Two weeks ago, Stanford softball did not hear its name called on Selection Sunday for the second consecutive season. After an NCAA tournament streak that lasted 16 years, this was more than just a crack in the facade. It was a sign of a crumbling foundation.

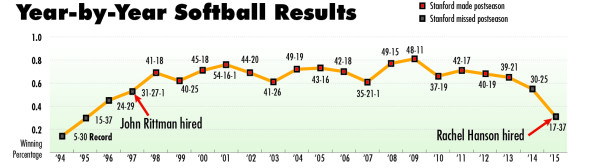

The collapse first became evident at the end of the 2014 season, when a faction of the team presented athletic director Bernard Muir with sweeping allegations against 18-year head coach John Rittman — allegations that have since been disputed by at least half of the team. A group of parents and former players supported those allegations, which also implicated Rittman’s assistants and the team’s trainers. Just 18 days after that contingent met with Muir, Rittman resigned.

Players who were not in that meeting with Muir have since contended that a thorough investigation was not conducted in response to the allegations, and that Rittman’s departure was forced.

The fallout from Rittman’s resignation has resulted in one of the worst seasons in program history, marred by infighting, the midseason departure of three seniors and questions surrounding Muir’s leadership.

The meeting with Muir

On May 12, 2014, a group of five parents and 10 players met with Muir. Six of the players had already left the team, graduated or finished their senior season, while the other four were eligible to return for the 2014-15 season.

These “anti-Rittman” players told Muir that five players who supported Rittman’s staff had not been invited to the meeting. They also said they had received permission to speak on behalf of the team’s five freshmen, who were not in attendance; however, most of the freshmen later felt that their views were misrepresented in the meeting with Muir. One of the freshmen said she only had concerns about the team’s trainers but supported the coaching staff, while players at the meeting made allegations against both.

The Daily reached out to all 10 players who attended the meeting with Muir. Each either declined to comment or did not reply to an interview request; Stanford Athletics’ media relations department declined comment on behalf of one player who they said had declined similar requests in the past.

However, 23 pages of notes that were typed by a parent at the meeting — and later distributed to the rest of the team — detail the group’s wide-ranging allegations against Rittman, his coaching staff and the team’s trainers.

The transcript included claims of two NCAA violations, mishandling of alcohol-related incidents, gossiping by assistant coaches, an inappropriate nickname for a player, favoritism, incompetent trainers and depression among players on the team. Players also alleged that trainer Brandon Marcello had made inappropriate comments, touched players’ legs and sides, showed favoritism toward those he found attractive and had an inappropriate relationship with a player.

The player in question called the claims against her “disgusting and untrue.” Marcello and Rittman both declined to comment for this story.

“I appreciate the opportunity to provide further comment,” Rittman, now an assistant coach at Kansas, said in a statement to The Daily, “but I would like to remain in the present and would be happy to talk about my role with the Kansas softball program.”

At the end of the meeting, Muir said that it was the first time he had heard most of the allegations. A parent said that information had previously been brought to Senior Associate Athletics Director Kevin Blue, who supervised the softball program. Both Muir and Blue declined to comment for this story.

On May 12 and May 14, 2014, Blue met with a total of five pro-Rittman players at their request. Though they were concerned that the other meeting was taking place, they did not know what had been alleged, so they said that they didn’t think it was necessary to meet with Muir at the time.

The players said that Blue asked them their thoughts on specific coaches and trainers, but would not say what claims had been made by the anti-Rittman group.

“We told him it was kind of hard to dispute things that we didn’t know were being said,” said then-junior Cassandra Roulund, one of the players who met with Blue.

According to the pro-Rittman players, Blue ended both meetings by assuring them that no rash decision was going to be made, while promising that the investigation would be thorough.

“We felt really reassured that what we did was going to be fine,” said then-junior Hanna Winter, “but we definitely were misled.”

In the 16 days between the second meeting with Blue and Rittman’s May 30, 2014 announcement to the team that he would resign, the pro-Rittman players said they only heard from administrators once more, in an email from Muir about players-only group therapy meetings with a professional counselor. The private meetings focused on group dynamics and favoritism — but not on other allegations that were made against Rittman — and their content was not shared with the administration.

The day that Rittman resigned, a parent who was in the May 12, 2014 meeting with Muir distributed the 23 pages of typed notes that he said covered “some of the things” from that initial session.

