Everybody knew the big storyline for No. 23 Stanford football’s Friday night game against Washington State. Could the Cardinal’s nation-leading defense corral a Cougar offense that had just set the all-time record for passing yardage in a game? As it turned out, the immovable object emerged victorious over the stoppable force. Even with passing game maven Mike Leach calling the plays for the Cougars, Stanford held Washington State in check. Repeatedly harassed by a powerful Stanford defensive front and forced to make short throws, Cougar quarterback Connor Halliday averaged a paltry 4.2 yards per attempt, and Washington State only managed 17 points, a far cry from its season average of 35. By the end of the game, the Cardinal had doubled the Cougars’ score, winning 34-17.

Stanford was only up by 10 points as WSU opened the second half, but they quickly set the tone for the rest of the game when junior linebacker Blake Martinez intercepted Halliday to end the Cougar drive. The play was a microcosm of the game: WSU’s Leach called his most well-known pass play, “Mesh,” but even though Leach’s scheme and Cougar execution got Halliday’s receivers open, heavy Stanford pressure forced Halliday into poor decisions that stalled WSU’s drives time and time again.

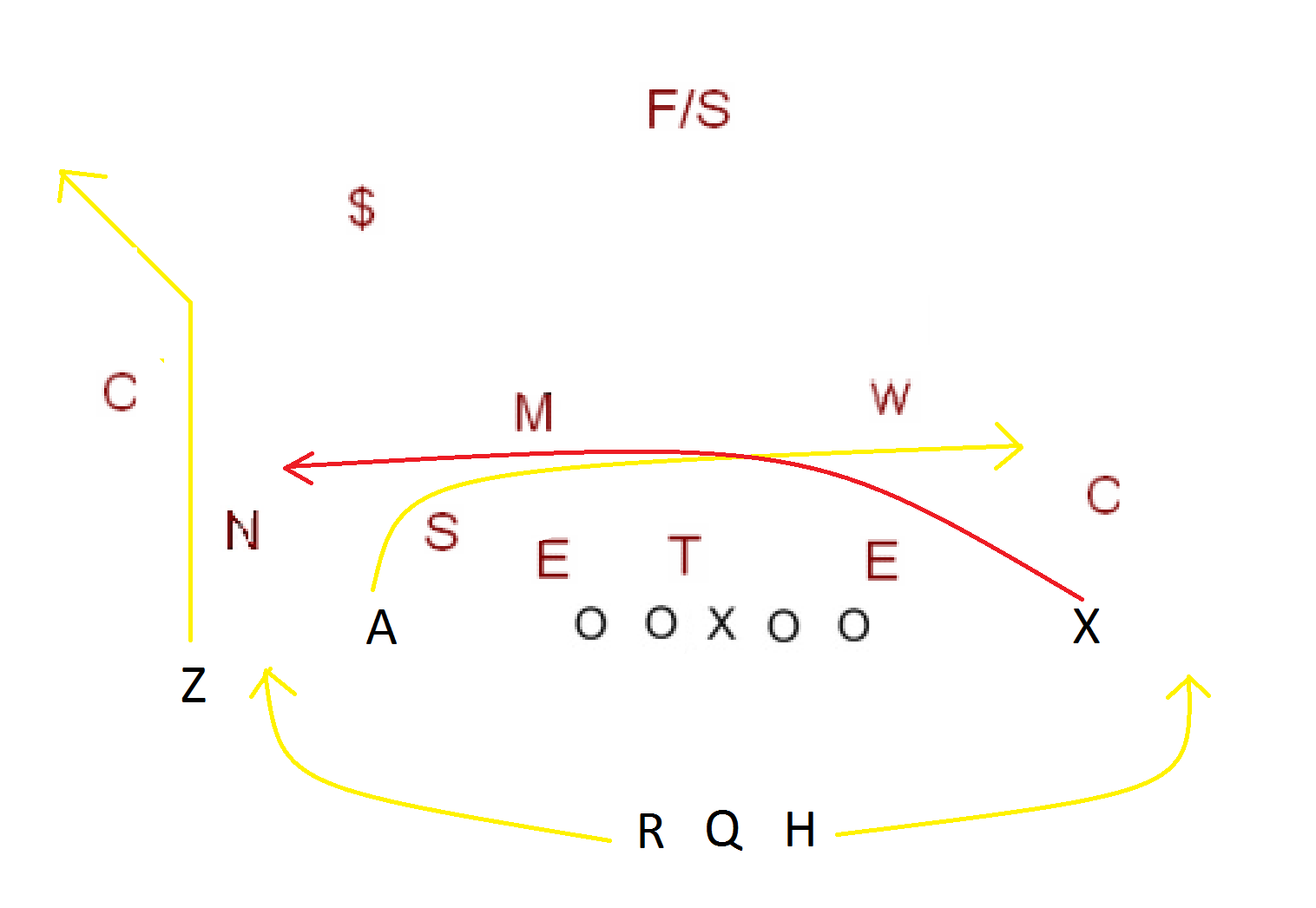

After completing a quick pass, Washington State found themselves facing second-and-6 at their own 29. “Mesh,” which features two shallow crossing routes (A and X) that effectively set screens for each other, is first and foremost supposed to be a ball-control play that shreds man defenses. Against a standard man defense, the crossing routes in Mesh will generate at least one open receiver, and on an easy route to boot. This was important because WSU’s offensive line could not give Halliday the time he needed to complete home run pass plays like “Four Verticals.” As such, facing second-and-not-short, Leach decided to prioritize moving the chains over going for the jugular.

Stanford defensive coordinator Lance Anderson called for zone coverage in response. Consistent with its defensive philosophy, Stanford played a conservative zone coverage for much of the game, and while zone coverage occasionally allowed the well-drilled WSU passing attack to complete throws in the coverage windows between the Stanford zones, it also put Stanford’s players in better position to gang tackle and limit WSU’s big plays. Zone coverage also took away room for Halliday to scramble, further choking off WSU’s run game.

