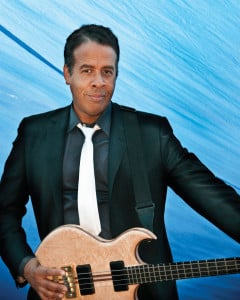

On Saturday, jazz bass legend Stanley Clarke will take the stage at Dinkelspiel Auditorium with his trio – comprised of pianist John Beasley and drummer Mike Mitchell – for what is sure to be one of the highlights of the Stanford Jazz Festival. In anticipation of the show, Intermission talked to Clarke about his upcoming performance, his approach to composition and the future of jazz.

Clarke, a Philadelphia native, entered the New York jazz scene in 1971, playing with greats like Art Blakey, Dexter Gordon and Joe Henderson and eventually forming the legendary “Return to Forever” group with Chick Corea. He is now a veteran performer, composer, conductor, arranger, producer and film score composer, with several recent Grammys to his name.

When Clarke was learning to play the bass, he explained, his “thoughts about music had pretty much crystallized. It was really just learning a craft but what was in my heart, musically, was already there: a love of great melodies”.

Clarke, who described composing music as “scoring your own life, your own feelings, wherever you’re at in that particular time,” singled out the piano as “the best writing tool that’s out there.”

“It reflects the orchestra with all the tones from the very lowest to the very highest, right in front of your eyes, unlike a saxophone or flute,” Clarke said. “Actually, you can hear a lot of them without even touching the keys.”

Asked about the future of jazz, Clarke expressed confidence in the style’s longevity.

“The concept of jazz dying is actually illogical because really good jazz music is just music that’s created by musicians that have virtuosic ability on their instruments,” Clarke said. “When you take the singers away, you’ve got a trumpet player who’s practiced the trumpet and he plays great. He’s not going to go play third trumpet in the Justin Timberlake band unless he has to, like to pay his mortgage…What he’s going to really want to do is what so many instrumentalists do: make instrumental records. And 99 percent of the time, those records are categorized as some form of jazz.”

“Jazz, to me, is an undefined term, because what you think is jazz might not be what the guy down the street thinks jazz is,” he elaborated. “It has morphed into many new kinds of things like smooth jazz, which is a combination of improvisation mixed with what I call R&B rhythm sections, like Kenny G music.”

Clarke sought, however, to avoid typecasting subgenres of jazz.

“[In all jazz] there is improvisation and the spirit of play, people playing together and soloing,” Clarke said.

Clarke argued that current music trends among young audiences largely exclude jazz.

“The music that’s disseminated to young people is not jazz,” he emphasized. “It’s pop music [or] rock music.”

However, Clarke identified greater popular awareness of jazz, noting that more people now know “that there are these figures like Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Louis Armstrong than they did 25 years ago.”

While that increased awareness may not translate into records sales, jazz has proven capable of reaching audiences through different mediums.

“[One of] the reasons people come out and see people like [him] is because of YouTube,” Clarke said. “Because they’ll see [him] and they’ll go, ‘I want to go see this guy live. I want to see if he really can do this.’”

Tickets to see the Stanley Clarke Trio at Dinkelspiel Auditorium on July 20 at 8 p.m. are still available and are priced at $15 for students.