When film critic Roger Ebert first spoke to director Steve James (“The Interrupters” and “Hoop Dreams”) about making a “bio-documentary,” he complained, in passing, about a sore hip. Days later, he was admitted to the hospital — his cancer was back. Unfortunately, Ebert would die five months later, before he had a chance to see James’ film. Fortunately, “Life Itself” is remarkable and a beautiful tribute to a life lived deeply.

Part memorial and part portrait, “Life Itself” tells the story of a prodigious mind, prolific writer and determined spirit. At the same time, the film is not blind to Ebert’s faults and vulnerabilities — they are, after all, what make him not only great, but also unmistakably human.

Ebert began his career as a newspaperman. At 15, he covered sports for his local paper. By his own account, he spent more time writing for the student paper than attending classes at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Life Itself” does a superb job of capturing the “unspeakably romantic” texture of Ebert’s formative years, intermingling family photographs, interviews with peers and excerpts from his early articles.

In 1966, Ebert began writing for the Chicago Sun-Timeswhile pursuing a Ph.D. in English at the University of Chicago. A year later, the Sun-Times’ film critic left, and Ebert got the job. He wrote reviews for the Sun-Times for 46 years, and he eventually won a Pulitzer Prize for his work.

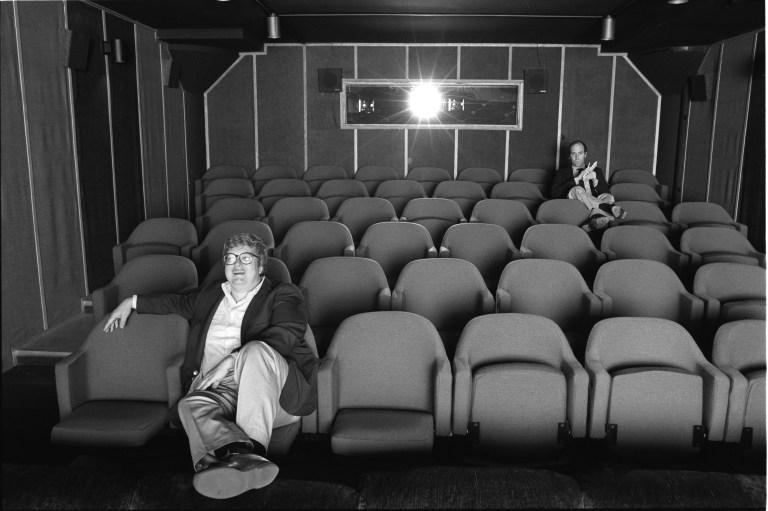

He went on to co-star on the television show, “Siskel and Ebert and The Movies,” with Gene Siskel, where they coined the famous “Two thumbs way up!” as a litmus test for the quality of new releases. Together, Siskel and Ebert became the most influential voices in American film criticism, starting conversations in households across the country. They used their influence to spotlight the work of young and upcoming directors like Martin Scorsese and Steve James. Errol Morris credits Siskel and Ebert with jumpstarting his entire career by giving “Gates of Heaven” a rave review.

In print, Ebert’s “clear, plain, Midwestern style” helped make his reviews accessible to a popular audience. He called his approach “relativist,” rather than absolute, because he sought to evaluate a film in terms of its prospective audience. When Siskel claimed that “Benji the Hunted” exhausted him, Roger shot back, “I don’t know, Gene. Your review is the typical sort of blasé, sophisticated, cynical review I would expect from an adult.”

Ebert never lost his wide-eyed appreciation for the magic of cinema. In his 2011 memoir, also titled “Life Itself,” Ebert wrote: “For me, the movies are like a machine that generates empathy. It lets you understand a little bit more about different hopes, aspirations, dreams and fears. It helps us to identify with the people who are sharing this journey with us.” Ebert made a career of loving and studying a film’s ability to unlock our imagination and spirit us away.

Despite his intellectual vitality and capacity for compassion, Ebert could also be juvenile, arrogant and dismissive of others’ opinions. “He is a nice guy,” commented one of his old drinking buddies, “but not that nice.” Even professionally, Ebert could be immature; the film includes outtakes from “Siskel and Ebert at the Movies,” in which Siskel and Ebert spar like adolescent boys, fighting tooth and nail over minutiae.

His friends also remember Ebert as something of a tortured soul, for whom alcohol was particularly dangerous: “He would walk home late at night after [binge-drinking] and he’d wish he was dead,” a former producer recalls in the film. All this was before Ebert joined AA, where he met his wife Chaz Ebert.

Chaz might be the source of light in Roger’s story. Much of “Life Itself” is shot in Ebert’s hospital room, where he spent most of the last few months of his life. In these scenes, Chaz is radiant — a constant source of both strength and tenderness. By all accounts, Ebert became a different person when he met her. She sparked kindness in him.

Moving interviews with Marlene Iglitzen, Siskel’s widow, reveal that Ebert’s relationship with Siskel also evolved. Despite or perhaps because of their combative on- and off-screen relationship, Siskel and Ebert loved each other. They shared a close friendship until Siskel died of brain cancer in 1999.

Any movie about “life itself” must contend, by necessity, with different definitions of love and the certain uncertainty of death. In this case, “Life Itself” documents Ebert’s decade-long battle with thyroid cancer, including a 2006 surgery that removed his lower jaw, which left him unable to speak, eat or drink. The film is unblinking in its portrayal of his treatment: We watch Ebert wince through physical therapy and struggle to walk on a treadmill. Scenes in which he is getting his feeding tube cleaned are some of the most difficult — and, perhaps, most important — to watch.

There is something refreshing about an intimate biographical film in which death is neither a silence nor a taboo. Even at the very end of his life, when conversation veered towards the macabre, Ebert’s eyes sparkled with warmth and good humor. “This is the third act,” he wrote, “and it is an experience.”

Alongside Ebert’s legacy of watching, writing and loving, “Life Itself” subverts any conception of death as “the end.” Thanks to Ebert himself, the effect of a good movie, like this one, is well-documented: When it’s over, the spell lives on.

Now playing at the Roxie cinema in San Francisco and available for rent on VOD.