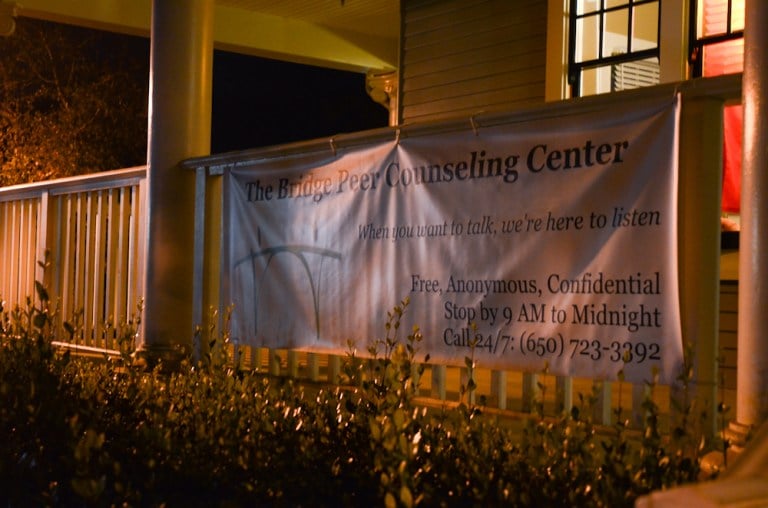

It’s 1 a.m. on Saturday morning. Half a block down, on Mayfield Avenue, the music at Sigma Chi is dying down, but at Rogers House, home of the Bridge Peer Counseling Center, the party’s just getting started.

Maria Mateen ’13, who has been a Bridge counselor for three years, sings softly as she rolls cookie dough in sugar — her fourth or fifth batch of the night. Strewn on the counter behind her are baking materials, dirty dishes, a laptop and a dozen bottles of spices and condiments. Altogether, the look is not one of a typical counseling clinic: That’s because The Bridge is also home to four student “live-ins” who man the 24-hour phone counseling service.

Mateen, the self-professed “mom of the house,” is the resident night owl.

“Can you help me find the cinnamon?” she asks me, hopping from the stove to the oven to back to the counter.

By 2:30 a.m., things begin to settle down. Most of the lights are off (Maria is still baking) and finally some calm is descending on the Bridge.

Not for long. The phone rings, and I hear the sound of shoes on stairs comes from the second floor. The house blinks back to life.

Live-in counselor Emma Pierson ’13 is on call tonight. Wrapped in a blanket in a small side room, she takes the call. It’s a serious one — a housing staff member calling on behalf of a resident, possibly one considering suicide. The door closes to give the caller confidentiality.

Meanwhile, Mateen’s head pops out from the kitchen doorway. “Want a cookie?” she asks.

For Mateen and Pierson, it’s just another day at the Bridge. They live at the center, their beds above the counseling center’s two main rooms for walk-in and phone counsels.

“We get mostly phone calls,” Pierson said. “It’s more convenient and more personal than having to come in and sit down.”

Normally there are more than a dozen trained peer counselors, manning the phones in the front room and counseling students in person. For calls that come in between midnight and 9 a.m., however, it’s up to the live-ins to face whatever problems arise.

“When the phone rings and you’re on call, I don’t think about getting to the phone, but I’m there,” Pierson said, comparing her thought process to the Pavlovian experiments that conditioned dogs so they would behave a certain way on command. “It’s probably not healthy.”

Even Pierson, a veteran of several dozen counseling calls, has trouble describing exactly what it’s like to counsel someone in the middle of the night.

“Talking to someone in the middle of the night when you’re just coming out of sleep is a pretty surreal experience,” she said. “It’s just you and this stranger, and they’re just confiding their intimate secrets to you. I feel very privileged, but it’s almost like being in a dream.”

It’s a dream that sometimes gives the counselors demons of their own. Providing round-the-clock emotional support for everybody who has their number — the Bridge has received calls from as far away as the East Coast –can stress counselors out too. They’re counseling mostly focuses on relationships and stress, but also about body image, sexuality and, occasionally, suicide.

“Some counselors will hang up [after a call] and cry,” Mateen said. “They’ve been there for the counselee, and when they hang up, they need to cry.”

It’s tough at times, but over the years, the Bridge has developed an internal support system of its own.

“The reason why you can support everyone is because everyone [at The Bridge] supports you,” Mateen said. “It’s never a drain on me because I have this amazing support system. … I never feel I’m fighting the battle alone.”

For day counselors like Alexandria Price ’14, that support system starts and ends with the live-ins.

“[Supporting day counselors] is something [the live-ins are] there for and really great at, especially if you’ve had a really tough call,” she said. “Anything you want, they’ll talk to you — about the call, reassure you, even counsel you.”

This week, Price was stuck with the midnight shift: Friday from 9 p.m. to midnight. While most students would lament the loss of half a weekend night, she emphasized how remarkable it is to work at the Bridge.

“With just three hours a week of time you can feel like ‘I really helped someone there,'” she said. “That’s a pretty amazing thing as a peer counselor, to have that kind of impact, to get someone the help they need.”

Most of the time, that help isn’t at the Bridge. Counselors don’t tell people how to solve their problems, oftentimes just talking through issues and listening. More serious problems are referred to Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), where students can get medical help.

“I’m supremely unqualified to tell people what psychologically to do,” Pierson said. “It’s a collaborative process.”

While they may not be doctors, Pierson and Mateen have unique opportunities to diagnose what troubles Stanford students, as they themselves experience the private insecurities and failures of a student body facing incredible pressures to succeed.

“It’s a part of the personality that we cultivate here, your Stanford personality,” Mateen said. “We’re always trying to perform the best we can, climb mountains, cure cancer. We’re so focused on our own successes and failures, it drives us apart.”

According to Pierson, this pressure might not only come from high-achieving peers, but from an internal drive as well.

“The kind of drive you need to get to a place like here does not always make you the most psychologically healthy person,” she said. “Almost always, the person you’re talking to is in pain, in some way.”

Sometimes, that pain leaves a mark on even the most experienced counselors, but the Bridge family has a way of propping each other up.

“There have been times when all four of the live-ins have been overwhelmed,” Pierson said. “When that’s true, you’re like, ‘I can’t take another call, can you take my call?’ It’s a web [of support].”

For the counselors at the Bridge, it’s all about expanding that web of support out of the house and making sure that no one feels alone in their struggles.

“The mission of the Bridge is to show people that you may be stressed, or sad, or broken, but you’re okay,” Mateen said.

As the clock ticks towards 3 a.m., Mateen takes her final batch of cookies out of the oven. They’re burnt and the bottoms stick to the sheet as she tries to scrape them onto a plate.

“It’s breaking,” I say as a cookie crumbles and splits onto the counter, the rest of it still stubbornly attached to the metal.

Mateen picks up the shard of sugar cookie and pops it in her mouth.

“It’s broken, but they’re still good.”