Pro-Rittman players were blindsided by most of the claims that had been made about Rittman, his assistant coaches and players who were not in the room. Winter said she had never heard from her teammates about many of the concerns they raised in the meeting with Muir; Roulund added that players were unfairly spoken for, and some of the attendees had told stories from when they weren’t even on the team. Roulund said she thought the meeting was “a witch hunt.”

“There were just little things that I think they were just trying to bring up to see if anything would work, anything would stick, anything would grab the attention of the AD in order to make the story better, or make change happen, or get Coach fired,” Roulund said. “A lot of these had nothing to do with Coach. They were just things that were brought up to try to make a story.”

Coaching changes

As a result of the allegations, Marcello became the subject of a Stanford-initiated Title IX investigation conducted by an outside attorney. The investigator interviewed 26 players, coaches and athletic staff. The player who was accused of having a relationship with Marcello was asked by the investigator if the relationship was sexual in nature; she said it was not.

“I don’t ever want to take away [from] how women feel about sexual harassment,” the accused player told The Daily. “As a woman, I respect that, and as a woman, I would stand up for women.

“But I was one of the women they used in these accusations, and I can tell you that it’s absolutely not true. And seeing the other side of that, and seeing the result, and the consequences of these false accusations, is just heinous, and horrendous, and it’s just unfair.”

On July 11, 2014, the investigator presented her findings to Stanford’s Title IX coordinator, Catherine Criswell, who sent a final decision letter to players on Aug. 6, 2014. The investigation found that it was more likely than not that Marcello “engaged in persistent unwelcome conduct that in the aggregate created a sexually hostile environment,” and that he “failed to maintain appropriate boundaries with several players.”

“While the inappropriate conduct may only have been directed at certain students and while some students may not have subjectively felt offended by this conduct,” the letter said, “this conduct nevertheless had the effect of creating a hostile environment based on sex for the softball team as a whole, thereby depriving students of the full benefits of and participation in the softball program.”

As a result, Marcello was removed from his position.

Criswell’s letter, which came more than two months after Rittman’s resignation, also cleared Rittman and his staff of wrongdoing related to the sexual harassment allegations. It said that the team would have new coaches and trainers for 2014-15 “for reasons unrelated to the Title IX case.” Stanford did not retain Rittman’s two assistant coaches.

Rittman has not publicly discussed why he suddenly left Stanford. In response to previous media requests, University administration has said it is legally required to keep personnel matters confidential.

Pro-Rittman players believe the longtime coach was pressured to leave. Roulund said that in the period between the meeting with Muir and Rittman’s departure, associate head coach Claire Sua-Amundson told her that she thought the administration was going to “clear house.” Sua-Amundson declined to comment for this story.

On April 9, 2015, a letter signed by 16 parents representing nine players was sent to University President John Hennessy and Provost John Etchemendy, claiming that “Muir’s failure to perform adequate due diligence led to Mr. Rittman’s forced resignation and the termination of his staff.” None of the nine players had participated in the meeting with Muir, and four of them were members of the freshman class that the anti-Rittman players had claimed to speak for.

Bettina Winter, Hanna’s mother and the author of the letter, told the Palo Alto Daily News that she “would like to see Bernard fired.”

She claimed that Muir has denied any connection between the meeting with players and parents and Rittman’s departure. However, in a response to Winter’s letter, Jeff Wachtel, a senior assistant to Hennessy, wrote, “We cannot comment on the details of the investigation. I can confirm for you that we conducted a thorough investigation and our best judgment was to make changes in the coaching staff.”

Yet Pro-Rittman players maintained that the investigation could not have been thorough if players who supported the coach were not interviewed about the allegations.

Roulund and Hanna Winter said they also believed that the fact Rittman resigned rather than was fired indicated little about the nature of that resignation.

“He cares so much about the girls, that if he was told people were unhappy, he was probably very easily pushed out,” Roulund said.

Still, Roulund and Winter argued, had administrators done a better job of verifying the allegations, the administration would have found discrepancies between the anti-Rittman claims and other players’ views. Roulund and Winter doubted that Rittman would have been pressured to resign had the athletic department recognized this.

A blank slate?

