A Shakespearean tragedy about a Danish prince in an existential crisis, “Hamlet” has been re-imagined in many different contexts, but in Pigott Theater last weekend, Stanford TAPS proved yet again the timelessness of the struggles the play evokes. By placing heavy emphasis on the humanity of each character — their joys, moments of mirth, frustrations, and deep sorrows — guest director Rob Melrose and the rest of the company created a version of “Hamlet” with profound resonance.

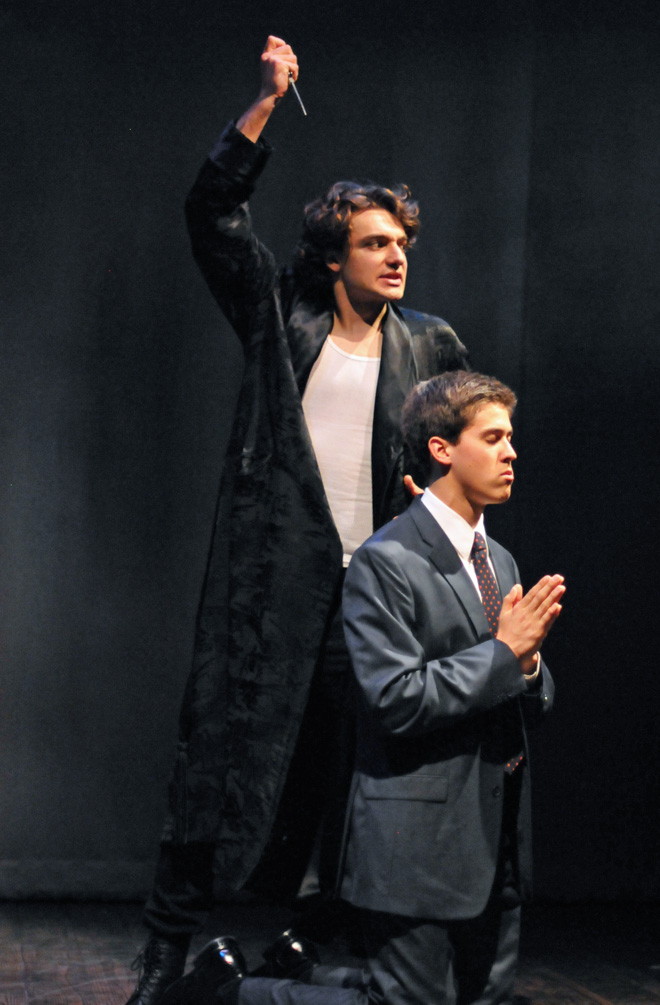

Andre Walker Amarotico ‘16 showed complexity and verve as the tortured Hamlet, oscillating between Hamlet’s extreme emotions and moods with ease. He could be acerbic and arrogant, but he showed great emotional range in portraying Hamlet’s inner conflict. Believing he had seen the Ghost of his late father (Ian Anstee ‘18), Hamlet battled suicidal desires while feeling viciously angry and revengeful toward his uncle Claudius (Louis McWilliams ‘16), whom he suspected of killing his father, the former king, so that he could marry Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude (Kiki Bagger ‘15).

The little details settled in the heart of the viewer. When Amarotico delivered the famous “to be or not to be” speech, questioning whether he should still be alive, he slowly ran a blade along his arm, a small action that heightened the tension of his dilemma. The actors had a great sense of pacing and spacing, and the fight scenes were raw and intense. In fact, the visceral struggle between Hamlet and the beautiful, troubled Ophelia (versatile actor Jessica Waldman ‘15), for whom Hamlet fights his own romantic feelings, was laid bare, in one way, by the fact that Waldman skinned her knee and drew blood.

The cast struck a perfect balance between the seriousness that the tragedy deserves and a lighter, more jesty tone that made the play more layered, impressive in that it is rare for a play to entwine humor so seamlessly while maintaining its identity as a tragedy. Moody, bass-heavy music and blue-outs in the lighting between scenes contributed to the overall somberness of the play, but there were also humorous moments, like when the convivial Polonius (Tylan Challenor ‘) gave sarcastic asides, or when Hamlet playfully did a handshake number with his friends Rosencrantz (Sebastian Sanchez-Luege ‘17) and Guildenstern (Noemi Ola Berkowitz ‘16). Later, when Berkowitz and Sanchez-Luege double as gravediggers, Sanchez-Luege generated a lot of laughs as he scooped skulls out of a hole in the stage. The combination of physical comedy and the actors’ playing up the ingrained wit in the script kept the play from becoming too heavy and made it feel more human, because life is never all pain or all joy, but an exciting combination of both.

The large stage (designed adeptly by Erik Flatmo) had two levels, which gave the actors a lot to work with, and they took full advantage of the set. At a given moment, some actors could be on the lower level and others above, unbeknownst to those below; or hiding behind curtains. This was most compelling when half-crazed Hamlet heard a noise and blindly stabbed his sword toward the curtain, instantly killing an eavesdropping Polonius. The dramatic irony of the audience knowing what the characters didn’t lent to the air of mystery and drama that made “Hamlet” so electric.

The main strength of this production of “Hamlet” was that the actors devoted themselves steadfastly to their roles, even when they played multiple characters —a common Shakespearean tradition. As an example, Anstee stood out in his powerful delivery of the Ghost, but also impressed as the Player King later on, distinguishing the characters with his physicality and vocal tone. His turn as the Ghost was haunted and troubled, but he became a confident King, standing tall. Those who stayed in constant characters were consistently powerful as well. The Shakespearean language was lucid because the actors showed in addition to telling. Director Melrose had the actors paraphrase each line at the beginning of the rehearsal process, so by the time of the production, the true meaning of the words was ingrained in the actors’ portrayals and interactions. Even Middle Age Denmark became a relatable world, highlighted by the fact that the costuming (by Connie Strayer) infused modern and period elements; Gertrude wore a queenly gown while the men sported sharp, contemporary-looking suits. This attests to the relatable quality of TAPS’ production in general, able to elevate the past into the present.

Contact Madeline MacLeod at mmacleod ‘at’ stanford.edu.