“At least I galloped — when did you?” says psychiatrist Martin Dysart in “Equus,” a unique play about a teen’s fanatical religious and sexual obsession with horses. As the play is highly experimental, The Freeks know it to be a risky one. Nonetheless, they charge ahead without fear of failure. While “Equus” showcases stellar direction and creative talent, it seems to fumble in packing a punch, ultimately leaving it at more of a canter than a gallop.

Before the play began, I had the opportunity to watch the cast prepare by engaging in energizers: they danced, jumped, and sent pulses of energy by squeezing each other’s hands. Director Yash Saraf ‘17 encouraged his performers to look each other in the eyes and connect in a powerful way. They do an excellent job of this; the way that the actors play off one another is vividly intense. This power drives the show forward.

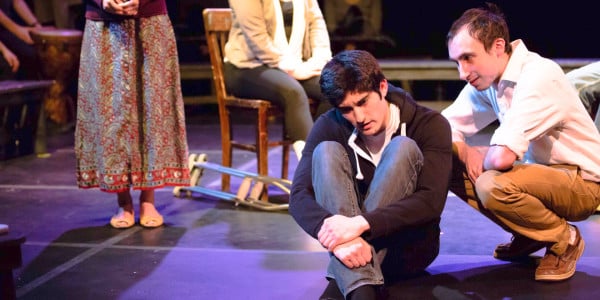

Alan Strang (Niko Varella ‘15) has committed an atrocity — blinding six horses with a metal spike. Varella, his dark eyes burning, shows versatility in his portrayal of the mentally disturbed character, shifting with ease between quiet, dark moments and unbridled fits of rage. It is up to Alan’s jaded psychiatrist, Dysart (a nuanced Jeffrey Abidor ‘15), to uncover the source of his psychosis. The flashback style that reveals Alan’s past effectively maintains an element of mystery.

Alan’s early experiences with riding horses sparked a deep affinity for their power and grace. His upbringing, marked by tension between his strict, atheistic father (a sharp Louis Lagalante ‘15) and deeply religious mother (Deanna Abrams ‘17 in a touching performance), led him to raise his objects of desire — horses — to a divine status. When sultry stable girl Jill (Sabelle Smythe ‘16) seduces Alan in the stables, he becomes consumed by the idea that the godly horses are watching him. In one of Varella’s most impacting moments, he screams at her to leave and blinds the horses, so that they can no longer see his sins.

In the seduction scene, both actors strip off their clothes and become nude. The staging — intimating an amorous relationship — makes this potentially uncomfortable moment feel organic.

A semicircle of performers with percussion instruments ring the actors, and the hits of the drums at strategic moments ramp up the tension and drama in the show, particularly in moments when parts of Alan’s past come to light. Having live percussion on the stage contributes to a tribal, pagan feel in tune with Alan’s idolization of horses.

The horses themselves are dancers in fascinating, abstract horse heads of wood and metal. This chorus paces and fidgets, giving little tilts of the head and outtakes of breath that are highly reminiscent of the true creatures. When Alan interacts with them, their rhythmic, circular dances — punctuated by the beating of drums — are beautiful to watch.

Despite all this, “Equus” struggles to find a consistent tone. The audience often finds itself inclined to chuckle, even at moments that should be serious, because Alan’s breakdowns can come across as comical instead of tragic. Likewise, Dysart seems more bemused than concerned most of the time. By the end, the audience was entertained but not haunted.

“Equus” has a fascinating storyline, and the impressive implementation of it on the Elliot Programming Center stage led to a worthwhile theater experience. Those involved with the production took risks, and — for the most part — these risks paid off. More shows at Stanford should emulate the audacity of “Equus.”

Contact Madeline MacLeod at mmacleod ‘at’ stanford.edu