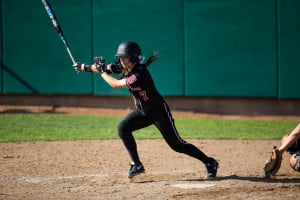

In 1997, Rittman had taken over the fledgling Cardinal program and transformed it into a perennial NCAA Tournament participant. Stanford had only missed postseason play twice in Rittman’s 18 years as head coach, in his first and last seasons. He had reached two Women’s College World Series and produced 16 All-Americans during his tenure.

Now Rittman was gone, and his replacement — former Dartmouth head coach Rachel Hanson — struggled to erase the team’s divisions. The program’s culture continued to deteriorate during her first season at Stanford, which ended with Roulund, Hanna Winter and another pro-Rittman rising senior, Leah White, quitting the team.

When she took over, Hanson had just led the Big Green to its first Ivy League title in program history. Her nine years of head coaching experience had been at Dartmouth and the University of Dallas, making Stanford her first head coaching stop in an elite softball conference.

Hanson’s step up was quickly complicated by the aftermath of the allegations made against the previous coaches and trainers. One of the players who participated in the meeting with Muir left the team; another player, freshman pitcher Carley Hoover, transferred to LSU. Asked by The Daily at the time, Hoover declined to elaborate on her decision to leave Stanford. But a year later, her father — who declined to comment for this story — was among those who signed Winter’s letter supporting Rittman.

Just as pressing as those departures was the rift in the team that had been created by the allegations against Rittman and his staff. Pro-Rittman players felt unfairly spoken for — and spoken of — by their teammates who had met with Muir. They said the accusations that one player was an alcoholic and that another had a relationship with Marcello were the most damaging.

In the meeting, a player claimed that when she reported an underage teammate who was allegedly under the influence of alcohol before a game, the teammate was not disciplined and the coaches told the reporting player that she shouldn’t have come forward. Anti-Rittman players claimed that the teammate — who was not in the room — had a drinking problem, and that it was an “outlet” for the issues with the coaches.

Pro-Rittman players, however, said that the player who may have been hung over before a game was in fact disciplined; they claimed she was sent home by the coaches that day and later had to apologize to the team. Though the player in question declined to comment for this story, pro-Rittman players insisted she did not have a drinking problem. (Her parents were among those who signed Bettina Winter’s letter in support of Rittman.) Pro-Rittman players also contended that the team’s seniors, not the coaches, decided that this issue should have been handled by the team and not by Rittman’s staff.

The anti-Rittman players’ allegations about Marcello’s relationship with a player also drove the two sides apart. In the anti-Rittman players’ meeting with Muir, they said that Marcello and the player would often get coffee and that she sometimes dropped food off at his house late at night. One meeting participant called their relationship “sickening” and said she thought the player was using the interactions to gain playing time.

The player in question described Marcello as a mentor and said she often talked with him about their shared interests, but that they were never alone together. The weekly coffee meetings were open to the whole team and typically included Marcello, the player in question and two of her teammates, according to several players. The meetings focused on future life plans — Marcello termed them “Beans and Being.” The player said she would sometimes accompany teammates to Marcello’s house to drop off donuts, a team-wide requirement he had instituted for players who showed up to lifting sessions late and which she saw as a mild alternative to running or harsher punishment.

The rising senior class was the group most polarized by the allegations, and Hanson — who declined to comment for this story — attempted to address this. According to Roulund, Winter and White, Hanson gave each senior three options late last fall: They could discuss what had happened, ignore the issues without letting them affect on-field performance or leave the program without a scholarship. All of the anti-Rittman seniors chose the first option, while all of the pro-Rittman seniors chose the second one.

After considering their responses, Hanson presented the choice again to both the juniors and the seniors, with two modifications. Ignoring what had happened was now off the table, she told them, but the players’ scholarships would be honored if they opted to leave the program. Faced with a decision between discussing the problems and quitting softball, every player chose the former, though Winter said she did so “begrudgingly.”

Roulund, White and Winter described the three resulting “feeling meetings” with upperclassmen right before the season, in which players could only make statements that concerned themselves and began with “I feel.” The meetings were moderated by Hanson, not a professional counselor, which Roulund, White and Winter said made them uncomfortable because of the content of the meeting with Muir. All three players felt that the meetings were ineffective in bringing the two sides together.

