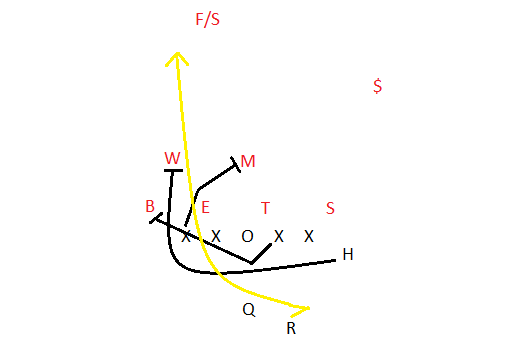

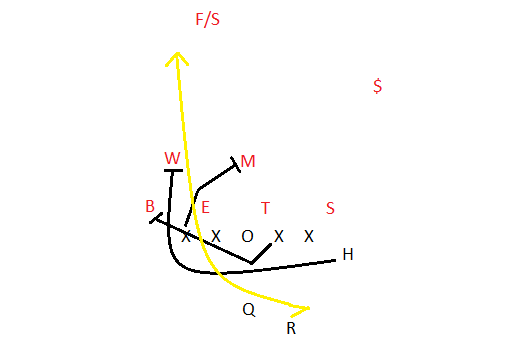

Before the snap, Washington improves its chances of a successful play immensely by motioning an extra man from the slot into the box (H). The H-back was covered by a strong safety ($), but he didn’t enter the tackle box in response — likely because of his coverage responsibilities. Washington consequently has six blockers against six defenders in the box, and it can now start calling physical running plays. Huskies head coach Chris Petersen loves using motion to generate favorable matchups, and he got Washington a big advantage in the run game before the ball was even snapped.

We’ve discussed the components of a counter play: How did Washington put these components into practice? Petersen designs a nice little counter action: Gaskin turns to the right as though he’s leaking out for a screen pass. Back in the day Tom Osborne’s Nebraska — kings of the counter trap — would have faked a run to the right and then cut back for the counter. Now because offenses are blurring passing and running more and more, the threat of a screen is similar to the threat of a run. (The basic concept of the play barely changes, but in general, innovation in football comes from the architectural wrinkles every new generation adds. My favorite example is Urban Meyer’s Florida; he ditched the tight end, pulled the right tackle, used the running back to seal off the backside and brought wideout Percy Harvin from the slot to run the ball instead.) Today, when you’re employing misdirection, the direction of the fake matters more than the type of play you’re trying to fake.

Now it’s time for Washington to attack Stanford’s aggression. Stanford’s four players on the line are aligned in an Under front (short for Undershift). The Under is great because it typically guarantees that Stanford’s pass rusher par excellence Peter Kalambayi (B) can’t be double-teamed — Brennan Scarlett (E) gives him protection by occupying the only other lineman who would normally double-team Kalambayi. But Washington knows that Kalambayi will probably be attacking the backfield, making him an easy candidate for a trap play.

And the play goes off perfectly. It was like something out of Ocean’s Eleven.

At the snap, Kalambayi unsurprisingly surges forward, but Washington has already pulled out its right guard to block him, and as anybody who has been pushed sideways while running can tell you, Kalambayi has no leverage to withstand the block. He’s out of the play.

The left tackle, who would normally block Kalambayi, briefly helps the left guard block Scarlett and then heads straight for Blake Martinez (M). That ensures that Stanford’s best run defender is neutralized by an offensive lineman. He’s out of the play.

Despite the LT’s help, the left guard still ends up holding the daylights out of Brennan Scarlett (E) on the play. But that’s going to get flagged maybe 10 percent of the time. He’s out of the play too.

The only person left in the box that can do anything about the run is Kevin Palma (W), and after he hesitates for a moment before charging the running lane, the H-back (who also pulls across the formation) knocks him out of the play too.

Although I hate it when Stanford gets burned, I can’t help but admire it when a play runs like clockwork. The line and the playcall got Gaskin fifteen yards easily. Then Gaskin started trucking people. Stanford may have won this game and won it easily. But my goodness, Myles Gaskin is a freshman. Hide your wives. Hide your children. Myles Gaskin’s not going away.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.