An Istanbul program based on the curriculum of Stanford’s introductory programming methodology class, CS106A, will run for a second summer in a row to teach Turkish high school students how to code.

The program is directed by Asena Gencel MA ‘96, who works in software development, and her husband Nick McKeown, who has taught computer science and electrical engineering at Stanford for 20 years.

Gencel is an alumna of Darussafaka, a selective boarding school in Istanbul that only takes students who have lost one or both of their parents. Gencel and McKeown ran the program out of Darussafaka last summer, teaching 25 students over a two-week period, with the help of five section leaders.

This summer, they are partnering with Bosphorus University, which is in charge of selecting the 100 participating students from around Turkey and providing classroom space for the program. Eight Stanford section leaders will teach the program with the assistance of Turkish teachers.

Why Teach in Istanbul?

The primary purpose of this program is to give rising high school juniors, especially girls, their first experiences coding. This summer, they hope to achieve a 6:4 ratio of female to male students.

“Nick and I [had] talked a lot about doing something in Turkey to help education. We’ve always felt like girls need bigger voice in technology,” Gencel said. “We thought, can we do something in Turkey to help education, but also specifically to empower girls and women?”

Gencel and McKeown feel that the best platform for the program is in-person teaching, as opposed to using a Massive Online Open Course, or MOOC.

McKeown notes that MOOC participants “primarily include people who are strongly self-motivated, who already know it’s important for them to learn this material.” For this reason, Gencel recognizes that online teaching “doesn’t address the group of people who have no idea that they may actually have a talent for this, and these could be girls.”

Given the massive size of the software development industry and the United States’s industry dominance, McKeown sees the Istanbul program as a necessary endeavor. According to McKeown, there are 17 million people working in software development around the world, and a million new software jobs emerge every year, mostly in the United States.

“This represents a real problem for other countries,” McKeown said. “The question is: How do you go about fixing that, helping other countries. Because it can mean that sort of digital divide — a wealth divide — because the fastest growing area of any industry right now, any sizeable industry, is in software development.”

Beyond closing the digital divide, McKeown feels that it is an important time to push for computer science education in Turkey, considering the course of the current government.

“With the political change that’s going on in Turkey right now, and the general closing itself off from the outside world — becoming more conservative — [it’s important to create] a generation of young people who are in a job which is intimately connected with the outside world,” McKeown said.

Gencel and McKeown hope to see expansion around the program from within Turkey by training local instructors to teach the program. They anticipate that the program will eventually serve as a role model for teaching CS in other countries.

Applying CS106A

Stanford’s most popular class, Computer Science 106A: Programming Methodology, draws around 90 percent of Stanford students. In the fall quarter of 2014, 649 students were enrolled in the lecture.

“CS106A is now legendary in computer science departments across the world as the one that has been fine-Ttuned over 20 years or so by Professors Eric Roberts and Mehran Sahami,” McKeown explained. “That was the other ingredient. [We thought], ‘we’ve got this amazing class, we’ve got these amazing section leaders who have been trained and groomed, and selected.’ There must be a way to marry all of these things together to help Turkey.”

The Istanbul program is “another way of expanding that Stanford footprint for the benefit of others, as we all want to bring that expertise and help other countries to break that digital divide,” McKeown said.

The head teacher of the Istanbul program is Chris Piech BS, MA ’11, who is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in computer science at Stanford with a focus in machine learning for human learning. He has served as both a section leader and head teaching assistant for CS106A, and he accompanied Gencel and McKeown in the inaugural year of the Istanbul program.

“Our number one goal is motivation. If we can convince people this is something they see themselves doing, that would be a win for us…some of the drier details that aren’t necessary for a two-week course, we removed, and expanded on some of the more motivating, exciting parts of CS016A,” Piech said.

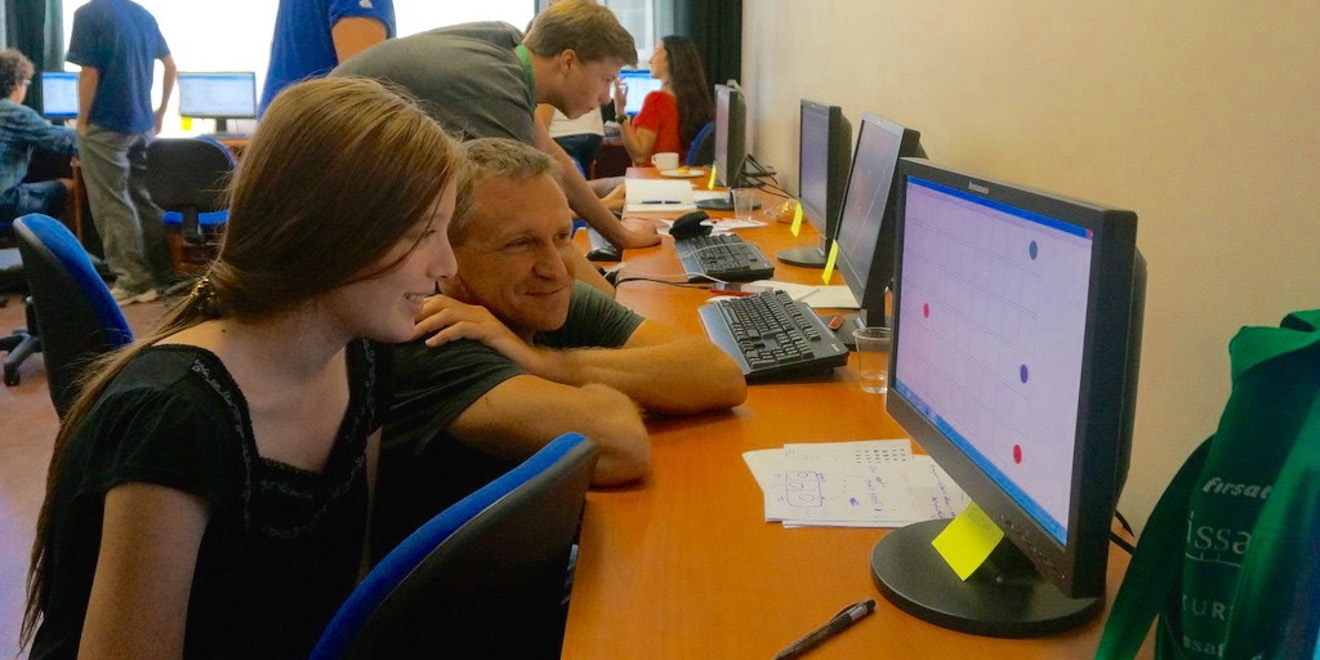

These changes to the structure of CS106A in application to the Istanbul program include an emphasis on hands-on programming in the classroom. The students typically sit through 10- to 15-minute lectures throughout the day, after which they immediately get to apply these concepts to coding while receiving individualized attention from the section leaders.

Section assignments are also designed to be more active and engaging. One assignment involves solving a scavenger hunt around the school while tracing code. Classic CS106A assignments, such as coding the video game Breakout without any starter code, still make an appearance. The final day and a half of the Istanbul program is dedicated to an individual project of each student’s choice that expresses his or her creativity. Last summer, a debate enthusiast created a political science geography quiz game.

Piech says that students who complete the Istanbul program could comfortably walk into week three of CS106A.

Contact Rebecca Aydin at raydin ‘at’ stanford.edu.