“It felt like the coaches were the judge and jury, and we were just trying to make our point to them,” Roulund said. “I don’t know if there was even a benefit coming out of it other than just trying to get the coaches on your side, because all of us returners knew why we were upset at each other.”

“If we were to have those meetings, it should have been done with a professional, not with [Hanson],” Winter added.

After the group therapy sessions arranged by Muir the previous May, multiple players said that athletic department administrators should have arranged similar sessions with a professional counselor.

Hanson had offered the returning players a blank slate, telling them she did not want to judge them on the past. But some pro-Rittman players struggled to move past what had happened to Rittman, and Roulund, White and Winter said that as a result, the new coaching staff began to gravitate toward the anti-Rittman group.

“Every time we were at the field it was a reminder of how it used to be, and how certain people on the team had fully betrayed us, and how they had ruined our family and what we had,” Winter said.

“We did seem like the outcast troublemakers from [the new coaches’] perspective, because we were unhappy,” Roulund said. “From the beginning, we just felt like we were treated like delinquents. Everything that we were doing, every mistake that we made, was seen like an act of defiance against the coaches, when it wasn’t.”

Several players said that Hanson’s lack of sympathy for the pro-Rittman players’ dissatisfaction contributed to a sense that the season was being used as a waste year to get rid of the seniors.

This was exemplified on the first weekend of the season, pro-Rittman players said, when Hanson made an example of White. Hanson instituted a new “family time” rule that strictly determined when players could interact with relatives. For the season-opening Kajikawa Classic in Tempe, Arizona — White is from nearby Phoenix — family interaction had been limited to the 15-minute walk from the game to the bus.

After the first leg of a doubleheader on Feb. 6, 2015, the Cardinal’s game against North Carolina was delayed for two hours. Some players passed the time by listening to music or checking their phones. White was hitting balls off a tee when her brother came up and started talking to her through a chain-link fence.

That’s when Hanson approached. “What do you think you’re doing?” she said. “I thought you were better than this.” Hanson went to talk to the other coaches, and Roulund heard Hanson tell them, “I don’t care whether we win this game or not. We’re going to learn a lesson tonight.”

White was benched against North Carolina, and despite apologizing to Hanson at breakfast the next day, she was held out of the team’s next two games.

As a junior, White had started every game, finished second on the team in batting average (.356) and ended the season on a 54-game errorless streak. She finished fourth or better on the team in batting average in each of her first three seasons, was twice named to the All-Pac-12 second team and earned three NFCA All-West Region second team selections.

Beginning with the Kajikawa Classic, however, White’s playing time dipped during her senior year. Before the confrontation in Tempe, White had started all but three of Stanford’s games over her first three seasons. In 2015, she started 33 out of 43 games before quitting the team. She said that being in and out of the lineup hurt her confidence and accounted for her drop in batting average to .264 (sixth-best on the team).

“You need to feel the confidence coming from your coaches,” White said. “You need to feel like they want you to do well, and I definitely did not get that this year, whatsoever.”

Ultimately, the family time policy became more lenient as the season went on, but several players said that it was not enforced consistently.

“I just feel like [White] was made an example of,” Winter said. “It was almost Coach Hanson’s way of being like, ‘If you defy me, this is what happens.’ First of all, it doesn’t make any sense to make yourself a leader in that way…and you also ruined a career just to prove dominance. That’s wrong.”

Roulund, White and Winter also felt unfairly targeted by a policy that involved new pitching coach Megan Langenfeld. Langenfeld — both a pitcher and a left-batting power hitter — had won the 2010 Women’s College World Series with UCLA, hitting over .700 and setting a WCWS record for slugging percentage (1.529) in the process. The three-time All-American also hit .527 her senior year and set the UCLA single-season record for slugging percentage (1.085). Roulund, White and Winter all batted left-handed as well, so they often asked for hitting help from Langenfeld instead of their right-handed hitting coach, Dorian Shaw.

A couple of weeks into the season, however, Langenfeld said she could no longer offer them pointers. When Roulund asked Hanson about this, Hanson said that players were only allowed to go to her or Shaw for hitting advice.

Once Roulund, White and Winter quit the team, Hanson abandoned this policy.

‘A shit year’

With the situation between the two sets of returning players unresolved and tensions between the coaches and some pro-Rittman players mounting, another group was caught in the crossfire: the freshmen.

