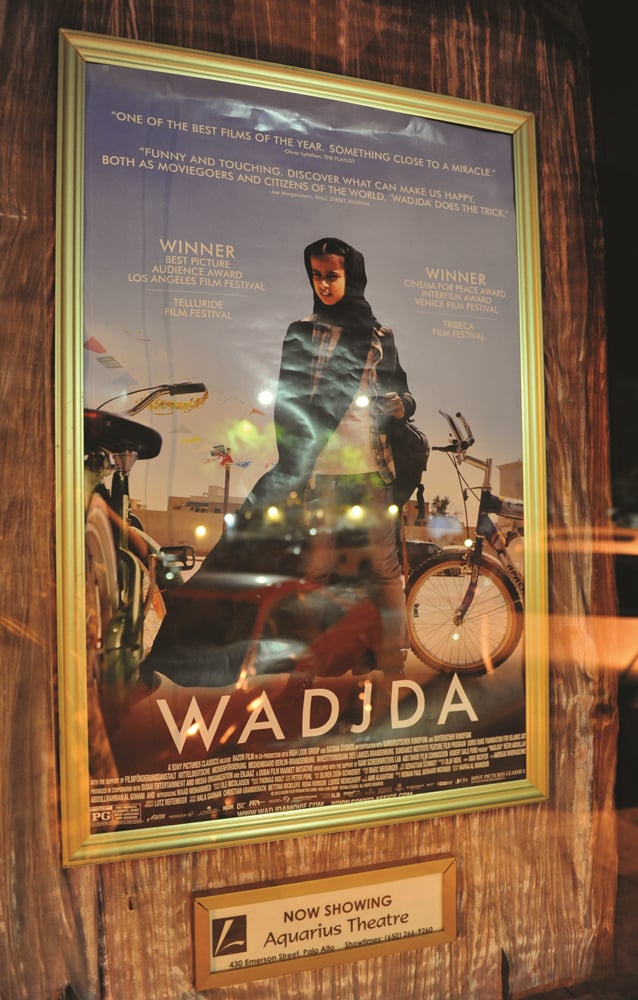

“Wadjda” is the first feature-length film both shot entirely in Saudi Arabia and directed by a Saudi woman — and Saudi Arabia’s first Oscar nomination for best foreign film.

The film is powerful because its heroine, Wadjda, is powerful: She is a clever, enterprising 10-year-old girl whose gumption cannot be contained by her burka (a full body cloak worn by Muslim women), her parents or her madrassa (school). She lives with her mother (Reem Abdullah) and mostly absentee father (Sultan Al Assaf) in a suburb outside Riyadh, the nation’s capital. There, she wears high-top Converse sneakers to school, listens to American pop music and sells bracelets illicitly. More than anything, Wadjda wants to buy a bike to race her closest friend, Abdullah (Abdullrahman Al Gohani).

When she sees a green bike strapped to the roof of a truck peeking out from behind a roadside wall, Wadjda follows it to a local toyshop. There, she discovers that bike costs 800 riyal, far outside her family’s price range. Despite her mother’s warnings that biking jeopardizes female fertility, Wadjda commits herself to various moneymaking schemes in order to purchase her bike. She sells mix tapes and agrees to carry notes between clandestine lovers.

The trope of the bicycle as a vehicle of freedom is by no means original, but maybe that’s part of the point. “Wadjda” inevitably recalls Vittorio Di Sica’s classic “The Bicycle Thief” and, more recently, the Dardenne brothers’ “The Kid With the Bike.” But in a country where women cannot drive — Wadjda’s mother depends on male drivers for everyday mobility — a bike is a particularly exciting emblem of autonomy.

In fact, as Wadjda attempts to define an identity in conversation with her parents’ values and expectations, her story reminds us that the turbulence of teenage years is universal. From her eye rolls delivered to her parents across the kitchen table to tearstains of frustrated self-expression, Wadjda’s vivid facial expressions are as imminently relatable as her teenage rebellion: She develops preferences for clothing, friends and hobbies contrary to her parent’s wishes.

Al Monsoura unveils the hypocrisies embedded in strict gender norms, critiquing conventional Western narratives about gender issues in the Middle East by showing that women are not passive victims in Saudi society. Wadjda’s school principal, for instance, comes closest to serving as the movie’s villain by enforcing a strict behavioral code in the school hallways and on the playground.

At the same time, she dresses in Western clothing, wears make-up and is even rumored to have a boyfriend. There are no easy male-female, oppressor-victim categories in this film; instead, women actively elaborate and challenge gender roles and religious doctrine.

In the film’s expansive beige-colored cityscapes, women move around anonymously, as silhouettes of themselves. In the intimate warmth of the kitchen and bedroom, on the other hand, Wadjda’s mother comes into her voice, singing songs while she prepares dinner or talking with friends on the phone. In one scene, Wadjda and her mother stand on the roof of their building. Below them, community political leaders and their all-male followers are gathering, epitomizing the consolidation of public decision-making authority among Saudi men. From their open-air sanctuary however, Wadjda and her mother are positioned to gaze back at the men from above.

“Wadjda” is a quietly affecting portrait of girl and society in the midst of transition. We sense the director’s own subtle subversion and unyielding hope for Saudi society. For 100 minutes, we see this optimism embodied in a mother-daughter embrace, a green bike and a young, hungry human spirit.

Contact Gillie Collins at gcollins ‘at’ stanford.edu.