The zone coverage did leave players open from time to time. On this play, WSU’s backside running back (H) had an opportunity against fairly soft zone coverage by Wayne Lyons (C). Moreover, Mesh’s crossing routes could still generate opportunities in the middle of the field against Stanford’s zone, albeit with a much smaller margin of error. WSU’s underneath receiver Isaiah Myers (X, red arrow) actually got open in the gap between linebackers Blake Martinez (M) and A.J. Tarpley (W).

Why didn’t they complete these throws? The answer is pass protection. On this play, Leach sent his running backs into pass routes instead of keeping them in the pocket to block Stanford’s pass rushers. With no backup plan, everything depended on line play. And even though Leach wasn’t calling slow-developing home run plays, Washington State’s offensive line could not keep Halliday’s jersey clean, even against a standard four-man pass rush (in this case, S, E, T and E).

Immediately under pressure from defensive tackle David Parry (T), who was dominant on Friday, Halliday tried to hit Myers’ underneath route (red arrow) and tossed an ugly pass off his back foot. He still could have connected with Myers, but he botched the timing, throwing the ball well in front of Myers – and under severe pressure, that is understandable. Sitting back in his zone, Martinez had an unobstructed look at Halliday and was in good position to make the interception.

Stanford’s defensive performance on Friday night made it clear: open receivers are one thing, but making these open receivers count is another animal entirely. WSU could still pass the ball – Halliday completed 42 of 69 attempts – but Halliday had no time to throw deep, and the Cougars were dependent on short passes, a strategy that left them with little margin for error. Halliday didn’t scramble once and, factoring in sacks, recorded 236 yards on 73 pass plays; taking out one 41-yard completion to Vince Mayle, the Cougars averaged 2.71 yards per pass play, a mind-bogglingly horrendous performance. To put things in perspective, Halliday was coming off a staggering 734-yard dissection of the Cal Bears, making the Stanford defense’s performance on Friday night all the more impressive.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.