Hanson mentioned to the younger players that the upperclassmen were dealing with issues, but multiple freshmen who spoke to The Daily on the condition of anonymity said they didn’t fully understand what was going on before the season. One freshman noticed that who she chose to socialize with was perceived as taking a stance on an issue she knew little about.

“You feel like every move you make is calculated,” she said. “Everyone’s watching.”

The freshmen were initially taken in by the anti-Rittman group, but those who spoke with The Daily said that most freshmen became closer with the pro-Rittman players after they learned what had happened the previous spring. One freshman said that for her, the turning point was seeing the notes from the initial meeting with Muir when anti-Rittman players made their allegations.

As the freshmen began to understand the team dynamic, they also noticed a cultural clash between the team and its new coach.

Several players considered Hanson controlling, with rules such as the family time policy and an 11 p.m. curfew on road trips that they felt demonstrated a lack of trust in players’ maturity. Policies like these had not existed under Rittman, the coach who recruited them a year earlier. The curfew forced players who were staying up late to finish their homework to go into the bathroom for light. Eventually, the team convinced Hanson to let them work in the lobby, but they were required to ask permission and say how late they would be there.

“We’re all adults in a hotel; we don’t have any means of leaving,” one freshman said. “She really tried to do everything that she could to show she could control us.”

In another instance, Hanson addressed the team after a game in which Roulund, Winter and others had asked teammates and coaches for pointers in the dugout. Hanson told her players that there were “energy suckers” (those who asked for help and took away teammates’ focus from the game) and “energy givers” (those who cheered), and that she expected them to be the latter.

Some players did not feel that Hanson embodied this standard herself. Early in the season, Hanson was overheard telling a trainer before a game that it would be “a shit year.” Before long, the entire team knew what had been said, and word got back to Hanson.

She addressed the team before the following day’s game, clarifying that she was referring to team culture and not talent. Hanson apologized that she had been overheard, but even when a player spoke up and argued that it should never have been said in the first place, Hanson insisted it was necessary in that moment. She also turned the incident back on her players, telling them to “grow up” and approach her sooner if they had concerns.

“You have to live by your own example,” one player said, referencing Hanson’s “energy sucker” policy.

Though the team was above .500 in nonconference play at the time that Hanson called the season “a shit year,” her phrase quickly became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Stanford was doomed by injuries to both of its pitchers that forced position players into the circle, but players said they lost motivation due to the program’s worsening culture and their growing dissatisfaction with Hanson. The team eventually lost 15 straight games over a month-long span and finished last in the Pac-12 with a 2-22 conference record. And despite returning all nine starters from a team that barely missed the NCAA tournament, Stanford’s team batting average dropped from .316 to .277.

Early in the season, players discussed a walkout to send a message to Muir, though this never panned out, as they were nervous that he would react by cutting the team’s funding or ending softball as a varsity sport. For Roulund, White and Winter, however, the program’s issues were too much to ignore during the team’s series against then-No. 1 Oregon.

Ducks head coach Mike White had once been a Stanford softball parent, but his daughter Nyree had left the Cardinal team for personal reasons midway through the 2014 season. Though Mike White was not present in the May 12, 2014 meeting with Muir, in the meeting a player referenced a letter that his family had sent alleging problems with the program and demanding change. And Roulund, Leah White and Winter claimed that during the “feeling meetings” in winter 2015, an anti-Rittman player had said that a member of the White family had asked her father to serve as their liaison during the meeting with Muir.

The father of the anti-Rittman player denied this to The Daily and declined additional comment; the anti-Rittman player did not respond to interview requests. When contacted through Oregon’s athletic communications office, Mike White did not respond.

After a surprisingly close 5-4 Oregon win in the first game of the series on April 18, 2015, the two teams lined up for the postgame high-five. When the three pro-Rittman players came to Mike White, they walked past him without saying a word or high-fiving him.

“I didn’t even want to be on the same field as Mike White,” Roulund said.

He turned back to the three players and began yelling. “Wow, classy!” he shouted, loud enough for both teams and parents in the stands to hear. “Grow up! Like I had anything to do with it!”

Mike White then confronted Hanson. “Good luck with your players,” he was overheard saying.

To Roulund, Leah White and Winter, Mike White’s response was somewhat validating.

“What coach would freak out that much from not getting a high-five from players?” Winter said. “That just goes to show, from our point of view, how guilty he is.”

The three players also thought that Hanson’s response was an overreaction. “What kind of shit was that?” she asked them. “Do you want to explain yourselves?”

The players told Hanson they felt uncomfortable high-fiving Mike White, and later apologized to her. They believed that she was aware of their concerns about Mike White’s involvement in the allegations against Rittman, as Hanson was present in the “feeling meeting” when this was discussed.

Hanson told the three players that they would be benched for the next day’s game.

Roulund, Leah White and Winter said they knew they had done something wrong, but they and other players said that they felt that the punishment didn’t fit the crime. For Winter, Hanson’s decision ended a 217-game start streak that she had built over three and a half years, beginning with the first game of her freshman season. Players believed that Hanson had chosen not to stand up for Roulund, Leah White and Winter, but rather to demonstrate to Mike White that they would be punished.

“That’s just the epitome of the season to me,” another player said.

The next day, Roulund, Leah White and Winter quit with three weeks left in the season.

The dust settles

The Cardinal finished the season 17-37, their worst record since 1995.

The week before the three players left the team, Bettina Winter sent the letter signed by 16 parents to Stanford President John Hennessy and Provost John Etchemendy.

“In essence, Mr. Muir allowed a small group of well-organized disgruntled parents, angry about the lack of playing time for their daughters, to take control of the leadership of the team,” the letter read. “This should not be the way Stanford handles its varsity teams. If it continues Stanford will not and should not continue to receive the high regard and respect it currently enjoys.”

“Had this been a men’s sport,” it continued, “the firing of the coaching staff would never have happened because these complaints consisted of vague uncomfortable sexual feelings (not involving the coaches), depression, lack of medical care (not in the coaching staff’s control) and general unhappiness especially over perceived favoritism. No group of people, however small or large, would have succeeded in unseating a highly reputable coach of a men’s sport with eighteen seasons on his resume. We believe that the handling of this matter demonstrates that Stanford is applying differing standards in the manner in which it treats men’s sports and women’s sports. As you know such differential treatment violates both the spirit and obligations of Title IX.”

The response sent by President Hennessy’s office to the letter provided little new information, though it claimed the administration would “work on a constructive course of action.”

“The atmosphere surrounding the Softball team over the last year has been very divisive, and this has been deeply troubling to many of us on campus including the athletic department leadership,” it said.

In May, Senior Associate Athletics Director Earl Koberlein — who now oversees softball instead of Blue — reached out to the three players who had quit to set up a meeting. Roulund thought it was a nice gesture, but called it “too little, too late.” The players said they have not yet responded.

It remains to be seen whether Hanson can repair the relationship with her returning players. One freshman said that she was “miserable” and felt she had compromised athletics for academics in coming to Stanford.

“When you don’t care about the game you’ve devoted your entire life to, something’s wrong,” she said.

Multiple players said they had considered transferring or quitting, and the freshman said that most of the team is unhappy. She claimed that some players are bound by money and others by their Stanford education, but that she already regretted her decision to join the Cardinal softball program.

“If there was a freshman coming here, if I could let them know not to come, I would,” she said.

Among players, confidence in Hanson’s ability to rebuild the program remains low after she presided over the team’s first sub-.500 season since Rittman took over in 1997. Those concerns extend to recruiting. The nation’s top pitching prospect, Kelly Barnhill, chose Florida over Stanford in October; another top pitcher in her class, Kelly Winegarner, had verbally committed to Stanford before Rittman left, but ended up playing for Northwestern.

“Honestly, I don’t think Coach Hanson is qualified enough to be coaching at this level,” one freshman said. “[She’s] in over her head.”

However, Roulund and Hanna Winter said they didn’t expect another coaching change this offseason. Winter said she thought that while Hanson had done more wrong than Rittman, she didn’t deserve to be fired, and that two coaching changes in as many years would make Stanford an unattractive landing spot for potential candidates.

Most of the players who were involved in the meeting with Muir or whose parents signed the letter have left the program, but the effects of the controversy remain.

“The sad thing is, a recruit is coming here in the hopes of elite athletics and prestigious academics,” one player said, “not knowing that they are about to sacrifice so much for so little.”

Contact Joseph Beyda at jbeyda ‘at’ stanford.edu.